Male Leads in Fiction Sell 10 Million More Books on Average Than Female Leads

It should come as no surprise to longtime readers, as well as anyone remotely familiar with why feminism remains a necessity today, that male-identifying writers and characters garner more positive reviews and descriptions than female. A new study by SuperSummary, a company which provides study guides for fiction and nonfiction, explored gender bias in their latest study “Strong Man; Beautiful Woman.”

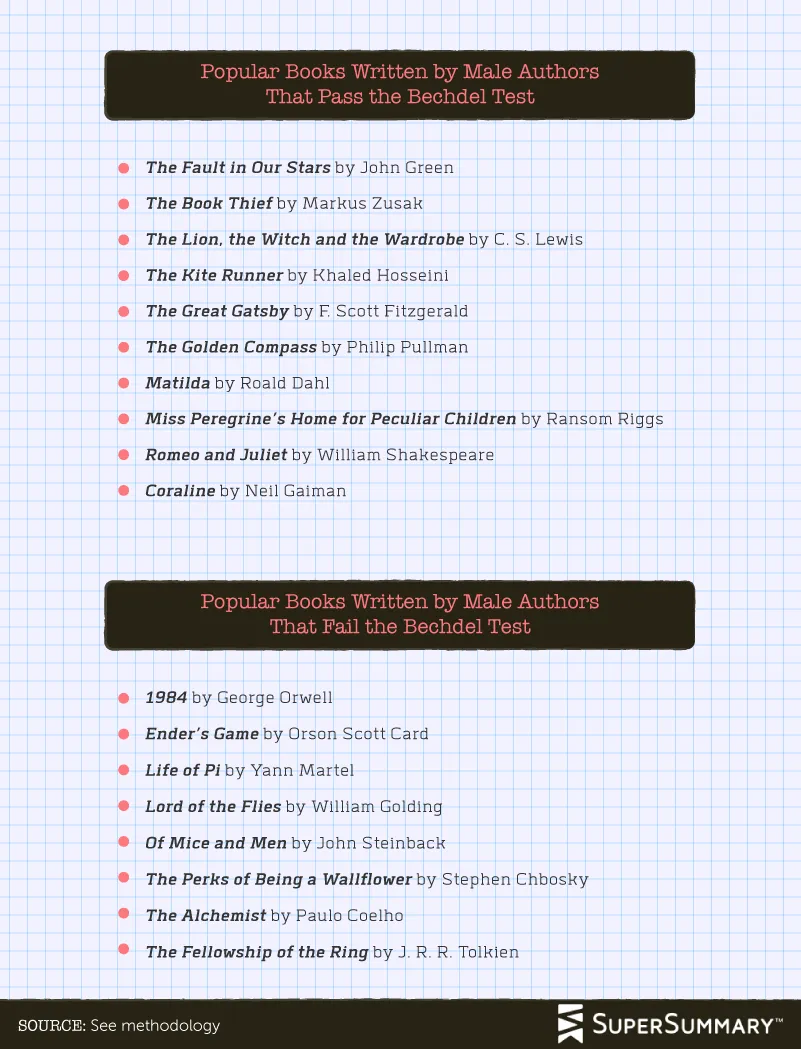

SuperSummary used the Bechdel Test as a jumping off point for their research. This handy tool, named after Alison Bechdel’s 1985 comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For,” is a simplified means of determining sexism in literature. Though it’s overly simplified, the Bechdel Test has three requirements: (1) there are two named female characters (2) who talk with each other (3) about something other than a man.

The research began by compiling a list of 200 bestselling fiction books. Which books were compiled isn’t addressed in the study—a limitation noted about a previous study of theirs—but given that they are bestsellers, they’re already leaning white and male. The books on the list were published between 1300 and 2015. Those books were put to the Bechdel Test, and then the researchers used the Corpus of Historical American English to find words most frequently associated with gender nouns and pronouns from between 1800 and 2009. SuperSummary notes the limitations of both their list, as well as their reliance on the Corpus, though they do not address the lack of gender diversity in the research. This study focused entirely on male and female descriptions, with the only divergence on this binary being “no gender assigned.”

There is a gender bias in bestselling fiction, according to their research. This isn’t surprising, of course, but the data here to showcase it are worth exploring.

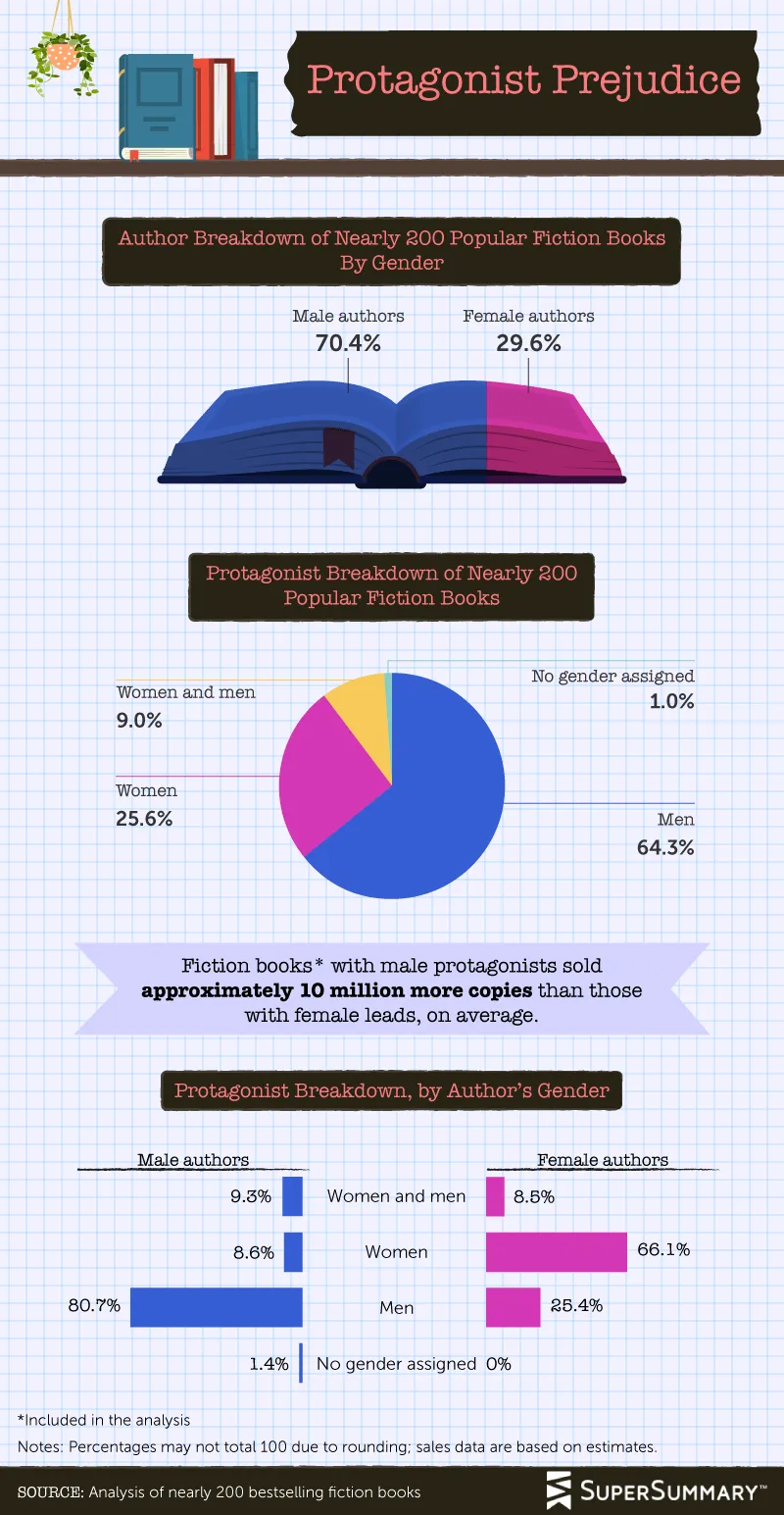

Starting with gender and popular fiction, it’s clear that the bulk of authors were male. The difference is pretty stark, too—over 70% of the bestselling books used in this study were by male authors, while only 30% were by women authors.

This breakdown isn’t too different in protagonist gender, either. The bulk were male (roughly 65%), with female protagonists at about 26%. The remaining percentage were books featuring both a male and female protagonist or a protagonist who has no stated gender.

Male authors tend to write male characters far more than female, while female authors tend toward female characters, though over a quarter of those bestselling books by women writers did feature male characters. It’s hard not to see how the influence of growing up in a culture that worships the “classics”—typically books by white men—sets the standard for what a preferred character type is. Ingrained sexism is another likely explanation for why it is women are more comfortable writing male characters while male writers who write female protagonists do so at a far lower percentage.

What’s most noteworthy, though, is that books with male protagonists sold an average of 10 million more copies than those with a female protagonist.

Not all books by male authors failed the Bechdel Test. But again: the Bechdel Test is an extremely simple, straightforward measure of sexism in books.

None of the books listed under those which fail the Bechhdel Test are especially surprising—with the exception of The Life of Pi, all of these titles were published prior to 2000. They also tend to follow the Hero’s Journey formula, notorious for not being especially applicable to stories where women are at the center.

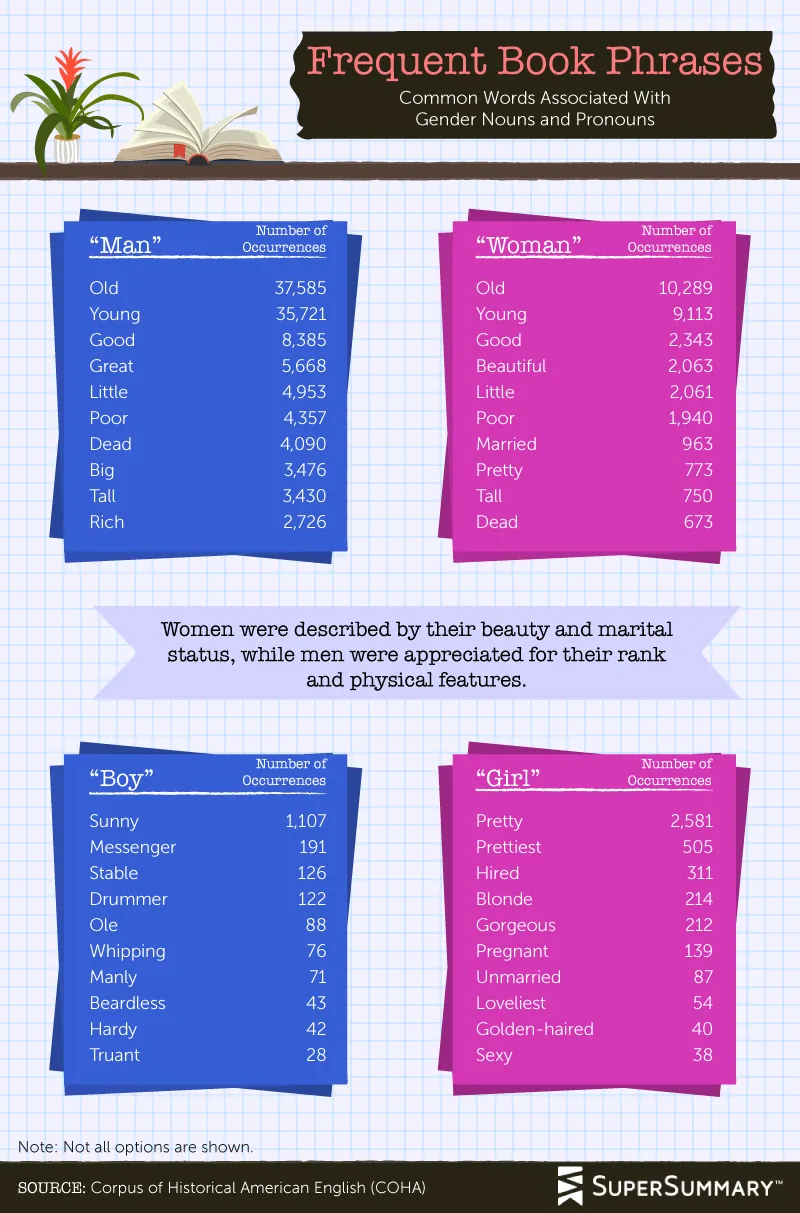

SuperSummary explored the descriptions used as they relate to gender nouns and pronouns.

Some of the noteworthy points here include that women tend to be described as “married”—this doesn’t even show up in the top ten lists for male characters—and when it comes to descriptions for boy and girl, “unmarried” shows up for girl, as does pregnant, sexy, and “golden-haired,” while none of those show up for boy. Interesting, “Whipping” and “Drummer” and “Ole” show up for boy, all of which are terms connected to common English sayings like “Good Ole Boy,” “Dummer Boy,” and “Whipping Boy.” The only straightforward physical description of boy is “beardless.”

A few other noteworthy finds from the breakdown of descriptions and gender:

- The pronoun “his” was more likely to be paired with nouns that denoted status and power: “Lordship” was the most common, appearing 1,789 times, followed by “disciples” and “excellency.”

- The pronoun “her” was most likely to be paired with domestic duty nouns, such as sewing (792 appearances), while “ladyship” and “boyfriend” trailed behind.

- The male “hero” was most often described as “great,” “national,” and even “old,” while the “heroine” was “little,” “new,” or “beautiful.”

It should come as zero surprise, then, given the information above, as well as general knowledge of how pervasive sexism is, that descriptions for women relied heavily on marital status and their appearance, while those for men were far more about their rank and power.

Men were simply described more than women were, except in terms of physical attributes. Though it’s not addressed in the study, it would be fascinating to see how many of the male-authored books with female protagonists relied on physical descriptions more than others.

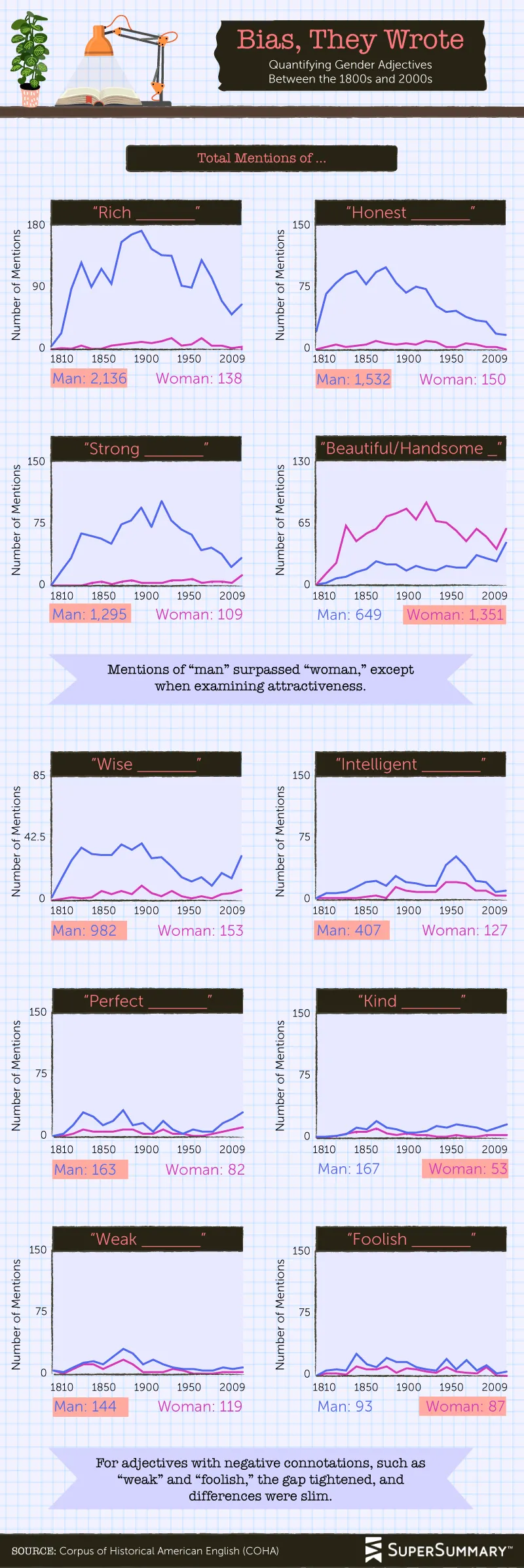

The above charts are fascinating less for their charting of descriptions as they relate to man and woman and more for how those words were distributed over time. “Intelligent” as a descriptor hit a peak in the 1950s but hasn’t seen a sharp rise again since. Both “beautiful” and “handsome” are having a renaissance in today’s bestselling fiction, while “honest” has fallen steadily since its peak in the late 1800s.

Women don’t get to be rich, it seems, and more, while men are seeing their richness grow in today’s bestselling fiction, women can’t be so lucky.

SuperSummary’s research is fascinating because of how it puts to use the tools out there together. Though this study is far from academically rigorous, and it certainly falls short in its controls and exploration of diversity (chances are Black women and Latina women are depicted in wholly different ways than the golden-haired white women), it confirms what has been assumed for a long time: despite women “dominating” publishing, their stories sell far less than those by male peers, are told far less frequently by men, and don’t permit them the same opportunities to be rich and powerful.