Let’s Get Messy: Literary Beefs and Rivalries

Since late March, I’ve been following a rap beef that situated Drake against Future, Metro Boomin, and Kendrick Lamar. While it seemed standard at first, it took a turn. Soon, it became just Kendrick vs. Drake, and the insults being thrown around were serious. Among other things, Kendrick called out Drake’s tendency to appropriate Black American culture and accused him of being a misogynist and an abuser.

And Kendrick mopped the floor with him.

Never before have I seen such a huge star be taken down so swiftly and so absolutely. All up and down my TikTok timeline, I saw people quoting different parts of Lamar’s four diss tracks, and, over the Cinco de Mayo holiday, so many videos were made of people dancing to “Not Like Us,” with its driving West Coast beat and quotable, heavy-hitting punchlines. News of the beef even reached the non-hip-hop mainstream, and everyone from The New York Times to The Guardian had something to say about it.

But what does this have to do with literature?

Well, if you belong to the camp that sees music lyrics as literature, the answer to that is obvious. For everyone else, oral traditions go back further than written ones, for one; and poetry, which a lot of rap is, has a rhythmic quality that lends itself to being spoken aloud. Bob Dylan has won a Nobel Prize, and Kendrick Lamar, slayer of Canadian rappers, won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for his album DAMN.

All together, this beef has been such an interesting moment in Black American culture, and it feels like a turning point for pop culture overall. Even so, there are those who’ve tried to downplay it. There are plenty of posts across social media platforms that try to shame those of us who have been watching it unfold, and there’s even a Rolling Stone article that whines about how hard it is to “care about a rap war in the middle of a real one.” As if we can’t walk and chew gum at the same time.

Hip-hop is a huge part of Black American culture, so when I see sentiments like these, and remember how there are efforts to preserve other cultures’ art during chaotic times (like how The Getty gave $1 million to help Ukraine store art during the war), I recognize them for what they are: subtle ways to invalidate Black American culture.

With all of that said, the beef isn’t without its problematic moments. At times, both Kendrick and Drake lobbed jabs at each other, which reduced women’s and girls’ trauma to punchlines. It’s this relegation of Black women’s concerns to the background and the aforementioned invalidation of Black people and our culture that I wanted to touch on in the first couple literary beefs I highlight.

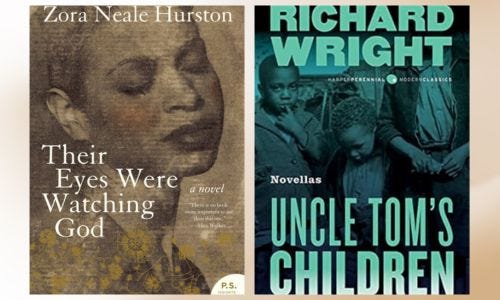

Richard Wright vs. Zora Neale Hurston

Richard was the one to throw the first literary jab in this beef.

In 1937, Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God — what would become her most well-known work — was published.

And then, Wright’s messy self threw himself in the mix.

He wrote an essay decrying Hurston’s book, essentially saying how its focus on the Black female main character’s quest for self-actualization — which included her sex life — played into stereotypes surrounding Black people and promiscuity.

He said it had, “no theme, no message, no thought. In the main, her novel is not addressed to the Negro, but to a white audience whose chauvinistic tastes she knows how to satisfy.” He equated its lack of Black rage as a minstrel act on the page and even said that her writing had a “facile sensuality,” something that had — according to him — first taken root in Black writing courtesy of Phillis Wheatley, another Black woman literary star. He says all this despite the fact that one of his most well-known novels, Native Son, follows a young Black man, Bigger Thomas, who killed a white woman, and whose name…is a choice. Yeah.

A year later, Hurston, as petty as ever — and rightfully so — reviews Hurston Wright’s first book, Uncle Tom’s Children, saying “There is lavish killing here, perhaps enough to satisfy all male Black readers.” Whew.

This feud perfectly encapsulates the issue of sexism within Black culture and directly shows the need for Kimberle Crenshaw’s coining of the term “intersectionality.” The time Hurston and Wright were most active — during the Harlem Renaissance — was a time that Black creatives were struggling against not feeding into negative stereotypes surrounding Black people, and expressing themselves authentically. Tiktoker TjMartinsonWritesBooks contextualizes this well, and I wrote about why Cane by Jean Toomer was so influential during this time.

It was this need to counteract these negative stereotypes that had some Black folk engaging in respectability politics, especially — and in some cases, exclusively — as it pertained to women. We see this with Richard Wright, who had no problem with writing books that contained negative stereotypes but drew the line at Black women writing about their experiences authentically.

Toni Morrison vs. Bill Moyers

This is less a two-sided beef and more Moyers just showing his ass while Morrison displays saintly patience.

When she was interviewed by him in 1990, he asked her if she could ever write a book that didn’t center Black people. As I mentioned before, her response was graceful. Still, eight years later, she was asked about the Moyers interview by Charlie Rose, and she explained how Moyers’ question was rooted in eurocentrism, and how utterly othering it was.

So close, in fact, that they even courted the same woman, the popular Florence Balcombe. This is partially where the beef started. At first, Wilde and his enticing flamboyance had Balcombe’s attention, but then Stoker proposed — rather scandalously — and she ended up marrying the more square Stoker instead.

Later, when Wilde was sent to jail for two years for being queer, Stoker started working on Dracula. Book Riot writer Tika Viteri noted how Stoker describes the character Dracula the same way Wilde is described by the public. Each one is an “overfed leech,” and exemplifies the ills of society.

Salman Rushdie vs. John Updike

In 2006, John Updike wrote a review for Shalimar the Clown by Salman Rushdie, and had thoughts. Specifically, on Rushdie’s name choice for one of the book’s characters. He asked “Why, oh why, did Salman Rushdie, in his new novel, Shalimar the Clown, call one of his major characters Maximilian Ophuls? Readers of this review will be spared, as the reviewer was not, the maddening exercise of trying to overlay Rushdie’s Ophuls with the historical one. The two have no connection save the name and a peripatetic life.”

Then, Rushdie, in all his pettiness, replied “‘Why, oh why. . . ?’ Well, why not? Somewhere in Las Vegas there’s probably a male prostitute called ‘John Updike’.” Sir!

Continuing, he said “The thing that disappointed me most about Updike is that he did not say in that review that he had just completed a novel about terrorism. He had to sweep me out of the way in order to make room for himself. I don’t subscribe to the very predominantly English admiration of Updike…He should stay in his parochial neighbourhood and write about wife-swapping, because it’s what he can do.”

Gabriel García Márquez vs. Mario Vargas Llosa

This is reality show-variety beef. Vargas Llosa cheated on his wife with a Swedish stewardess. Then Patricia, his wife, goes to Vargas Llosa’s best friend, García Márquez, for advice. He suggests divorce…and maybe something else. A certain kind of something else leads to Vargas Llosa hitting García Márquez with a two-piece the next time he sees him in Mexico City in 1976. A day later, García Márquez and his wife, Mercedes, go to their friend Rodrigo Moya’s place and García Márquez asks him to take a picture of his black eye. Moya said, “He look[ed] like he was really beaten up, like beaten up by the Mexican police.” A whole mess.

Trust me when I say that there are many more literary beefs — like the one between Colson Whitehead and Richard Ford (there’s spit involved!), and Ernest Hemingway and, like, all of his contemporaries — but I hope my little foray into literary scandal satiated the messiest corners of your heart.

The comments section is moderated according to our community guidelines. Please check them out so we can maintain a safe and supportive community of readers!

The comments section is moderated according to our community guidelines. Please check them out so we can maintain a safe and supportive community of readers!

Leave a comment

Join All Access to add comments.