Mohican Forest, Floating City, and Physician Poet

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Early in the film The Last of Mohicans, a column of Red Coats dispatched from Albany marches through wild grass before edging inside a wall of dense Adirondack forest. The year is 1757, and beyond the carriages and colonial offices of Albany there’s true wilderness, where geopolitical ambitions have unleashed the slashing hatchet and whistling cannonball of the French-Indian War, fought among a handful of forts staked out on the grounds of a native civilization hostile to and seriously endangered by the encroaching European West.

It’s a powerful image: uniformed in imperial red, a world away from home, the colonial soldier on the march into the dark of ancient forest. This is the audacious bravery forged by discipline, entitlement, naivety, and greed fueling the colonization of a distant land and a people who will be made to surrender

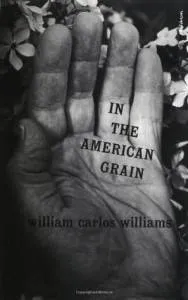

I was happy to see the movie again as part of a Michael Mann retrospective this winter in Brooklyn. I’ve been thinking more about our American forebears since last fall, when I’d begun reading In the American Grain, a history of prominent Americans written by William Carlos Williams and first published in 1925. Williams is among the country’s most important poets, known for his insistence on the unadorned in image and speech that contributed to an early 20th century shift in the American poetic vision. I’ve quoted one of his best known poems below. The title itself highlights Williams’s emphasis on everyday speech. Best to read it out loud to hear the inherent assertion and weight of even a few, seemingly simple words.

This is Just to Say

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

Take a moment now and imagine yourself as the guilty offender. Savor that final icy plum. Maybe you run your tongue along your upper lip as you now begin to pen a short note describing just how very, very sorry you truly feel. This is just to say . . .

Last November, after tidying admission tags, event schedules, and expo maps, I was able to read a couple early chapters of In the American Grain while staffing a mostly quiet end-of-afternoon reception shift at the first annual Book Riot Live. This celebration of all things books will return again this fall to Manhattan’s Far West Side, where the Hudson nears the end of its sweep down from the Adirondacks and eventually past the Statue of Liberty and out into the Atlantic. Along with what is inarguably one of America’s great rivers, two prominent sights landmark this part of New York City. The first, permanently docked a few steps from the expo hall, is the USS Intrepid. The fourth ship in U.S. naval history to carry its name, the Intrepid served in the Pacific island battles of World War II (surviving kamikaze and torpedo strikes), then later as a platform for Vietnam bombing runs, and in the interim as a recovery ship for Mercury and Gemini space missions. Today the Intrepid is a museum featuring the space shuttle Enterprise and elevated views south into the towering steel exoskeletons of the largest real estate development in American history.

According to a recent Fortune description, this 42-square-acre development—the Hudson Yards—“floats on a technically advanced network of steel beams, concrete, and tunnels” built above rail yards that via tracks beneath the Hudson link the city with mainland America. This floating platform will include several skyscrapers—the tallest towering 92 stories—as part of a project estimated to cost $20 billion. A few more numbers: 1) upon completion in 2024, the area is expected to receive about 65,000 visitors daily; 2) to float a skyscraper you need 90-ton steel columns forged in a Virginia facility that was constructed just for this purpose; 3) these columns can only be lifted by six cranes currently operating in the U.S.; and 4) a quick language aside: $20 billion is only three words.

In what admittedly has been a bit of a no man’s land between Midtown West and the waterfront—Hell’s Kitchen, a name that speaks to the neighborhood’s past and will no doubt be consigned as quickly as possible to the confetti of developers’ shredding bins—there was nonetheless the usual neighborhood system of small business, apartment, and school, and between rezoning and demolition the streetscape now being raised from the ground up will likely appear dropped straight from the sky. Perhaps in that sense, the Hudson Yards may seem to the grizzled longtime New Yorker something very marginally like the beams of The Mayflower might have seemed to the Native Americans. In In the American Grain, Williams begins his survey about 600 years before Plymouth Rock with Erik the Red. What you find in this first chapter is not the work of the “professional historian.” It’s the close first person narration of an enraged, outcast Norseman. Williams begins this imagined account by “Red Eric” (note the Americanization) recently exiled by his people for a killing precipitated by a property dispute:

Rather the ice than their way: to take what is mine by single strength, theirs by the crookedness of their law. But they have marked me—even to myself. Because I am not like them, I am evil. I cannot get my hands on it: I, murderer, outlaw, outcast even from Iceland. Because their way is the just way and my way—the way of the kings and my father—crosses them: weaklings holding together to appear strong. But I am alone, though in Greenland.

This chapter, which takes readers along with Erik’s descendants to the first murderous European settlement in North America (Vinland), directly precedes “The Discovery of the Indies,” a chapter in which much of the narrative seems lifted from the journals of Columbus. These early chapters establish Williams’s idiosyncratic approach: interwoven with his own analysis, In the American Grain presents a mix of imagined narrations and lengthily-excerpted historical documents that include Cotton Mather’s accounts of the Salem Witch Trials, sections of Poor Richard’s Almanac, and letters from Revolutionary War sailor John P. Jones. One essential goal of the book is to immerse the contemporary American in the language of our shared past and in the real-time logic and thoughts of epic Euro-Americans: Cortez arriving in Tenochtictlan, the survivors of DeSoto’s expedition toeing the banks of the Mississippi, Daniel Boone leaving behind the light of his hearth and walking off into the true unknown . . .

Like America, Williams’s book has its flaws. The mix of sources can result in rough transitions between chapters, at times the sources themselves can feel extremely tedious, and Williams’s stylistic emphasis on an almost improvisational immediacy can lead to mangled and mysterious phrasing. These features of the read, however, are essential to Williams’s purpose. What is less so is the occasionally-surfacing prejudices of even a progressive thinker like Williams, which a more generous reader might attribute as a consequence of his time. Despite his intimate, long career as a traveling physician whose clients included poor and minority patients, Williams’s single brief chapter on African Americans—“The Advent of the Slaves”— is paternalistic and overly simplistic. His writing about women can also feel problematic. This includes his take on the failure of the country’s first century to produce a fully-realized woman:

But [producing] a true woman in flower, never. Emily Dickinson, starving of passion in her father’s garden, is the very nearest we have ever been—starving . . . The first ones died shooting children against the wilderness like cannonballs.

It should be noted that this writing on the American woman is contextualized within Williams’s larger critique of American culture and its constraints, including the Puritanical spirit he feels has haunted America since the Pilgrims. Williams has little positive to say about this early American people and their continuing hold: “It is still today the Puritan who keeps his frightened grip upon the throat of the world lest it should prove him—empty.” For Williams, mostly undiscovered in the uncertainty of the early colonists’ circumstances was the almost truly unlimited possibility they were offered by the “New World”:

Clinging narrowly to their new foothold, dependent still on sailing vessels for a contact none too swift or certain with “home,” the colonists looked with fear to the west. They worked hard and for the most part throve, suffering the material lacks of their exposed condition with intention. But they suffered also privations not even to be estimated, cramping and demeaning for a people used to a world less primitively rigorous. A spirit of insecurity calling upon thrift and self-denial remained their basic mood. Opposed to this lay the forbidden wealth of the Unknown.

Implicit throughout Williams’s survey is this call for the realization of something previously unknown, an authentically new human character: the American. This frames his admiration of the Indian, his criticism of Mather and Franklin, his curiosity at Washington’s restraint, his praise for Boone and Burr, and his love of Poe as a first uniquely American literary voice. One of Williams’s central claims is a subconscious awareness among contemporary Americans of a lack of true authenticity in how we make our American lives. By “authentic,” Williams means a way of life expressive of humanity at our wild unruly true beautiful best. I don’t think I’m overstating his view. “The land! don’t you feel it?” Williams asks. “Doesn’t it make you want to go out and lift dead Indians tenderly from their graves, to steal from them—as if it must be clinging even to their corpses—some authenticity…”

I was happy to see the movie again as part of a Michael Mann retrospective this winter in Brooklyn. I’ve been thinking more about our American forebears since last fall, when I’d begun reading In the American Grain, a history of prominent Americans written by William Carlos Williams and first published in 1925. Williams is among the country’s most important poets, known for his insistence on the unadorned in image and speech that contributed to an early 20th century shift in the American poetic vision. I’ve quoted one of his best known poems below. The title itself highlights Williams’s emphasis on everyday speech. Best to read it out loud to hear the inherent assertion and weight of even a few, seemingly simple words.

This is Just to Say

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

Take a moment now and imagine yourself as the guilty offender. Savor that final icy plum. Maybe you run your tongue along your upper lip as you now begin to pen a short note describing just how very, very sorry you truly feel. This is just to say . . .

Last November, after tidying admission tags, event schedules, and expo maps, I was able to read a couple early chapters of In the American Grain while staffing a mostly quiet end-of-afternoon reception shift at the first annual Book Riot Live. This celebration of all things books will return again this fall to Manhattan’s Far West Side, where the Hudson nears the end of its sweep down from the Adirondacks and eventually past the Statue of Liberty and out into the Atlantic. Along with what is inarguably one of America’s great rivers, two prominent sights landmark this part of New York City. The first, permanently docked a few steps from the expo hall, is the USS Intrepid. The fourth ship in U.S. naval history to carry its name, the Intrepid served in the Pacific island battles of World War II (surviving kamikaze and torpedo strikes), then later as a platform for Vietnam bombing runs, and in the interim as a recovery ship for Mercury and Gemini space missions. Today the Intrepid is a museum featuring the space shuttle Enterprise and elevated views south into the towering steel exoskeletons of the largest real estate development in American history.

According to a recent Fortune description, this 42-square-acre development—the Hudson Yards—“floats on a technically advanced network of steel beams, concrete, and tunnels” built above rail yards that via tracks beneath the Hudson link the city with mainland America. This floating platform will include several skyscrapers—the tallest towering 92 stories—as part of a project estimated to cost $20 billion. A few more numbers: 1) upon completion in 2024, the area is expected to receive about 65,000 visitors daily; 2) to float a skyscraper you need 90-ton steel columns forged in a Virginia facility that was constructed just for this purpose; 3) these columns can only be lifted by six cranes currently operating in the U.S.; and 4) a quick language aside: $20 billion is only three words.

In what admittedly has been a bit of a no man’s land between Midtown West and the waterfront—Hell’s Kitchen, a name that speaks to the neighborhood’s past and will no doubt be consigned as quickly as possible to the confetti of developers’ shredding bins—there was nonetheless the usual neighborhood system of small business, apartment, and school, and between rezoning and demolition the streetscape now being raised from the ground up will likely appear dropped straight from the sky. Perhaps in that sense, the Hudson Yards may seem to the grizzled longtime New Yorker something very marginally like the beams of The Mayflower might have seemed to the Native Americans. In In the American Grain, Williams begins his survey about 600 years before Plymouth Rock with Erik the Red. What you find in this first chapter is not the work of the “professional historian.” It’s the close first person narration of an enraged, outcast Norseman. Williams begins this imagined account by “Red Eric” (note the Americanization) recently exiled by his people for a killing precipitated by a property dispute:

Rather the ice than their way: to take what is mine by single strength, theirs by the crookedness of their law. But they have marked me—even to myself. Because I am not like them, I am evil. I cannot get my hands on it: I, murderer, outlaw, outcast even from Iceland. Because their way is the just way and my way—the way of the kings and my father—crosses them: weaklings holding together to appear strong. But I am alone, though in Greenland.

This chapter, which takes readers along with Erik’s descendants to the first murderous European settlement in North America (Vinland), directly precedes “The Discovery of the Indies,” a chapter in which much of the narrative seems lifted from the journals of Columbus. These early chapters establish Williams’s idiosyncratic approach: interwoven with his own analysis, In the American Grain presents a mix of imagined narrations and lengthily-excerpted historical documents that include Cotton Mather’s accounts of the Salem Witch Trials, sections of Poor Richard’s Almanac, and letters from Revolutionary War sailor John P. Jones. One essential goal of the book is to immerse the contemporary American in the language of our shared past and in the real-time logic and thoughts of epic Euro-Americans: Cortez arriving in Tenochtictlan, the survivors of DeSoto’s expedition toeing the banks of the Mississippi, Daniel Boone leaving behind the light of his hearth and walking off into the true unknown . . .

Like America, Williams’s book has its flaws. The mix of sources can result in rough transitions between chapters, at times the sources themselves can feel extremely tedious, and Williams’s stylistic emphasis on an almost improvisational immediacy can lead to mangled and mysterious phrasing. These features of the read, however, are essential to Williams’s purpose. What is less so is the occasionally-surfacing prejudices of even a progressive thinker like Williams, which a more generous reader might attribute as a consequence of his time. Despite his intimate, long career as a traveling physician whose clients included poor and minority patients, Williams’s single brief chapter on African Americans—“The Advent of the Slaves”— is paternalistic and overly simplistic. His writing about women can also feel problematic. This includes his take on the failure of the country’s first century to produce a fully-realized woman:

But [producing] a true woman in flower, never. Emily Dickinson, starving of passion in her father’s garden, is the very nearest we have ever been—starving . . . The first ones died shooting children against the wilderness like cannonballs.

It should be noted that this writing on the American woman is contextualized within Williams’s larger critique of American culture and its constraints, including the Puritanical spirit he feels has haunted America since the Pilgrims. Williams has little positive to say about this early American people and their continuing hold: “It is still today the Puritan who keeps his frightened grip upon the throat of the world lest it should prove him—empty.” For Williams, mostly undiscovered in the uncertainty of the early colonists’ circumstances was the almost truly unlimited possibility they were offered by the “New World”:

Clinging narrowly to their new foothold, dependent still on sailing vessels for a contact none too swift or certain with “home,” the colonists looked with fear to the west. They worked hard and for the most part throve, suffering the material lacks of their exposed condition with intention. But they suffered also privations not even to be estimated, cramping and demeaning for a people used to a world less primitively rigorous. A spirit of insecurity calling upon thrift and self-denial remained their basic mood. Opposed to this lay the forbidden wealth of the Unknown.

Implicit throughout Williams’s survey is this call for the realization of something previously unknown, an authentically new human character: the American. This frames his admiration of the Indian, his criticism of Mather and Franklin, his curiosity at Washington’s restraint, his praise for Boone and Burr, and his love of Poe as a first uniquely American literary voice. One of Williams’s central claims is a subconscious awareness among contemporary Americans of a lack of true authenticity in how we make our American lives. By “authentic,” Williams means a way of life expressive of humanity at our wild unruly true beautiful best. I don’t think I’m overstating his view. “The land! don’t you feel it?” Williams asks. “Doesn’t it make you want to go out and lift dead Indians tenderly from their graves, to steal from them—as if it must be clinging even to their corpses—some authenticity…”

I struggle with this book. I am fascinated by the history and the people it presents and by its almost countercultural insistence on the possibility of achieving something authentically new in American life that must be simultaneously rooted in an intimate, felt sense of the American past. I walk a city where skyscrapers rise atop floating platforms over railroads tunneled beneath a river that shaped whole civilizations before the first European explorers arrived seeking a passage to China, a river that now docks a World War II aircraft carrier that recovered the early astronauts. The cover of In the American Grain features a black-and-white photo of a close-up, deeply-lined open palm cupping the words of the title. Inside, in his introduction, poet and publisher James Laughlin calls In the American Grain “a source book of highly individual and radical discoveries” and offers a warning:

Too many writers have already lost themselves . . . the images of rebirth and the sensations of becoming reiterated with alarming regularity . . . as though we waked each morning to find a new world stillborn at our door.

For several months now, I’ve considered Laughlin’s warning against a literature of rebirth and its connection with Williams’s call to newness and authenticity. Count me among believers that literature and especially poetry can provide a potential antidote to this American moment characterized by so much noise, when settling inside the lines of a good book can feel like at least the opportunity for a badly-needed re-awakening of some authentic part of myself. I don’t know if I’d call it rebirth but just after finishing the best reads, looking up from the page, seeing the world to be not quite as it was before, a kind of new vision that also feels like remembering something essential . . .

Still, even 90 years after the publication of In the American Grain, I can’t dismiss Laughlin’s point. If this particular sense of re-awakening/rebirth becomes a defining feature of our contemporary literature, familiarity and habit will wear its authenticity, and a false sense of awakening and rebirth is the kind of lie that reduces the present moment to illusion. As Williams repeatedly asserts and as walking forest trails and city sidewalks underscores, we are people living in the vast landscape of sequential time. And while Now is always where we find ourselves, whatever wild-beautiful-true thing we might do must include an intimate knowing of the beginnings, the names, the from who and where and when, and then maybe a glimpse: something new.

I struggle with this book. I am fascinated by the history and the people it presents and by its almost countercultural insistence on the possibility of achieving something authentically new in American life that must be simultaneously rooted in an intimate, felt sense of the American past. I walk a city where skyscrapers rise atop floating platforms over railroads tunneled beneath a river that shaped whole civilizations before the first European explorers arrived seeking a passage to China, a river that now docks a World War II aircraft carrier that recovered the early astronauts. The cover of In the American Grain features a black-and-white photo of a close-up, deeply-lined open palm cupping the words of the title. Inside, in his introduction, poet and publisher James Laughlin calls In the American Grain “a source book of highly individual and radical discoveries” and offers a warning:

Too many writers have already lost themselves . . . the images of rebirth and the sensations of becoming reiterated with alarming regularity . . . as though we waked each morning to find a new world stillborn at our door.

For several months now, I’ve considered Laughlin’s warning against a literature of rebirth and its connection with Williams’s call to newness and authenticity. Count me among believers that literature and especially poetry can provide a potential antidote to this American moment characterized by so much noise, when settling inside the lines of a good book can feel like at least the opportunity for a badly-needed re-awakening of some authentic part of myself. I don’t know if I’d call it rebirth but just after finishing the best reads, looking up from the page, seeing the world to be not quite as it was before, a kind of new vision that also feels like remembering something essential . . .

Still, even 90 years after the publication of In the American Grain, I can’t dismiss Laughlin’s point. If this particular sense of re-awakening/rebirth becomes a defining feature of our contemporary literature, familiarity and habit will wear its authenticity, and a false sense of awakening and rebirth is the kind of lie that reduces the present moment to illusion. As Williams repeatedly asserts and as walking forest trails and city sidewalks underscores, we are people living in the vast landscape of sequential time. And while Now is always where we find ourselves, whatever wild-beautiful-true thing we might do must include an intimate knowing of the beginnings, the names, the from who and where and when, and then maybe a glimpse: something new.

William Carlos Williams

I struggle with this book. I am fascinated by the history and the people it presents and by its almost countercultural insistence on the possibility of achieving something authentically new in American life that must be simultaneously rooted in an intimate, felt sense of the American past. I walk a city where skyscrapers rise atop floating platforms over railroads tunneled beneath a river that shaped whole civilizations before the first European explorers arrived seeking a passage to China, a river that now docks a World War II aircraft carrier that recovered the early astronauts. The cover of In the American Grain features a black-and-white photo of a close-up, deeply-lined open palm cupping the words of the title. Inside, in his introduction, poet and publisher James Laughlin calls In the American Grain “a source book of highly individual and radical discoveries” and offers a warning:

Too many writers have already lost themselves . . . the images of rebirth and the sensations of becoming reiterated with alarming regularity . . . as though we waked each morning to find a new world stillborn at our door.

For several months now, I’ve considered Laughlin’s warning against a literature of rebirth and its connection with Williams’s call to newness and authenticity. Count me among believers that literature and especially poetry can provide a potential antidote to this American moment characterized by so much noise, when settling inside the lines of a good book can feel like at least the opportunity for a badly-needed re-awakening of some authentic part of myself. I don’t know if I’d call it rebirth but just after finishing the best reads, looking up from the page, seeing the world to be not quite as it was before, a kind of new vision that also feels like remembering something essential . . .

Still, even 90 years after the publication of In the American Grain, I can’t dismiss Laughlin’s point. If this particular sense of re-awakening/rebirth becomes a defining feature of our contemporary literature, familiarity and habit will wear its authenticity, and a false sense of awakening and rebirth is the kind of lie that reduces the present moment to illusion. As Williams repeatedly asserts and as walking forest trails and city sidewalks underscores, we are people living in the vast landscape of sequential time. And while Now is always where we find ourselves, whatever wild-beautiful-true thing we might do must include an intimate knowing of the beginnings, the names, the from who and where and when, and then maybe a glimpse: something new.

I struggle with this book. I am fascinated by the history and the people it presents and by its almost countercultural insistence on the possibility of achieving something authentically new in American life that must be simultaneously rooted in an intimate, felt sense of the American past. I walk a city where skyscrapers rise atop floating platforms over railroads tunneled beneath a river that shaped whole civilizations before the first European explorers arrived seeking a passage to China, a river that now docks a World War II aircraft carrier that recovered the early astronauts. The cover of In the American Grain features a black-and-white photo of a close-up, deeply-lined open palm cupping the words of the title. Inside, in his introduction, poet and publisher James Laughlin calls In the American Grain “a source book of highly individual and radical discoveries” and offers a warning:

Too many writers have already lost themselves . . . the images of rebirth and the sensations of becoming reiterated with alarming regularity . . . as though we waked each morning to find a new world stillborn at our door.

For several months now, I’ve considered Laughlin’s warning against a literature of rebirth and its connection with Williams’s call to newness and authenticity. Count me among believers that literature and especially poetry can provide a potential antidote to this American moment characterized by so much noise, when settling inside the lines of a good book can feel like at least the opportunity for a badly-needed re-awakening of some authentic part of myself. I don’t know if I’d call it rebirth but just after finishing the best reads, looking up from the page, seeing the world to be not quite as it was before, a kind of new vision that also feels like remembering something essential . . .

Still, even 90 years after the publication of In the American Grain, I can’t dismiss Laughlin’s point. If this particular sense of re-awakening/rebirth becomes a defining feature of our contemporary literature, familiarity and habit will wear its authenticity, and a false sense of awakening and rebirth is the kind of lie that reduces the present moment to illusion. As Williams repeatedly asserts and as walking forest trails and city sidewalks underscores, we are people living in the vast landscape of sequential time. And while Now is always where we find ourselves, whatever wild-beautiful-true thing we might do must include an intimate knowing of the beginnings, the names, the from who and where and when, and then maybe a glimpse: something new.