On Jules Feiffer’s KILL MY MOTHER

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Like many readers in my generation, my first exposure to the work of Jules Feiffer was not through Kill My Mother, but through the perennial children’s classic, The Phantom Tollbooth, a book that speaks as loudly to the modern, lamentable (and easily escapable) ennui of childhood today as it did at its original publication in 1961. Of course, Feiffer is best known as a satirical/political cartoonist, one who won numerous awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, during a half-century of cartooning.

Five decades of political cartooning, prodding and penetrating the American psyche to examine its anxieties, neuroses, and socially constructed assumptions, would be enough of an accomplishment for a lifetime. (I personally turned my hand to political cartooning after the last presidential election, and burned out in the space of about four months; I still had plenty to say, but my soul couldn’t handle the burden of saying it cogently, day after day.) In addition to cartooning, Feiffer wrote a number of books for children, illustrated numerous books written by others, and produced a quantity of novels and scripts, many of which he created after his “retirement” in 1997.

Like many readers in my generation, my first exposure to the work of Jules Feiffer was not through Kill My Mother, but through the perennial children’s classic, The Phantom Tollbooth, a book that speaks as loudly to the modern, lamentable (and easily escapable) ennui of childhood today as it did at its original publication in 1961. Of course, Feiffer is best known as a satirical/political cartoonist, one who won numerous awards, including a Pulitzer Prize, during a half-century of cartooning.

Five decades of political cartooning, prodding and penetrating the American psyche to examine its anxieties, neuroses, and socially constructed assumptions, would be enough of an accomplishment for a lifetime. (I personally turned my hand to political cartooning after the last presidential election, and burned out in the space of about four months; I still had plenty to say, but my soul couldn’t handle the burden of saying it cogently, day after day.) In addition to cartooning, Feiffer wrote a number of books for children, illustrated numerous books written by others, and produced a quantity of novels and scripts, many of which he created after his “retirement” in 1997.

In my life as a literacy advocate for elementary students, I have shared many of Feiffer’s picture books with young readers, and his sense of joy and comedy are not watered down even as his work explores the same themes of ridiculousness and reality that features in his adult material. In Bark, George, a puppy defies expectations by making every animal noise except for the one representative of his species. In By the Side of the Road, a child peacefully overcomes his father’s anger by refusing to participate in their family dynamic, opting to instead create his own idyllic utopia by the side of the road. The give and take of relationships—familial, romantic, and everything in between—is his constant theme.

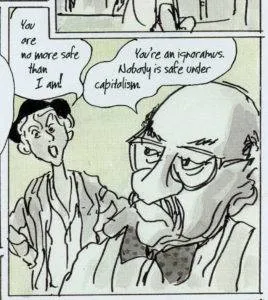

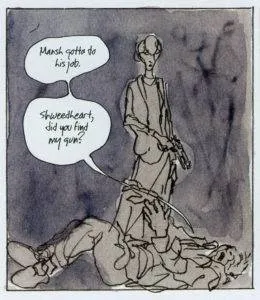

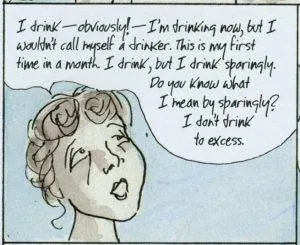

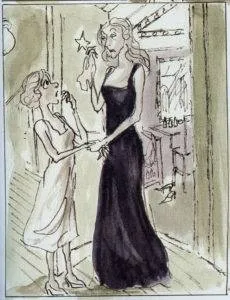

Feiffer’s artwork is deceptively simple. He began his career as an assistant to Will Eisner, who considered Feiffer a mediocre artist with other impressive qualities. Feiffer’s lines appear dashed out without consideration to style or gravity anything beyond what works, and yet he conveys the full spectrum of human experience with these simple, shaky, meandering ink marks. When his characters dance joyfully, those scratches convey a sense of being lighter than air. When his characters hang their head in dejection, you can almost calculate the actual weight of the world upon their shoulders. With a very few brushstrokes, he describes the illusion of life, such that the reader nods their head and says, “Yes, this is what people are like,” even though, from close up, his reality is only a fortunate confluence of scribbles.

In my life as a literacy advocate for elementary students, I have shared many of Feiffer’s picture books with young readers, and his sense of joy and comedy are not watered down even as his work explores the same themes of ridiculousness and reality that features in his adult material. In Bark, George, a puppy defies expectations by making every animal noise except for the one representative of his species. In By the Side of the Road, a child peacefully overcomes his father’s anger by refusing to participate in their family dynamic, opting to instead create his own idyllic utopia by the side of the road. The give and take of relationships—familial, romantic, and everything in between—is his constant theme.

Feiffer’s artwork is deceptively simple. He began his career as an assistant to Will Eisner, who considered Feiffer a mediocre artist with other impressive qualities. Feiffer’s lines appear dashed out without consideration to style or gravity anything beyond what works, and yet he conveys the full spectrum of human experience with these simple, shaky, meandering ink marks. When his characters dance joyfully, those scratches convey a sense of being lighter than air. When his characters hang their head in dejection, you can almost calculate the actual weight of the world upon their shoulders. With a very few brushstrokes, he describes the illusion of life, such that the reader nods their head and says, “Yes, this is what people are like,” even though, from close up, his reality is only a fortunate confluence of scribbles.

The scratched-out cartoon style sits in contrast to Feiffer’s language, the medium through which he describes his understanding of his true interest: human nature. In 2014’s stunning Kill My Mother, Feiffer births a cast of characters as cartoonish in appearance but as real in nature as a reader could desire, and drops them into a hardboiled, Raymond Chandler-style narrative. Annie, the irrepressible teenage delinquent, happily blames her anger and her anti-social behavior on the fact that her single mother has a job. Elsie, the harried widow, is willing to put up with every form of physical danger and sexual harassment if it means catching her husband’s killer. Dorothea, tall and imposing and terrified, forsakes speech even as her heart demands that she sing. Even the drunk detective, the hired hit man, and the fleet footed boxer, seeming stock characters from central casting, take on real life in Feiffer’s knowing hands.

The scratched-out cartoon style sits in contrast to Feiffer’s language, the medium through which he describes his understanding of his true interest: human nature. In 2014’s stunning Kill My Mother, Feiffer births a cast of characters as cartoonish in appearance but as real in nature as a reader could desire, and drops them into a hardboiled, Raymond Chandler-style narrative. Annie, the irrepressible teenage delinquent, happily blames her anger and her anti-social behavior on the fact that her single mother has a job. Elsie, the harried widow, is willing to put up with every form of physical danger and sexual harassment if it means catching her husband’s killer. Dorothea, tall and imposing and terrified, forsakes speech even as her heart demands that she sing. Even the drunk detective, the hired hit man, and the fleet footed boxer, seeming stock characters from central casting, take on real life in Feiffer’s knowing hands.

Details jump from the page in Kill My Mother. There are the faint hints of blue and green watercolor washing over a mainly black and gray book, adding surprising visual highlights behind the ink flourishes. There are the spoken details. Strong-arming her milquetoast boyfriend into shoplifting, Annie says, “Think about it, Artie—who’d you rather be in trouble with? The store? Or me?” And the details of characterization, strong and comic but believable at every turn, even when minor characters only appear for a few pages, like the communist liquor store owner who begrudgingly uses the tactics of capitalism when it suits him. As for the particulars of the murder mystery, again, despite its unusual and almost comic solution, the reader again can’t help but think, “Yes, this is what people are like.” Even the less-mysterious murders and attempted murders that occur with increasing frequency throughout the book take place in that believable intersection between human nature and human irrationality.

Humans are ridiculous, and flawed, and lovable, and capable of feeling and acting upon vast and intense love, often in ridiculous and flawed ways. Yes, this is what people are like, and for seventy years, Jules Feiffer has worked to show this understanding to the rest of us through works like Kill My Mother.

Details jump from the page in Kill My Mother. There are the faint hints of blue and green watercolor washing over a mainly black and gray book, adding surprising visual highlights behind the ink flourishes. There are the spoken details. Strong-arming her milquetoast boyfriend into shoplifting, Annie says, “Think about it, Artie—who’d you rather be in trouble with? The store? Or me?” And the details of characterization, strong and comic but believable at every turn, even when minor characters only appear for a few pages, like the communist liquor store owner who begrudgingly uses the tactics of capitalism when it suits him. As for the particulars of the murder mystery, again, despite its unusual and almost comic solution, the reader again can’t help but think, “Yes, this is what people are like.” Even the less-mysterious murders and attempted murders that occur with increasing frequency throughout the book take place in that believable intersection between human nature and human irrationality.

Humans are ridiculous, and flawed, and lovable, and capable of feeling and acting upon vast and intense love, often in ridiculous and flawed ways. Yes, this is what people are like, and for seventy years, Jules Feiffer has worked to show this understanding to the rest of us through works like Kill My Mother.