Maiming or Claiming?: On Writing in Books

WARNING: Contains explicit scenes involving the manhandling of books.

Jeanette Solomon’s adorable rules for reading reminded me of one summer day when my son had just returned home from college; he had picked up my copy of Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s Ghost. I was in the kitchen, and he came to me with a look of deep concern. In a small, sad voice he said, “Momma? Why? Why did you fold down these corners?”

I paused, distracted, wondering how to respond, and in that moment of hesitation, he began methodically unfolding the dog-eared corners.

I panicked. “Stop! I have to do it! I want to remember… a beautiful sentence or a scene or….”

He stared at me, seemed to deflate, and then walked away in silence.

Looking at any of my son’s books, you would never be able to tell whether they had been read. Mine, not so much.

I don’t have rules, but I have cultivated reading habits—dog-ears, for sure. And I religiously write in books.

On the first page or so I record the date I started reading (month and year), and why I picked that title—for instance, if it was a gift or recommended by someone, or an author I found mentioned in another book, or an author I heard speak. If I’ve heard a lecture by that author, I typically leave a program tucked inside. Sometimes I’ll record where I picked up the book, if I’m especially tickled by my find: Port Townsend Goodwill, $1.99, no kidding! or Epic Road Trip, Winona, MN, June 2014.

And that’s the bare minimum.

In some books I use a system of arrows, circles, exclamation points, stars, checks, etc., for the text itself.

(Side note: When I asked my son to look through this post, he confessed that he didn’t remember the dog-ears in Anil’s Ghost because evidently I had written an exclamation point in the margins by a sex scene—which I do not remember at all. “That was uncomfortable.” Moral? Administer exclamation points with caution.)

Arrows and whatnot help me remember and connect ideas in the same way that taking notes would.

But my fondest treasures are the marginalia recording details about where I was when I was reading, vignettes, tableaux.

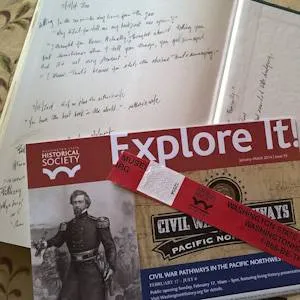

A couple years ago, I had twenty pages left of his terrific Civil War novel Wilderness when went to hear local author Lance Weller speak at our history museum. On the end papers, I took notes. Before I knew she was his wife, a smiling woman timidly said to me, “You have the best book in the world.” I had remembered only a vague sense of how very sweet and loving the author and his wife had been with each other until I looked at my notes. I had forgotten her endearing proclamation.

Just the day before, my younger son Seth and I went to the zoo so he could finish up an assignment for his high school biology class. I sat reading Wilderness while he did his observing and note-taking and whatever else. According to my notes, I was in a sunny spot by the seals when a small girl came tearing around a corner ahead of her family. She saw me and stopped dead. She looked at me a moment, perfectly still, then turned to looked back at her mum, and asked, “Is she a part of the zoo?”

Other highlights in the margins include Seth, muttering after a father walked by with a collection of tiny children, “Three girls. All close in age. That would be… a nightmare.”

And evidently the lemurs had broken into an almighty roar, fighting, just as we were approaching their enclosure. I was a little rattled by the din until Seth turned to me with a wry grin, and casually remarked, “And they look like such cute little things!”

“It was sunny with occasional spitting rain and steady wind. The crows kept up their constant rowdy chorus. Like they do.”

It was a good day. And hints about that one ordinary day are hidden in a nondescript book on my historical fiction shelf.

On a different spring morning, “steady rain,” I was sitting in a coffee shop reading Michael Sims’ book The Adventures of Henry Thoreau. A fella came in and sat at the next table, facing me. He was wearing motorcycle boots, a red plaid shirt, with sleeves rolled up, and Carhartt work pants. His beard trembled as he whispered, hunched over a pile of loose pages—he was memorizing lines from King Lear.

Later, that week, at home, snuggled up reading together, I shared with my son a tidbit I’d learned about cannonballs being standard issue for Harvard students, back in Thoreau’s day, something to do with heating. Those naughty boys would then set the things rolling down the stairs in the middle of the night.

“Did you learn that in Sims’ book?” “Yes.” “Stop telling me everything! You’re giving away all the good parts and I want to read it myself!” “…” “Mother! Are you writing that down?!”See, there is a kind of magic that happens when we read a book. We don’t merely enter another world, but that world enters us, marks us. It seems appropriate to record the intersection, the details that make up the context of our reading. While my boys have finally stopped shouting “BLASPHEMY!” whenever they see me taking notes, I know they still merely tolerate, and do not approve. They may never appreciate my palimpsest offerings, but eventually, when I am gone, perhaps my grandchildren will enjoy catching a whiff of this life. If nothing else, the titles on my shelves will indicate something about the quirky life of this mind. And inside those books, they will see my delight, in the texts themselves, in my own children, and the world around me.