Share This Link 9 Times or Never Read a Good Book Again!

“I’m looking for people to participate in a huge book exchange. You can be anywhere in the world. All you have to do is buy your favorite book (just one) and send it to a stranger (I’ll provide their details through a private message).

You’ll receive a roughly maximum of 36 books back to you, to keep. They’ll be favorite books from strangers around the world.

If you are interested in taking part, please comment ‘IN’ below and I’ll send you all the details.”

You’ve likely seen this message (errors and all), or one like it. Maybe it was in a letter in 2018. Or on Facebook in 2020. Or Instagram in 2022. This sort of book exchange scheme pops up every few years, each promising that you can get about 36 books just by mailing out one. As you’ve probably guessed, it doesn’t usually work out like that. It’s a pyramid scheme: the people who get in early might come out fairly successful, but the majority of people will end up with no books at all. As a Canadian, I find this one particularly distasteful: it costs about $15 just to ship within the country here, so buying a new book and sending it overseas could be about a $50 commitment, which is steep for something that has a good chance of not returning any investment at all.

I’ve been fascinated with chain letters for years, partly because of their staying power. They evolve with every new technology, staying relevant over centuries. We can trace them back almost as far as writing, and I wouldn’t be surprised if oral stories with some “tell five people or be doomed for all eternity” element were told before that.

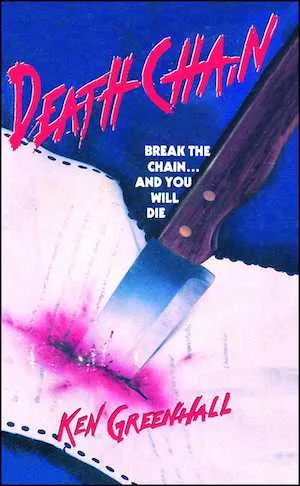

Chain letters have inspired books and movies, mostly of the murder mystery or horror variety. There’s Chain Letter by YA horror author Christopher Pike — not to mention Chain Letter 2: The Ancient Evil — and Deathchain by Ken Greenhall, whose cover promises, “Break the chain…and you will die.” Claire McNab and Ruby Jean Jensen both have mysteries that share the title “Chain Letter.” A horror movie in 2010 is titled “Chain Mail,” and The Ring — based on the book Ring by Koji Suzuki — is essentially a chain letter in VHS form. Although chain letters can be used for inspiration, charity, or profit, we clearly associate them with their more nefarious variety, which threaten death to anyone who would break the chain.

Chain letters are the original meme. They exist to be passed on, and they often change along the way. But although sharing them can come from a desire for community or optimism about their potential, they can also be dangerous. Chain letters, pyramid schemes, and Ponzi schemes all have the same DNA, and sometimes they are one and the same. It’s perhaps not surprising they saw a surge in popularity during both 2020 and the Great Depression. They offer an illusion of control, which is attractive when you feel powerless.

Let’s take a look back in time to see where chain letters began, and how they keep copying themselves even today, promising luck, money, and even books.

A Brief History of Chain Letters

It’s hard to nail down the first chain letter because it depends on the exact limits of your definition. The Egyptian Book of the Dead promises that anyone who copies the image “shall find it of great benefit to him both in heaven and on earth.” The “man who knows not this picture shall never be able to repulse the serpent Neha-hra.” A medieval version of a chain letter claimed to be authored by Jesus himself: “He that copieth this letter shall be blessed of me. He that does not shall be cursed.”

Of course, for chain letters to really take off, they needed more people to be able to both read and write — and a reliable postal service helped. Snopes puts the first “full-fledged” chain letter in 1888, which was used to raise money for charity. A 17-year-old Red Cross volunteer started a similar letter in 1898 to raise money to buy ice for troops in Cuba, which soon flooded a tiny Babylon, N.Y. post office with thousands of letters, prompting her mother to put out a statement urging people to stop sending money. These early versions were very successful, with a benefiting school proposing it as a long-term fundraising strategy: the “peripatetic contribution box.”

It didn’t take long for these promising money-making strategies to be turned into more selfish motivations. By 1917, a New York Times article accused chain letters of being a German plot to clog the postal service. (It’s charming now to imagine the post office getting too much business as their biggest hurdle.) In 1922, a scathing Saturday Evening Post editorial asked if chain letter participants realize that a completed “chain” would require 3.5 billion people, $70 million in postage, and several forests’ worth of paper. “[T]heir common sense appears to be urgently in need of an injection of either monkey or goat gland,” the author continues.

The height of chain letters’ popularity was in 1935, with the “Send-a-Dime” scheme. This chain letter was so popular that stores selling certificates to prove you were “officially” on the chain popped up in empty storefronts. One had over 100 employees when it was shut down! After a few weeks, the Send-a-Dime chain collapsed: there was no one to send a letter to that wasn’t already in the chain, and the postal service had declared it violated lottery laws. By July, it left “between 2,000,000 and 3,000,000 letters in the dead letter offices” — and those were just the undelivered ones! The popularity of the Send-a-Dime letters spurred spin-offs, like whiskey chain letters, as well as parodies, like a “send a Packard Automobile” letter, which said, “Think how nice it would be to have 15,625 automobiles.”

The photocopier’s invention in 1959 made chain letters popular again, because they were much easier to reproduce. The invention also changed them: there were fewer “mutations” in letters, like a man losing his life after breaking the chain turning into losing his wife in later iterations. These photocopied chain letters stayed pretty much identical in their whole run.

The next big chain letter get rich quick scheme was in 1978, with the “Circle of Gold” letter. This was the same idea as the Send-a-Dime scheme, but instead of 10 cents, you had to sent $50 to the top person on the list and $50 to the person who gave you the letter. With a list of 12 people on each letter, it promised to make you $100,000. It was also hand-delivered, to avoid being stopped in the mail. It started in San Francisco and made its way across the country to New York City, even appearing in Hawaii. In the end, some people claimed to make $30,000, but most people were out $100.

In the 1990s and 2000s, chain letters took on a different form as forwarded emails. These iterations weren’t usually money-making strategies or ominous threats; the ease of passing them along meant they were more likely to be silly entertainment or recipes than elaborate pyramid schemes.

Chain Letters Today

Centuries later, chain letters are still flourishing. Even the money-making schemes are still circulating: 2015 saw a “Silent Sister” chain on Facebook that promised 36 gifts if you have $10 to the person at the top of the chain. A Washington Post article found that if this chain ran uninterrupted for two weeks, it would required everyone on Earth to participate 11 times.

Chain letters persist on Facebook today, just as they were popular on Tumblr in recent years. In fact, reactionary “protective image” posts also circulated on Tumblr, promising immunity from the bad luck of breaking a chain letter.

The most popular platform for chain letters now, though, isn’t text-based at all: it’s TikTok. Chain letter TikToks urge you to share or use the video’s sound to avoid bad luck. Superstitious users will soon be caught in a loop, because the algorithm will keep offering them more chain letter content if they interact.

While so many of us were stuck inside during the early months of the Covid-19 pandemic, chain letters saw a resurgence of popularity, mostly in the form of uplifting messages and recipe chains.

Emoji-filled text chain letters are also a popular format — some of them definitely not safe for work, and some of them more closely replicating old threatening paper chain mail. A recent Slate advice column asked for guidance in what to do about her teenager daughter making up creepy chain letters and sending them to friends.

The more I looked into chain letters, the more I began to see them everywhere. In an April 2023 interview, Warren Buffett compared bitcoin to chain letters. Is blockchain just an automated chain letter?

Whether it’s a book distribution strategy, a get rich quick scheme, or just a way to pass the time, chain mail — whichever form it takes — does not seem to be going away over time. My advice? Don’t gamble away your book buying budget on the next book exchange chain letter. Just spend it on growing your own TBR.

Further Reading

These are the articles I found most useful when researching this post.

Smithsonian Magazine: “Before Chain Letters Swept the Internet, They Raised Funds for Orphans and Sent Messages From God” by Meilan Solly

Slate: “You Must Forward This Story to Five Friends: The Curious History of Chain Letters” by Paul Collins

Saturday Evening Post: “The Perpetual Annoyance of Chain Letters” by Jeff Nilsson

The comments section is moderated according to our community guidelines. Please check them out so we can maintain a safe and supportive community of readers!

Leave a comment

Join All Access to add comments.