A Word is Worth a Bunch of Pictures…Sometimes

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Titan Books has embarked upon a Project. I use the capital “P” there because it’s a big, demanding, perhaps somewhat counter-intuitive Project: they’re converting graphic novels into prose novels or crafting prose novels based on characters born in a graphic medium.

The converse has, of course, been done on previous occasions and, to my mind, is an additive and, therefore, if not easier (no writing is easy) process than at least an additive one: graphic novels allow the writer to utilize color and object placement to set mood and facial expressions and body language, which studies have suggested are widely understood, as a shorthand, to enhance words with a second medium. Going the other way, from graphic novel to prose, however, feels, to this writer and reader, reductive, removing a tool and leaving the writer to flex far more muscles to tell a story that’s been told in more expansive fashion and thus, with a far more difficult job.

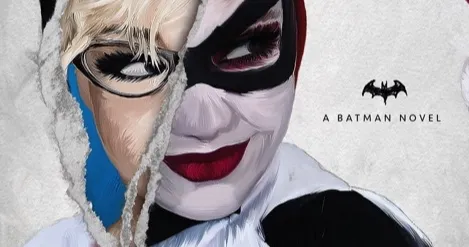

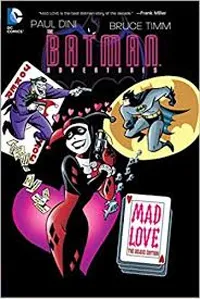

Having recently read Paul Dini and Pat Cadigan’s Harley Quinn: Mad Love and James R. Tuck’s Venom: Lethal Protector, both part of Titan’s graphic to prose line, my reader brain, conditioned both for comics and for prose, became fascinated with how such an operation was even possible. Cadigan was kind enough to take a few minutes to answer some questions about how she and Dini worked together to give Harley Quinn’s Mad Love arc a second life as a traditional novel (while keeping it a non-traditional story).

Book Riot: When a writer and an artist do a graphic novel version of a comic, they have the opportunity to add: art allows not only for color, panel breakdown, and object placement to establish mood and setting without the push-pull of show versus tell and word count restrictions, but also for the use of facial expression and body language which many studies suggest are, to some extent universal, to assist in telling the story (not that telling a stories in comics is easier, simply different). Novelizing a comic takes away those tools, tools that were programmed into the original telling, leaving the author with words alone, which seems like a much more difficult process. Is that the case? How do you go about the translation? How do you tell a story that was created with art without that art? Is the task more viable when the character as well established or does that not play in? How did you go about translating Mad Love specifically? Do you think the process would be different if you were working on a different story? A less well known one? Less “famous” characters?

Pat Cadigan: Well, I’m not a comics writer—I’m a prose novelist, so I’m used to painting pictures with words. When I’m writing one of my own novels, I’m describing what I see in my mind. Having the comic to work from meant I had actual pictures to refer to. But there was also quite a lot in Paul Dini’s outline that had not appeared in a comic. Harley Quinn: Mad Love includes a lot of material that was never part of a graphic novel. Paul’s outline was so clear that it wasn’t difficult to “see” what he was “seeing.”

Perhaps the process would be different with a different story—I know that whenever I write a novel, whether it’s one of my own originals or a novelisation or a media tie-in, I have to get acquainted with the story and the characters in a new way. I have to figure out how I can tell the story in the clearest, most vivid way, so that readers can “see” what’s going on. I’m a very visual person anyway—when I read a book, I’m actually watching a movie unfold in my mind. But as I said, I’ve never written comics so I don’t really know what it’s like to shift gears.

It probably would be a lot different to work with characters who weren’t as well known—I didn’t have to explain a lot of background for Gotham or Arkham Asylum. I didn’t have to explain who Batman is and what he does, and everyone knows what he looks like. But I did have to make sure I was true to the characters as they exist. Fortunately for me, that wasn’t hard—I grew up reading DC Comics and I’m very familiar with Batman and Gotham City. Also, when my son was little, we used to watch Batman: The Animated Series together so I was familiar with Harley Quinn, too. My son Rob and I got a kick out of her—she had a Brooklyn accent and my family is from Brooklyn. Of course, I had no idea at the time that years later, I would be collaborating with one of her co-creators on a novel about her!

Having recently read Paul Dini and Pat Cadigan’s Harley Quinn: Mad Love and James R. Tuck’s Venom: Lethal Protector, both part of Titan’s graphic to prose line, my reader brain, conditioned both for comics and for prose, became fascinated with how such an operation was even possible. Cadigan was kind enough to take a few minutes to answer some questions about how she and Dini worked together to give Harley Quinn’s Mad Love arc a second life as a traditional novel (while keeping it a non-traditional story).

Book Riot: When a writer and an artist do a graphic novel version of a comic, they have the opportunity to add: art allows not only for color, panel breakdown, and object placement to establish mood and setting without the push-pull of show versus tell and word count restrictions, but also for the use of facial expression and body language which many studies suggest are, to some extent universal, to assist in telling the story (not that telling a stories in comics is easier, simply different). Novelizing a comic takes away those tools, tools that were programmed into the original telling, leaving the author with words alone, which seems like a much more difficult process. Is that the case? How do you go about the translation? How do you tell a story that was created with art without that art? Is the task more viable when the character as well established or does that not play in? How did you go about translating Mad Love specifically? Do you think the process would be different if you were working on a different story? A less well known one? Less “famous” characters?

Pat Cadigan: Well, I’m not a comics writer—I’m a prose novelist, so I’m used to painting pictures with words. When I’m writing one of my own novels, I’m describing what I see in my mind. Having the comic to work from meant I had actual pictures to refer to. But there was also quite a lot in Paul Dini’s outline that had not appeared in a comic. Harley Quinn: Mad Love includes a lot of material that was never part of a graphic novel. Paul’s outline was so clear that it wasn’t difficult to “see” what he was “seeing.”

Perhaps the process would be different with a different story—I know that whenever I write a novel, whether it’s one of my own originals or a novelisation or a media tie-in, I have to get acquainted with the story and the characters in a new way. I have to figure out how I can tell the story in the clearest, most vivid way, so that readers can “see” what’s going on. I’m a very visual person anyway—when I read a book, I’m actually watching a movie unfold in my mind. But as I said, I’ve never written comics so I don’t really know what it’s like to shift gears.

It probably would be a lot different to work with characters who weren’t as well known—I didn’t have to explain a lot of background for Gotham or Arkham Asylum. I didn’t have to explain who Batman is and what he does, and everyone knows what he looks like. But I did have to make sure I was true to the characters as they exist. Fortunately for me, that wasn’t hard—I grew up reading DC Comics and I’m very familiar with Batman and Gotham City. Also, when my son was little, we used to watch Batman: The Animated Series together so I was familiar with Harley Quinn, too. My son Rob and I got a kick out of her—she had a Brooklyn accent and my family is from Brooklyn. Of course, I had no idea at the time that years later, I would be collaborating with one of her co-creators on a novel about her!

BR: Mad Love is a pivotal moment in the genesis of a beloved character about whom people have Very Strong Feelings. What is it like to step into a moment like that as as a writer? What are some of the exciting things about doing so? Is there anything you found particularly challenging about it?

PC: Although I was a DC Comics reader, I was never active in comics fandom so I wasn’t really aware of fan expectations. I knew there would be some fan reaction after the book came out but I was mainly focussed on the character and on Paul Dini’s outline. Paul’s vision was very clear and I wanted to be true to that.

The most challenging moment for me comes at what is the end of the comic Mad Love, when Harley Quinn is in Arkham, recovering from a seven-storey fall after the Joker throws her through a window. She’s trying to be strong and firm with herself, telling herself she’s done with the Joker for good, no more crazy, etc., and she suddenly spots the rose the Joker left for her with a get-well-soon note. Dr. Leland has just asked her how it feels to have devoted herself to a man who just threw her away and she says, “It feels like a kiss.”

I knew this was a nod to an old Rock’n’Roll song: “He Hit Me And It Felt Like A Kiss,” and Paul Dini has said as much. I didn’t want Harley to be a willing victim any more—a seven-storey fall is one hell of a wake-up call. But there are women who stay with their abusers because they are deeply in love with them. It’s hard to understand that when you’re looking at it from outside the relationship but it’s unrealistic to deny these women’s feelings. These women aren’t crazy but they’ve been isolated by their abusers so they no longer understand how unhealthy their situation is. Abusers keep their victims with them by giving them small doses of love and tenderness in between beatings—just enough to soften the victims’ resolve and decide to give the relationship another chance.

I didn’t “like” having Harley say, “It feels like a kiss.” No one I know thinks a seven-storey fall would feel like a kiss—I certainly don’t! But Harley was isolated and under the Joker’s control for a long time. It’s not so unrealistic to think that a sudden “loving” gesture from the Joker would suddenly make her all misty-eyed. But as it turns out it’s only temporary; she doesn’t return to the Joker immediately, which gives her the time and space to shake off his influence.

BR: What was the team dynamic like between you and Paul Dini? Did you know one another prior to the project? How often did you consult with one another? Was he more involved in the planning stages or did he also have a hand in the writing? What was it like to play in his sandbox?

PC: I’ve done novelisations and media tie-ins before, and I’m an old assignment writer from way back—I wrote greeting cards for Hallmark for ten years. So I’m comfortable with working with other people’s material. Paul Dini and I had never met; we communicated through our editor, Steve Saffel, which I think was the best way to do things. When I had questions, I contacted Steve. Steve contacted Paul, Paul gave him the answers, and Steve sent them to me. Doing things this way meant no one was out of the loop and everybody involved knew where everyone else was.

BR: There are a lot of Opinions and Feelings in the fandom about the relationship between Harley and the Joker. What’s your take as a writer? As a woman?

BR: Mad Love is a pivotal moment in the genesis of a beloved character about whom people have Very Strong Feelings. What is it like to step into a moment like that as as a writer? What are some of the exciting things about doing so? Is there anything you found particularly challenging about it?

PC: Although I was a DC Comics reader, I was never active in comics fandom so I wasn’t really aware of fan expectations. I knew there would be some fan reaction after the book came out but I was mainly focussed on the character and on Paul Dini’s outline. Paul’s vision was very clear and I wanted to be true to that.

The most challenging moment for me comes at what is the end of the comic Mad Love, when Harley Quinn is in Arkham, recovering from a seven-storey fall after the Joker throws her through a window. She’s trying to be strong and firm with herself, telling herself she’s done with the Joker for good, no more crazy, etc., and she suddenly spots the rose the Joker left for her with a get-well-soon note. Dr. Leland has just asked her how it feels to have devoted herself to a man who just threw her away and she says, “It feels like a kiss.”

I knew this was a nod to an old Rock’n’Roll song: “He Hit Me And It Felt Like A Kiss,” and Paul Dini has said as much. I didn’t want Harley to be a willing victim any more—a seven-storey fall is one hell of a wake-up call. But there are women who stay with their abusers because they are deeply in love with them. It’s hard to understand that when you’re looking at it from outside the relationship but it’s unrealistic to deny these women’s feelings. These women aren’t crazy but they’ve been isolated by their abusers so they no longer understand how unhealthy their situation is. Abusers keep their victims with them by giving them small doses of love and tenderness in between beatings—just enough to soften the victims’ resolve and decide to give the relationship another chance.

I didn’t “like” having Harley say, “It feels like a kiss.” No one I know thinks a seven-storey fall would feel like a kiss—I certainly don’t! But Harley was isolated and under the Joker’s control for a long time. It’s not so unrealistic to think that a sudden “loving” gesture from the Joker would suddenly make her all misty-eyed. But as it turns out it’s only temporary; she doesn’t return to the Joker immediately, which gives her the time and space to shake off his influence.

BR: What was the team dynamic like between you and Paul Dini? Did you know one another prior to the project? How often did you consult with one another? Was he more involved in the planning stages or did he also have a hand in the writing? What was it like to play in his sandbox?

PC: I’ve done novelisations and media tie-ins before, and I’m an old assignment writer from way back—I wrote greeting cards for Hallmark for ten years. So I’m comfortable with working with other people’s material. Paul Dini and I had never met; we communicated through our editor, Steve Saffel, which I think was the best way to do things. When I had questions, I contacted Steve. Steve contacted Paul, Paul gave him the answers, and Steve sent them to me. Doing things this way meant no one was out of the loop and everybody involved knew where everyone else was.

BR: There are a lot of Opinions and Feelings in the fandom about the relationship between Harley and the Joker. What’s your take as a writer? As a woman?

PC: I come from a rough background. My mother had the good sense to get both of us out of a very bad situation when I was young. But we weren’t well off; in our neighbourhood, it wasn’t Saturday night if the police weren’t called to someone’s house. We lived in an apartment building and I can remember my mother leaning out the kitchen window waving a broom and yelling at the man downstairs that if he didn’t stop hitting his wife, she’d come down there and shove the broom up his, er, nose. So yeah, I have some strong feelings about abusive relationships. I wasn’t comfortable writing about one. But it’s not something to ignore. The people who get into these relationships—and stay in them—aren’t stupid. I’ve known a number of highly intelligent women, capable in their careers, who have been drawn into relationships with people who aren’t worth the salt in their tears, to phrase a coin. Being strong and intelligent doesn’t mean you always make good choices.

Harley Quinn is a particularly complicated character because she’s actually supposed to be a villain. You’re not supposed to root for a villain…are you? Or are you? Harley sparks strong feelings in many fans—and not only female ones—because, villain or not, they don’t want her to submit to the Joker, who gleefully abuses her. On the other hand, just because she rejects the Joker doesn’t mean she’ll straighten up and become a white hat. She may break free of her abuser and still be a villain. She’s complicated; she confounds expectations. I love that in a character.

BR: How much research did you do on the characters and the backstory before you started writing? Did you read the graphic novel? Watch any specific episodes of the animated series? Any non-fiction research?

PC: As I said earlier, I was a DC Comics fan from childhood. I haven’t been reading comics much lately but I did read the comic Mad Love after I got the assignment. But also as I said earlier, I was familiar with Harley Quinn because I used to watch Batman: the Animated Series with my son when he was little. It was on every morning before school. We’d watch it together and then I’d walk him to school. (In case any parents are wondering how letting my kid watch TV before school affected him: he has a Master’s Degree in Japanese Cultural Studies and he works as an administrator for the London College Hospital medical school.) Of course, I rewatched the series and the Harley Quinn episodes in particular so I could re-familiarise myself with the character. Mostly, however, it was Paul Dini’s outline; his vision of Harley Quinn was perfectly clear.

BR: Why do you think Mad Love is an important story to tell or to continue to tell?

Personally, I think Mad Love is a brilliant take on a difficult subject—a smart, capable, beautiful woman taken in by a grotesque, insane, and abusive villain. Harley Quinn is complex, a strong woman with weaknesses. Most strong, intelligent women in any medium are portrayed as geniuses who always make the right choices. I know a lot of strong, intelligent women but they don’t always get everything right.

BR: Prior to Mad Love, most of your novels and stories have shaded toward sci-fi with the majority being more specifically in the realms of techno- and cyberpunk. You’ve also done some horror and written in the shared Battle Angel Alita and Wild Card universes. How did your previous work inform your take on Harley’s story? On the setting of Arkham? On the mythos of Gotham?

PC: Well, to be honest, besides Paul Dini’s brilliantly clear outline, I think I was most influenced by the TV series Gotham. I absolutely love how Gotham City is portrayed. And Arkham Asylum has figured prominently in many episodes, so I could get a clear image of what a grotesque place it was and so understand how Dr. Leland is struggling to make it more like a hospital and less like an inner circle of Hell. Of course, Harley Quinn doesn’t appear, although Catwoman and Poison Ivy do. They’re very young, not the seasoned criminals they become later.

As I said earlier, I’m a very visual person, so watching Gotham helped me see Gotham City from both the inside and the outside. When you’re *in* Gotham City, crazy costumed villains and a vigilante dressed like a bat become normalised. Coming in from the outside is something else. If you’re a villain like a mob boss, these are just things you can use to your advantage. But to a civilian—particularly a mental health professional—the crazy seems so thick you can cut it with a knife. Having Harley see Batman as a police-approved criminal rather than a hero and protector helped to build up her already existing problems with authority.

(Incidentally, I watch Arrow, Legends of Tomorrow, and The Flash, too. There’s a wonderful, albeit very brief, moment in Arrow when Amanda Waller is talking to Oliver Queen and John Diggle (I think) in the area where they keep prisoners locked up, and you hear a high, female voice call out, “Hey, does someone need therapy? I’m a licensed therapist!” And Amanda Waller bangs on the door to make her shut up. Nobody says so but I know that’s Harley Quinn. It gave me a chuckle.)

Of course, none of this answers your question as to how my previous work informed my take on Harley Quinn’s story. I’m not sure I can give you an answer to that. I had such a good time writing Harley Quinn: Mad Love and I think that above all informed my work. I enjoyed it from beginning to end.

BR: I really enjoyed your take on Batman—he seemed very much the sly, dry wit we all loved so much on the B:TAS. How did you capture that very specific Batman in prose? How did your previous work prepare you for that (monumental) task? How did it feel to join the pantheon of writers who have had the opportunity to craft the Bat, even in small snippets (because, let’s face it, who among us hasn’t wanted the chance)?

PC: I come from a rough background. My mother had the good sense to get both of us out of a very bad situation when I was young. But we weren’t well off; in our neighbourhood, it wasn’t Saturday night if the police weren’t called to someone’s house. We lived in an apartment building and I can remember my mother leaning out the kitchen window waving a broom and yelling at the man downstairs that if he didn’t stop hitting his wife, she’d come down there and shove the broom up his, er, nose. So yeah, I have some strong feelings about abusive relationships. I wasn’t comfortable writing about one. But it’s not something to ignore. The people who get into these relationships—and stay in them—aren’t stupid. I’ve known a number of highly intelligent women, capable in their careers, who have been drawn into relationships with people who aren’t worth the salt in their tears, to phrase a coin. Being strong and intelligent doesn’t mean you always make good choices.

Harley Quinn is a particularly complicated character because she’s actually supposed to be a villain. You’re not supposed to root for a villain…are you? Or are you? Harley sparks strong feelings in many fans—and not only female ones—because, villain or not, they don’t want her to submit to the Joker, who gleefully abuses her. On the other hand, just because she rejects the Joker doesn’t mean she’ll straighten up and become a white hat. She may break free of her abuser and still be a villain. She’s complicated; she confounds expectations. I love that in a character.

BR: How much research did you do on the characters and the backstory before you started writing? Did you read the graphic novel? Watch any specific episodes of the animated series? Any non-fiction research?

PC: As I said earlier, I was a DC Comics fan from childhood. I haven’t been reading comics much lately but I did read the comic Mad Love after I got the assignment. But also as I said earlier, I was familiar with Harley Quinn because I used to watch Batman: the Animated Series with my son when he was little. It was on every morning before school. We’d watch it together and then I’d walk him to school. (In case any parents are wondering how letting my kid watch TV before school affected him: he has a Master’s Degree in Japanese Cultural Studies and he works as an administrator for the London College Hospital medical school.) Of course, I rewatched the series and the Harley Quinn episodes in particular so I could re-familiarise myself with the character. Mostly, however, it was Paul Dini’s outline; his vision of Harley Quinn was perfectly clear.

BR: Why do you think Mad Love is an important story to tell or to continue to tell?

Personally, I think Mad Love is a brilliant take on a difficult subject—a smart, capable, beautiful woman taken in by a grotesque, insane, and abusive villain. Harley Quinn is complex, a strong woman with weaknesses. Most strong, intelligent women in any medium are portrayed as geniuses who always make the right choices. I know a lot of strong, intelligent women but they don’t always get everything right.

BR: Prior to Mad Love, most of your novels and stories have shaded toward sci-fi with the majority being more specifically in the realms of techno- and cyberpunk. You’ve also done some horror and written in the shared Battle Angel Alita and Wild Card universes. How did your previous work inform your take on Harley’s story? On the setting of Arkham? On the mythos of Gotham?

PC: Well, to be honest, besides Paul Dini’s brilliantly clear outline, I think I was most influenced by the TV series Gotham. I absolutely love how Gotham City is portrayed. And Arkham Asylum has figured prominently in many episodes, so I could get a clear image of what a grotesque place it was and so understand how Dr. Leland is struggling to make it more like a hospital and less like an inner circle of Hell. Of course, Harley Quinn doesn’t appear, although Catwoman and Poison Ivy do. They’re very young, not the seasoned criminals they become later.

As I said earlier, I’m a very visual person, so watching Gotham helped me see Gotham City from both the inside and the outside. When you’re *in* Gotham City, crazy costumed villains and a vigilante dressed like a bat become normalised. Coming in from the outside is something else. If you’re a villain like a mob boss, these are just things you can use to your advantage. But to a civilian—particularly a mental health professional—the crazy seems so thick you can cut it with a knife. Having Harley see Batman as a police-approved criminal rather than a hero and protector helped to build up her already existing problems with authority.

(Incidentally, I watch Arrow, Legends of Tomorrow, and The Flash, too. There’s a wonderful, albeit very brief, moment in Arrow when Amanda Waller is talking to Oliver Queen and John Diggle (I think) in the area where they keep prisoners locked up, and you hear a high, female voice call out, “Hey, does someone need therapy? I’m a licensed therapist!” And Amanda Waller bangs on the door to make her shut up. Nobody says so but I know that’s Harley Quinn. It gave me a chuckle.)

Of course, none of this answers your question as to how my previous work informed my take on Harley Quinn’s story. I’m not sure I can give you an answer to that. I had such a good time writing Harley Quinn: Mad Love and I think that above all informed my work. I enjoyed it from beginning to end.

BR: I really enjoyed your take on Batman—he seemed very much the sly, dry wit we all loved so much on the B:TAS. How did you capture that very specific Batman in prose? How did your previous work prepare you for that (monumental) task? How did it feel to join the pantheon of writers who have had the opportunity to craft the Bat, even in small snippets (because, let’s face it, who among us hasn’t wanted the chance)?

PC: Actually, Harley was my main focus. Perhaps because I knew her from B:TAS, I unconsciously modelled Batman from the series as well, although mostly I took him as is from the graphic novel Mad Love, which was what Paul Dini wanted. But I have to say that I wasn’t thinking of writing Batman as a monumental task while the work was in progress. I just wanted to get the character right—in particular, to make it clear that he wasn’t the demonised bad guy Harley Quinn had made him out to be.

BR: What are you working on now?

PC: I’d tell you but then I’d have to kill you.

Just kidding. I’m doing some short fiction and working on a novel that jumps off from the end of the novelette I won a Hugo for back in 2013. The novelette was “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out For Sushi.” Working title of the novel: See You When You Get There.

BR: What are you reading now?

PC: Lately I’ve been reading a lot of research for the novel I’m working on—books on quantum mechanics, string theory, the Tarot, and the I Ching, although I did take a few moments to read Stephen King’s two latest: The Outsider and Elevation.

PC: Actually, Harley was my main focus. Perhaps because I knew her from B:TAS, I unconsciously modelled Batman from the series as well, although mostly I took him as is from the graphic novel Mad Love, which was what Paul Dini wanted. But I have to say that I wasn’t thinking of writing Batman as a monumental task while the work was in progress. I just wanted to get the character right—in particular, to make it clear that he wasn’t the demonised bad guy Harley Quinn had made him out to be.

BR: What are you working on now?

PC: I’d tell you but then I’d have to kill you.

Just kidding. I’m doing some short fiction and working on a novel that jumps off from the end of the novelette I won a Hugo for back in 2013. The novelette was “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out For Sushi.” Working title of the novel: See You When You Get There.

BR: What are you reading now?

PC: Lately I’ve been reading a lot of research for the novel I’m working on—books on quantum mechanics, string theory, the Tarot, and the I Ching, although I did take a few moments to read Stephen King’s two latest: The Outsider and Elevation.

Other novels included in the Titan Project: The Killing Joke (September 2018), The Court of Owls (February 2019), Deadpool: PAWS (April 2018), Civil War (April 2018), Ant Man: Natural Enemy (July 2018), Spider-Man: Forever Young (October 2018), Spider-Man: Hostile Takeover (August 2018), Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World (April 2018), Who is Black Panther (April 2018), and Captain Marvel: Liberation Run (February 2019).

Having recently read Paul Dini and Pat Cadigan’s Harley Quinn: Mad Love and James R. Tuck’s Venom: Lethal Protector, both part of Titan’s graphic to prose line, my reader brain, conditioned both for comics and for prose, became fascinated with how such an operation was even possible. Cadigan was kind enough to take a few minutes to answer some questions about how she and Dini worked together to give Harley Quinn’s Mad Love arc a second life as a traditional novel (while keeping it a non-traditional story).

Book Riot: When a writer and an artist do a graphic novel version of a comic, they have the opportunity to add: art allows not only for color, panel breakdown, and object placement to establish mood and setting without the push-pull of show versus tell and word count restrictions, but also for the use of facial expression and body language which many studies suggest are, to some extent universal, to assist in telling the story (not that telling a stories in comics is easier, simply different). Novelizing a comic takes away those tools, tools that were programmed into the original telling, leaving the author with words alone, which seems like a much more difficult process. Is that the case? How do you go about the translation? How do you tell a story that was created with art without that art? Is the task more viable when the character as well established or does that not play in? How did you go about translating Mad Love specifically? Do you think the process would be different if you were working on a different story? A less well known one? Less “famous” characters?

Pat Cadigan: Well, I’m not a comics writer—I’m a prose novelist, so I’m used to painting pictures with words. When I’m writing one of my own novels, I’m describing what I see in my mind. Having the comic to work from meant I had actual pictures to refer to. But there was also quite a lot in Paul Dini’s outline that had not appeared in a comic. Harley Quinn: Mad Love includes a lot of material that was never part of a graphic novel. Paul’s outline was so clear that it wasn’t difficult to “see” what he was “seeing.”

Perhaps the process would be different with a different story—I know that whenever I write a novel, whether it’s one of my own originals or a novelisation or a media tie-in, I have to get acquainted with the story and the characters in a new way. I have to figure out how I can tell the story in the clearest, most vivid way, so that readers can “see” what’s going on. I’m a very visual person anyway—when I read a book, I’m actually watching a movie unfold in my mind. But as I said, I’ve never written comics so I don’t really know what it’s like to shift gears.

It probably would be a lot different to work with characters who weren’t as well known—I didn’t have to explain a lot of background for Gotham or Arkham Asylum. I didn’t have to explain who Batman is and what he does, and everyone knows what he looks like. But I did have to make sure I was true to the characters as they exist. Fortunately for me, that wasn’t hard—I grew up reading DC Comics and I’m very familiar with Batman and Gotham City. Also, when my son was little, we used to watch Batman: The Animated Series together so I was familiar with Harley Quinn, too. My son Rob and I got a kick out of her—she had a Brooklyn accent and my family is from Brooklyn. Of course, I had no idea at the time that years later, I would be collaborating with one of her co-creators on a novel about her!

Having recently read Paul Dini and Pat Cadigan’s Harley Quinn: Mad Love and James R. Tuck’s Venom: Lethal Protector, both part of Titan’s graphic to prose line, my reader brain, conditioned both for comics and for prose, became fascinated with how such an operation was even possible. Cadigan was kind enough to take a few minutes to answer some questions about how she and Dini worked together to give Harley Quinn’s Mad Love arc a second life as a traditional novel (while keeping it a non-traditional story).

Book Riot: When a writer and an artist do a graphic novel version of a comic, they have the opportunity to add: art allows not only for color, panel breakdown, and object placement to establish mood and setting without the push-pull of show versus tell and word count restrictions, but also for the use of facial expression and body language which many studies suggest are, to some extent universal, to assist in telling the story (not that telling a stories in comics is easier, simply different). Novelizing a comic takes away those tools, tools that were programmed into the original telling, leaving the author with words alone, which seems like a much more difficult process. Is that the case? How do you go about the translation? How do you tell a story that was created with art without that art? Is the task more viable when the character as well established or does that not play in? How did you go about translating Mad Love specifically? Do you think the process would be different if you were working on a different story? A less well known one? Less “famous” characters?

Pat Cadigan: Well, I’m not a comics writer—I’m a prose novelist, so I’m used to painting pictures with words. When I’m writing one of my own novels, I’m describing what I see in my mind. Having the comic to work from meant I had actual pictures to refer to. But there was also quite a lot in Paul Dini’s outline that had not appeared in a comic. Harley Quinn: Mad Love includes a lot of material that was never part of a graphic novel. Paul’s outline was so clear that it wasn’t difficult to “see” what he was “seeing.”

Perhaps the process would be different with a different story—I know that whenever I write a novel, whether it’s one of my own originals or a novelisation or a media tie-in, I have to get acquainted with the story and the characters in a new way. I have to figure out how I can tell the story in the clearest, most vivid way, so that readers can “see” what’s going on. I’m a very visual person anyway—when I read a book, I’m actually watching a movie unfold in my mind. But as I said, I’ve never written comics so I don’t really know what it’s like to shift gears.

It probably would be a lot different to work with characters who weren’t as well known—I didn’t have to explain a lot of background for Gotham or Arkham Asylum. I didn’t have to explain who Batman is and what he does, and everyone knows what he looks like. But I did have to make sure I was true to the characters as they exist. Fortunately for me, that wasn’t hard—I grew up reading DC Comics and I’m very familiar with Batman and Gotham City. Also, when my son was little, we used to watch Batman: The Animated Series together so I was familiar with Harley Quinn, too. My son Rob and I got a kick out of her—she had a Brooklyn accent and my family is from Brooklyn. Of course, I had no idea at the time that years later, I would be collaborating with one of her co-creators on a novel about her!

BR: Mad Love is a pivotal moment in the genesis of a beloved character about whom people have Very Strong Feelings. What is it like to step into a moment like that as as a writer? What are some of the exciting things about doing so? Is there anything you found particularly challenging about it?

PC: Although I was a DC Comics reader, I was never active in comics fandom so I wasn’t really aware of fan expectations. I knew there would be some fan reaction after the book came out but I was mainly focussed on the character and on Paul Dini’s outline. Paul’s vision was very clear and I wanted to be true to that.

The most challenging moment for me comes at what is the end of the comic Mad Love, when Harley Quinn is in Arkham, recovering from a seven-storey fall after the Joker throws her through a window. She’s trying to be strong and firm with herself, telling herself she’s done with the Joker for good, no more crazy, etc., and she suddenly spots the rose the Joker left for her with a get-well-soon note. Dr. Leland has just asked her how it feels to have devoted herself to a man who just threw her away and she says, “It feels like a kiss.”

I knew this was a nod to an old Rock’n’Roll song: “He Hit Me And It Felt Like A Kiss,” and Paul Dini has said as much. I didn’t want Harley to be a willing victim any more—a seven-storey fall is one hell of a wake-up call. But there are women who stay with their abusers because they are deeply in love with them. It’s hard to understand that when you’re looking at it from outside the relationship but it’s unrealistic to deny these women’s feelings. These women aren’t crazy but they’ve been isolated by their abusers so they no longer understand how unhealthy their situation is. Abusers keep their victims with them by giving them small doses of love and tenderness in between beatings—just enough to soften the victims’ resolve and decide to give the relationship another chance.

I didn’t “like” having Harley say, “It feels like a kiss.” No one I know thinks a seven-storey fall would feel like a kiss—I certainly don’t! But Harley was isolated and under the Joker’s control for a long time. It’s not so unrealistic to think that a sudden “loving” gesture from the Joker would suddenly make her all misty-eyed. But as it turns out it’s only temporary; she doesn’t return to the Joker immediately, which gives her the time and space to shake off his influence.

BR: What was the team dynamic like between you and Paul Dini? Did you know one another prior to the project? How often did you consult with one another? Was he more involved in the planning stages or did he also have a hand in the writing? What was it like to play in his sandbox?

PC: I’ve done novelisations and media tie-ins before, and I’m an old assignment writer from way back—I wrote greeting cards for Hallmark for ten years. So I’m comfortable with working with other people’s material. Paul Dini and I had never met; we communicated through our editor, Steve Saffel, which I think was the best way to do things. When I had questions, I contacted Steve. Steve contacted Paul, Paul gave him the answers, and Steve sent them to me. Doing things this way meant no one was out of the loop and everybody involved knew where everyone else was.

BR: There are a lot of Opinions and Feelings in the fandom about the relationship between Harley and the Joker. What’s your take as a writer? As a woman?

BR: Mad Love is a pivotal moment in the genesis of a beloved character about whom people have Very Strong Feelings. What is it like to step into a moment like that as as a writer? What are some of the exciting things about doing so? Is there anything you found particularly challenging about it?

PC: Although I was a DC Comics reader, I was never active in comics fandom so I wasn’t really aware of fan expectations. I knew there would be some fan reaction after the book came out but I was mainly focussed on the character and on Paul Dini’s outline. Paul’s vision was very clear and I wanted to be true to that.

The most challenging moment for me comes at what is the end of the comic Mad Love, when Harley Quinn is in Arkham, recovering from a seven-storey fall after the Joker throws her through a window. She’s trying to be strong and firm with herself, telling herself she’s done with the Joker for good, no more crazy, etc., and she suddenly spots the rose the Joker left for her with a get-well-soon note. Dr. Leland has just asked her how it feels to have devoted herself to a man who just threw her away and she says, “It feels like a kiss.”

I knew this was a nod to an old Rock’n’Roll song: “He Hit Me And It Felt Like A Kiss,” and Paul Dini has said as much. I didn’t want Harley to be a willing victim any more—a seven-storey fall is one hell of a wake-up call. But there are women who stay with their abusers because they are deeply in love with them. It’s hard to understand that when you’re looking at it from outside the relationship but it’s unrealistic to deny these women’s feelings. These women aren’t crazy but they’ve been isolated by their abusers so they no longer understand how unhealthy their situation is. Abusers keep their victims with them by giving them small doses of love and tenderness in between beatings—just enough to soften the victims’ resolve and decide to give the relationship another chance.

I didn’t “like” having Harley say, “It feels like a kiss.” No one I know thinks a seven-storey fall would feel like a kiss—I certainly don’t! But Harley was isolated and under the Joker’s control for a long time. It’s not so unrealistic to think that a sudden “loving” gesture from the Joker would suddenly make her all misty-eyed. But as it turns out it’s only temporary; she doesn’t return to the Joker immediately, which gives her the time and space to shake off his influence.

BR: What was the team dynamic like between you and Paul Dini? Did you know one another prior to the project? How often did you consult with one another? Was he more involved in the planning stages or did he also have a hand in the writing? What was it like to play in his sandbox?

PC: I’ve done novelisations and media tie-ins before, and I’m an old assignment writer from way back—I wrote greeting cards for Hallmark for ten years. So I’m comfortable with working with other people’s material. Paul Dini and I had never met; we communicated through our editor, Steve Saffel, which I think was the best way to do things. When I had questions, I contacted Steve. Steve contacted Paul, Paul gave him the answers, and Steve sent them to me. Doing things this way meant no one was out of the loop and everybody involved knew where everyone else was.

BR: There are a lot of Opinions and Feelings in the fandom about the relationship between Harley and the Joker. What’s your take as a writer? As a woman?

PC: I come from a rough background. My mother had the good sense to get both of us out of a very bad situation when I was young. But we weren’t well off; in our neighbourhood, it wasn’t Saturday night if the police weren’t called to someone’s house. We lived in an apartment building and I can remember my mother leaning out the kitchen window waving a broom and yelling at the man downstairs that if he didn’t stop hitting his wife, she’d come down there and shove the broom up his, er, nose. So yeah, I have some strong feelings about abusive relationships. I wasn’t comfortable writing about one. But it’s not something to ignore. The people who get into these relationships—and stay in them—aren’t stupid. I’ve known a number of highly intelligent women, capable in their careers, who have been drawn into relationships with people who aren’t worth the salt in their tears, to phrase a coin. Being strong and intelligent doesn’t mean you always make good choices.

Harley Quinn is a particularly complicated character because she’s actually supposed to be a villain. You’re not supposed to root for a villain…are you? Or are you? Harley sparks strong feelings in many fans—and not only female ones—because, villain or not, they don’t want her to submit to the Joker, who gleefully abuses her. On the other hand, just because she rejects the Joker doesn’t mean she’ll straighten up and become a white hat. She may break free of her abuser and still be a villain. She’s complicated; she confounds expectations. I love that in a character.

BR: How much research did you do on the characters and the backstory before you started writing? Did you read the graphic novel? Watch any specific episodes of the animated series? Any non-fiction research?

PC: As I said earlier, I was a DC Comics fan from childhood. I haven’t been reading comics much lately but I did read the comic Mad Love after I got the assignment. But also as I said earlier, I was familiar with Harley Quinn because I used to watch Batman: the Animated Series with my son when he was little. It was on every morning before school. We’d watch it together and then I’d walk him to school. (In case any parents are wondering how letting my kid watch TV before school affected him: he has a Master’s Degree in Japanese Cultural Studies and he works as an administrator for the London College Hospital medical school.) Of course, I rewatched the series and the Harley Quinn episodes in particular so I could re-familiarise myself with the character. Mostly, however, it was Paul Dini’s outline; his vision of Harley Quinn was perfectly clear.

BR: Why do you think Mad Love is an important story to tell or to continue to tell?

Personally, I think Mad Love is a brilliant take on a difficult subject—a smart, capable, beautiful woman taken in by a grotesque, insane, and abusive villain. Harley Quinn is complex, a strong woman with weaknesses. Most strong, intelligent women in any medium are portrayed as geniuses who always make the right choices. I know a lot of strong, intelligent women but they don’t always get everything right.

BR: Prior to Mad Love, most of your novels and stories have shaded toward sci-fi with the majority being more specifically in the realms of techno- and cyberpunk. You’ve also done some horror and written in the shared Battle Angel Alita and Wild Card universes. How did your previous work inform your take on Harley’s story? On the setting of Arkham? On the mythos of Gotham?

PC: Well, to be honest, besides Paul Dini’s brilliantly clear outline, I think I was most influenced by the TV series Gotham. I absolutely love how Gotham City is portrayed. And Arkham Asylum has figured prominently in many episodes, so I could get a clear image of what a grotesque place it was and so understand how Dr. Leland is struggling to make it more like a hospital and less like an inner circle of Hell. Of course, Harley Quinn doesn’t appear, although Catwoman and Poison Ivy do. They’re very young, not the seasoned criminals they become later.

As I said earlier, I’m a very visual person, so watching Gotham helped me see Gotham City from both the inside and the outside. When you’re *in* Gotham City, crazy costumed villains and a vigilante dressed like a bat become normalised. Coming in from the outside is something else. If you’re a villain like a mob boss, these are just things you can use to your advantage. But to a civilian—particularly a mental health professional—the crazy seems so thick you can cut it with a knife. Having Harley see Batman as a police-approved criminal rather than a hero and protector helped to build up her already existing problems with authority.

(Incidentally, I watch Arrow, Legends of Tomorrow, and The Flash, too. There’s a wonderful, albeit very brief, moment in Arrow when Amanda Waller is talking to Oliver Queen and John Diggle (I think) in the area where they keep prisoners locked up, and you hear a high, female voice call out, “Hey, does someone need therapy? I’m a licensed therapist!” And Amanda Waller bangs on the door to make her shut up. Nobody says so but I know that’s Harley Quinn. It gave me a chuckle.)

Of course, none of this answers your question as to how my previous work informed my take on Harley Quinn’s story. I’m not sure I can give you an answer to that. I had such a good time writing Harley Quinn: Mad Love and I think that above all informed my work. I enjoyed it from beginning to end.

BR: I really enjoyed your take on Batman—he seemed very much the sly, dry wit we all loved so much on the B:TAS. How did you capture that very specific Batman in prose? How did your previous work prepare you for that (monumental) task? How did it feel to join the pantheon of writers who have had the opportunity to craft the Bat, even in small snippets (because, let’s face it, who among us hasn’t wanted the chance)?

PC: I come from a rough background. My mother had the good sense to get both of us out of a very bad situation when I was young. But we weren’t well off; in our neighbourhood, it wasn’t Saturday night if the police weren’t called to someone’s house. We lived in an apartment building and I can remember my mother leaning out the kitchen window waving a broom and yelling at the man downstairs that if he didn’t stop hitting his wife, she’d come down there and shove the broom up his, er, nose. So yeah, I have some strong feelings about abusive relationships. I wasn’t comfortable writing about one. But it’s not something to ignore. The people who get into these relationships—and stay in them—aren’t stupid. I’ve known a number of highly intelligent women, capable in their careers, who have been drawn into relationships with people who aren’t worth the salt in their tears, to phrase a coin. Being strong and intelligent doesn’t mean you always make good choices.

Harley Quinn is a particularly complicated character because she’s actually supposed to be a villain. You’re not supposed to root for a villain…are you? Or are you? Harley sparks strong feelings in many fans—and not only female ones—because, villain or not, they don’t want her to submit to the Joker, who gleefully abuses her. On the other hand, just because she rejects the Joker doesn’t mean she’ll straighten up and become a white hat. She may break free of her abuser and still be a villain. She’s complicated; she confounds expectations. I love that in a character.

BR: How much research did you do on the characters and the backstory before you started writing? Did you read the graphic novel? Watch any specific episodes of the animated series? Any non-fiction research?

PC: As I said earlier, I was a DC Comics fan from childhood. I haven’t been reading comics much lately but I did read the comic Mad Love after I got the assignment. But also as I said earlier, I was familiar with Harley Quinn because I used to watch Batman: the Animated Series with my son when he was little. It was on every morning before school. We’d watch it together and then I’d walk him to school. (In case any parents are wondering how letting my kid watch TV before school affected him: he has a Master’s Degree in Japanese Cultural Studies and he works as an administrator for the London College Hospital medical school.) Of course, I rewatched the series and the Harley Quinn episodes in particular so I could re-familiarise myself with the character. Mostly, however, it was Paul Dini’s outline; his vision of Harley Quinn was perfectly clear.

BR: Why do you think Mad Love is an important story to tell or to continue to tell?

Personally, I think Mad Love is a brilliant take on a difficult subject—a smart, capable, beautiful woman taken in by a grotesque, insane, and abusive villain. Harley Quinn is complex, a strong woman with weaknesses. Most strong, intelligent women in any medium are portrayed as geniuses who always make the right choices. I know a lot of strong, intelligent women but they don’t always get everything right.

BR: Prior to Mad Love, most of your novels and stories have shaded toward sci-fi with the majority being more specifically in the realms of techno- and cyberpunk. You’ve also done some horror and written in the shared Battle Angel Alita and Wild Card universes. How did your previous work inform your take on Harley’s story? On the setting of Arkham? On the mythos of Gotham?

PC: Well, to be honest, besides Paul Dini’s brilliantly clear outline, I think I was most influenced by the TV series Gotham. I absolutely love how Gotham City is portrayed. And Arkham Asylum has figured prominently in many episodes, so I could get a clear image of what a grotesque place it was and so understand how Dr. Leland is struggling to make it more like a hospital and less like an inner circle of Hell. Of course, Harley Quinn doesn’t appear, although Catwoman and Poison Ivy do. They’re very young, not the seasoned criminals they become later.

As I said earlier, I’m a very visual person, so watching Gotham helped me see Gotham City from both the inside and the outside. When you’re *in* Gotham City, crazy costumed villains and a vigilante dressed like a bat become normalised. Coming in from the outside is something else. If you’re a villain like a mob boss, these are just things you can use to your advantage. But to a civilian—particularly a mental health professional—the crazy seems so thick you can cut it with a knife. Having Harley see Batman as a police-approved criminal rather than a hero and protector helped to build up her already existing problems with authority.

(Incidentally, I watch Arrow, Legends of Tomorrow, and The Flash, too. There’s a wonderful, albeit very brief, moment in Arrow when Amanda Waller is talking to Oliver Queen and John Diggle (I think) in the area where they keep prisoners locked up, and you hear a high, female voice call out, “Hey, does someone need therapy? I’m a licensed therapist!” And Amanda Waller bangs on the door to make her shut up. Nobody says so but I know that’s Harley Quinn. It gave me a chuckle.)

Of course, none of this answers your question as to how my previous work informed my take on Harley Quinn’s story. I’m not sure I can give you an answer to that. I had such a good time writing Harley Quinn: Mad Love and I think that above all informed my work. I enjoyed it from beginning to end.

BR: I really enjoyed your take on Batman—he seemed very much the sly, dry wit we all loved so much on the B:TAS. How did you capture that very specific Batman in prose? How did your previous work prepare you for that (monumental) task? How did it feel to join the pantheon of writers who have had the opportunity to craft the Bat, even in small snippets (because, let’s face it, who among us hasn’t wanted the chance)?

PC: Actually, Harley was my main focus. Perhaps because I knew her from B:TAS, I unconsciously modelled Batman from the series as well, although mostly I took him as is from the graphic novel Mad Love, which was what Paul Dini wanted. But I have to say that I wasn’t thinking of writing Batman as a monumental task while the work was in progress. I just wanted to get the character right—in particular, to make it clear that he wasn’t the demonised bad guy Harley Quinn had made him out to be.

BR: What are you working on now?

PC: I’d tell you but then I’d have to kill you.

Just kidding. I’m doing some short fiction and working on a novel that jumps off from the end of the novelette I won a Hugo for back in 2013. The novelette was “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out For Sushi.” Working title of the novel: See You When You Get There.

BR: What are you reading now?

PC: Lately I’ve been reading a lot of research for the novel I’m working on—books on quantum mechanics, string theory, the Tarot, and the I Ching, although I did take a few moments to read Stephen King’s two latest: The Outsider and Elevation.

PC: Actually, Harley was my main focus. Perhaps because I knew her from B:TAS, I unconsciously modelled Batman from the series as well, although mostly I took him as is from the graphic novel Mad Love, which was what Paul Dini wanted. But I have to say that I wasn’t thinking of writing Batman as a monumental task while the work was in progress. I just wanted to get the character right—in particular, to make it clear that he wasn’t the demonised bad guy Harley Quinn had made him out to be.

BR: What are you working on now?

PC: I’d tell you but then I’d have to kill you.

Just kidding. I’m doing some short fiction and working on a novel that jumps off from the end of the novelette I won a Hugo for back in 2013. The novelette was “The Girl-Thing Who Went Out For Sushi.” Working title of the novel: See You When You Get There.

BR: What are you reading now?

PC: Lately I’ve been reading a lot of research for the novel I’m working on—books on quantum mechanics, string theory, the Tarot, and the I Ching, although I did take a few moments to read Stephen King’s two latest: The Outsider and Elevation.

Other novels included in the Titan Project: The Killing Joke (September 2018), The Court of Owls (February 2019), Deadpool: PAWS (April 2018), Civil War (April 2018), Ant Man: Natural Enemy (July 2018), Spider-Man: Forever Young (October 2018), Spider-Man: Hostile Takeover (August 2018), Avengers: Everybody Wants to Rule the World (April 2018), Who is Black Panther (April 2018), and Captain Marvel: Liberation Run (February 2019).