On Posthumous Editing: Should Books Be Edited for Contemporary Audiences?

What do you remember best about your favorite childhood book? Is it the setting, the characters, the descriptions of food? For me, it’s always the way it made me feel. Usually, the feeling was “less alone,” “hopeful,” or “indignantly determined.” Reading a classic book with decades of history behind it was exciting to me to see why the book was so famous and what made it appealing to different generations. Was I having the same reaction to a book as generations of other readers? What about the past was different, and what was the same? Currently, there’s a bit of a trend of posthumous editing of classic fiction to update the works to be more appealing to contemporary audiences.

I say “trend” because it has recently occurred with the blessing of four major author estates. Dr. Seuss, Roald Dahl, Ian Fleming, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Agatha Christie. In the case of Dr. Seuss and Roald Dahl, the edits are argued to be necessary for sensitivity purposes. They’re for kids, and kids shouldn’t have to be exposed to the bigoted beliefs of the authors whose books are ostensibly giving kids lessons about morality. Fleming, Le Guin, and Christie are titans of genre fiction, and their respective estates likely rely on regular sales, in addition to movie and television option agreements and royalties.

The edits have caused a variety of reactions, from The Washington Post’s editorial board railing against the “threat to free expression” to The New York Times’s more measured take, to arguments to leave authors like Roald Dahl in the past. Since this trend seems to be getting integrated into the processes of managing author estates and new printings of classic works, we should look at the argument from all sides and understand what this means for the future of publishing and readers in general.

What’s being edited?

Dr. Seuss’s estate announced last year that six of his poorly-selling titles with dated content would no longer be in print. By contrast, Dahl’s estate removed some unfriendly words: “Classics by Roald Dahl have been stripped of adjectives like ‘fat’ and ‘ugly’ along with references to characters’ gender and skin color.” Ursula K. Le Guin’s son Theo, who manages her work, allowed editors to remove ableist words like “lame” and “dumb” from her Catwings series.

For Fleming and Christie, the estates have decided to cut racial slurs and outdated language from the books. Mystery and spy thrillers are generally meant for cozy reading, and coming across a slur or one of Fleming’s more colorful descriptions of a female body could be disruptive. It’s argued to be for the readers so they can continue to experience the joy of these stories without the baggage of past prejudices. But it’s also for the continued relevance of the brand.

The Pros and Cons of Posthumous Editing

The biggest argument in favor of posthumous editing is for contemporary readers to continue to connect to stories that have delighted readers for generations, without the jarring language that will take you out of the story. However, it’s hard to argue that continued profits are not a major incentive as well. The Dahl estate especially has to scramble to stay relevant. The updated movie version of The Witches does not feature the hooked noses of the original movie adaptation and book. I’m sure the Wonka movie with Timothée Chalamet will include some tepid justification for the indentured servitude of the Oompa Loompas.

The Washington Post’s editors argue vehemently against the practice of editing and ask instead for editors “to surround original works with context, in the form of critical introductions as well as annotations in new editions, wherever possible. It’s urgent to explain, in introductions and scholarly comments, why certain words are harmful; about a given author’s personal biases and politics; and how each shaped their view of the world.”

At its core, this would be no different from a Folger’s Shakespeare edition with the definitions on the left side and the text of the play on the right. However, it doesn’t entirely seem feasible for books pitched at young readers. Kids are smart and curious, of course, and will undoubtedly seek out information related to books that spark their interest. Filling a children’s book with in-text explanations makes reading Dahl sound more like homework than fun. (But some kids like me enjoyed homework, so who’s to say how badly this would affect sales.)

I am not a parent, so I don’t know how difficult it is these days to find appropriate books for children. I’ve argued in the past for children to have access to whatever they want to read, but it can be daunting. It’s a safe bet to rely on an author who has sparked children’s love of reading for decades, as opposed to an unknown entity. Removing outdated language from old children’s books means they’re still a safe brand to turn to. Roald Dahl and Dr. Seuss are like the Applebee’s of children’s books. They might not be the best, but you know what you are going to get.

Posthumous editing might even have been sanctioned by some of the authors whose estates do it: it’s not out of the ordinary for living authors to change passages voluntarily. Even Roald Dahl did it: “in the 1970s, [he] made changes to ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.’ Faced with complaints that his depiction of the factory workers as dark-skinned pygmies from Africa was racist, he changed the workers into Oompa Loompas, small people from a fictional country called Loompaland.” Even more recently, in 2021, Casey McQuiston and Elin Hildebrand both made edits to their uber-popular books, apparently due to social media backlash.

For Ian Fleming and Agatha Christie, it’s a little more complicated. Annotations would be a good opportunity for readers of those books to learn more about the cultural conditions around their writing. But the characters of their books are tied to ongoing media brands: James Bond movies, and Kenneth Branagh’s quest to make boring Agatha Christie movies for the rest of his career. The Bond brand extends to the books. If someone comes to Bond through the contemporary films, the books will probably feel dissonant. It’s all about brand integration.

For an author like Agatha Christie, edits to racist language feel important to preserve the cozy mystery experience of reading the novel. The idea is to make the books accessible and sensitive to all readers, as opposed to just white ones. The counterpoint is that there are plenty of authors of color working in the mystery genre today, even writing in the historical English countryside mystery genre. Christie is a starting point of inspiration to a vast genre, so it is not a discredit to her legacy to point out that her work is specific to the first half of the 20th century and its cultural context.

If updating these books is just a craven capitalist necessity, it can feel a little histrionic to call the practice a major threat to free speech. The much more dominant threat right now comes from conservative book bans across the United States.

At the same time, I understand the fear. If any book can be edited at any time, publishers can bend to the whims of conservative fear mongers and alt-right hate groups. A few months ago, Maggie Tokuda-Hall refused a request from her publisher, Scholastic, to remove mentions of race from an author’s note. That controversy was a bleak harbinger of what could be down the road as more conservative, “parents’ rights” groups gain control of local and federal government. In an ironic twist, the parents who would want mentions of slavery removed from history textbooks would probably cry censorship at the edits made to Ian Fleming.

Changing with the Times

The vast majority of the written word is lost to time. Think of the epic cycle: we have evidence of the existence of Ancient Greek epic poems that we have no real record of because they are referenced in later works that were saved and rewritten. The Iliad and The Odyssey have survived, but Homer was an orator, not a writer. The definitive version that we do have is likely cobbled together from a variety of sources. That is not a knock against it: the poems are in fact testaments to a community’s need to tell stories and preserve history. Those stories used to change every time they were retold. Posthumous editing is not the same as the practice of passing down mythology, but it reflects our need to re-contextualize stories to what society finds currently important.

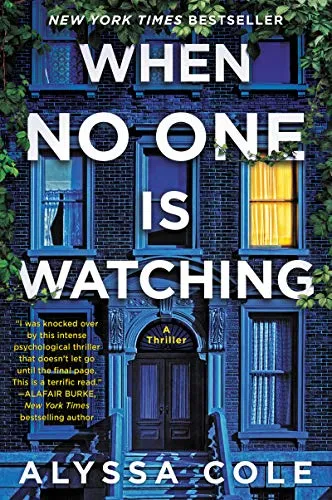

We don’t need to update authors’ books to reflect contemporary values because our contemporary values are reflected by authors writing books right now. Alyssa Cole’s When No One Is Watching is just as harrowing as a Christie original, but it’s about how we live now. Dahl’s work especially fails to relate to kids today, and his bigoted beliefs are all over his books, whether you remove the words or not. And once a precedent is set for constant editing to remove possibly offensive content, people who hate mentions of queerness, race, disability, and other marginalized identities will mobilize and force publishers to remove what they find distasteful.

My favorite activity is digging through out-of-print pulp novels at secondhand bookstores. They reflect the various anxieties of the time that authors responded to. What literary work gets preserved also reflects our societal values and how we want to communicate about them. Letting once-famous books fade in relevance doesn’t diminish the value they had at the time, and hopefully libraries will always be able to provide readers with the past and present of literature.

The problem that posthumous editing is attempting to solve should actually be solved with better literary education, more robust libraries where an expert can walk you through literary history, and publishing companies uplifting contemporary voices over the “safer” option of a well-known IP brand.