The “Joke” of THE KILLING JOKE

Batman: The Killing Joke

Alan Moore: Writer

Art and Colors: Brian Bolland

Letterer: Richard Starkings

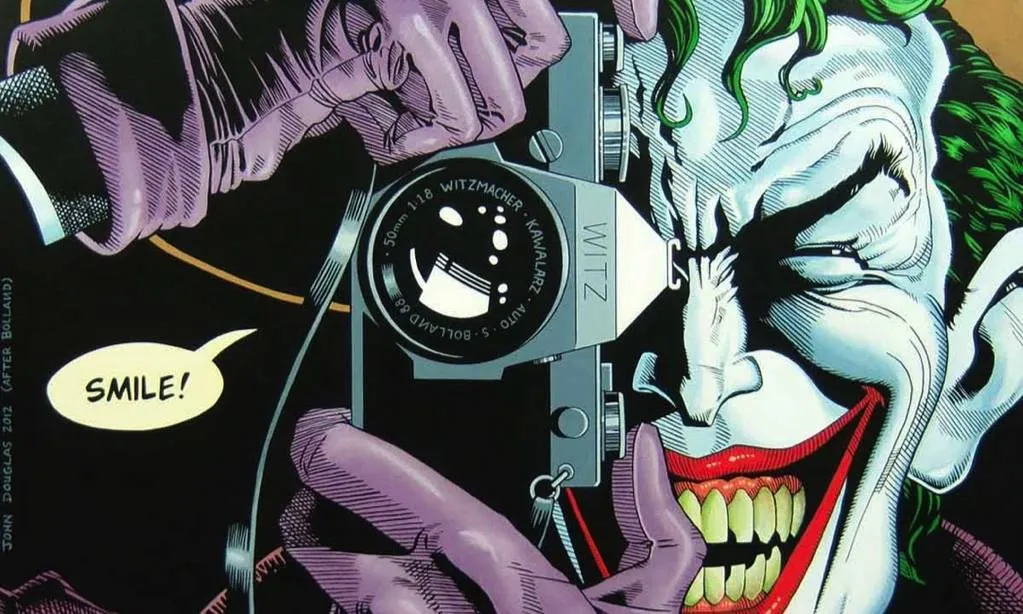

See, there were these two guys in a lunatic asylum… and one night, one night they decide they don’t like living in an asylum any more. They decide they’re going to escape! So, like, they get up onto the roof, and there, just across this narrow gap, they see the rooftops of the town, stretching away in the moon light… stretching away to freedom. Now, the first guy, he jumps right across with no problem. But his friend, his friend didn’t dare make the leap. Y’see… Y’see, he’s afraid of falling. So then, the first guy has an idea… He says “Hey! I have my flashlight with me! I’ll shine it across the gap between the buildings. You can walk along the beam and join me!” B-but the second guy just shakes his head. He suh-says… He says “Wh-what do you think I am? Crazy? You’d turn it off when I was half way across!Batman laughs because this joke illustrates his life, his struggle with the Joker, his identity as a superhero. Both characters exist in a fantasy. They may not be “not like any humans that ever lived” in their personal expression, but they are the perfect example of a shared delusion. They’ve created their world together. They both believe in the bridge of light, but Joker doesn’t believe in redemption, and inexplicably, Batman does. More than ten years after he wrote The Killing Joke, Moore has Aleister Crowley tell an ideologically similar joke in Promethea Book 2, chapter 6. Two strangers, one of whom carries a box punched with air holes, share a railway carriage. The second stranger asks what’s in the box. The first stranger explains that it’s a mongoose he’s bringing to his mentally ill brother, who is plagued by visions of serpents. “These snakes your brother sees…aren’t they imaginary snakes?” asks the second man. “Indeed,” says the first, “but this…is an imaginary mongoose.” According to Moore, if you understand this joke, you understand magic. The world, magic tells us, is precisely what we make it. What we believe, we manifest. There’s no sense in arguing about what exists; you fight delusion with delusion. Reality is psychosomatic. One of the things that people love about The Killing Joke is that it offers an origin story for the Joker, who never gets a definitive origin story. Maybe that’s what’s so scary about him. The Joker is so insane, and so obsessed with driving other people nuts, and we don’t know why. And the book also focuses on the Joker’s idea that sanity is this tenuous, that we’re all “one bad day” away from becoming homicidal lunatics. Except, of course, Batman has “one bad day” and it turns him into Batman (lunatic, yes, homicidal, no) and, in the course of the story, Jim Gordon has “one bad day” and it strengthens his resolve to be Jim Gordon: “You have to go after him! I want him brought in…and I want him brought in by the book!” The Killing Joke draws a very human Joker, and a very human Batman. Batman, terrified that the Joker’s antics will turn him homicidal, offers another way. “I could rehabilitate you,” Batman says. “You needn’t be alone.” This is the joke. Batman, teaching the Joker sanity, is like an escaped mental patient offering another escaped mental patient a bridge made out of light. A lot of readers argue that the book ends with Batman killing the Joker, but I disagree. The joke’s not funny if Batman stops believing in the bridge. He says multiple times that he doesn’t want to hurt the Joker. He needs the Joker, to remind him who he is. To me, when Batman reaches for the Joker, they are sharing a human moment, acknowledging that they’re in this together. They could both be in Arkham Asylum; they could both be in the Bat Cave. But they’ve chosen sides. They’ve chosen identities. Another thing this book does differently from a lot of Batman stories is acknowledge that Batman and the Joker not only need each other, but in fact, created each other. Joker becomes the Joker when he jumps into chemical waste to escape “that human bat guy, in all the papers lately.” Batman recognizes that his decades-long struggle with this criminal defines him. They’ve constructed their realities together as two men who oppose each other, much in the way that rebellious teenagers create identities based on the opposite of their parents’ values. That’s the joke. The bridge of light is real because the lunatics believe it’s real. Batman is Batman because he believes in Batman. Joker is Joker because he believes in the Joker. Jim Gordon is Jim Gordon because…well, you get the picture. We get to choose.