A Guide to Sonnets

Of all the formal traditions in poetry, the sonnet might be the most famous. I blame Shakespeare. He wrote 154 of them that have been reprinted millions of times and famously read by the likes of Sir Patrick Stewart (and pretty much every other Shakespearean actor), but he didn’t write a guide to sonnets.

So what exactly is a sonnet? Where and when did it come from? What is the sonnet doing nowadays since ol’ Billy Shakes has been in his grave for over four centuries? Here’s a guide to sonnets.

Italian Beginnings

In the 13th century at the court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in Sicily, Giacomo da Lentini created the first sonnet. Derived from the Italian word sonetto, meaning “little song,” they were first used to express courtly love, but quickly took off and became predominantly used for expressions of romantic love.

The Italian sonnet doesn’t follow the same rhyme pattern you might know from Shakespeare. The Italian sonnet is divided into an octave (eight lines) followed by a sestet (six lines). The octave represents a problem while the sestet represents a solution or resolution. The octave always follows the pattern ABBA ABBA. The sestet is usually either CDE CDE or CDC CDC.

Sonnet 131 by Petrarch

I’d sing of Love in such a novel fashion

that from her cruel side I would draw by force

a thousand sighs a day, kindling again

in her cold mind a thousand high desires;

I’d see her lovely face transform quite often

her eyes grow wet and more compassionate,

like one who feels regret, when it’s too late,

for causing someone’s suffering by mistake;

And I’d see scarlet roses in the snows,

tossed by the breeze, discover ivory

that turns to marble those who see it near them;

All this I’d do because I do not mind

my discontentment in this one short life,

but glory rather in my later fame.

This earlier sonnet form also doesn’t follow the same meter as English sonnets. Early Italian sonnets didn’t have a standard meter and Petrarch (who made the form so famous that it’s also known at the Petrarchan Sonnet) used hendecasyllable lines, or 11 syllables per line.

This form grew so popular, and Petrarch with it, that it was difficult to find a romantic poem in the 14th or 15th centuries that wasn’t a sonnet.

The English Sonnet

This guide to sonnets continues to England. The Italian sonnet spread far and wide, seeing writers from all over Europe writing about romantic love with Petrarch’s chosen form. Many famous English poets such as John Milton, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and William Wordsworth wrote in the Petrarchan form. It was Thomas Wyatt who first wrote in what would be known as the English style.

In translating Petrachan sonnets from Italian and French, Wyatt adopted a rhyme scheme made of three quatrains (four lines) and one couplet (two lines): ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. Like with the Italian form, the volta (turn) of the poem occurs in line 9, marking a change in tone or a resolution. The English variant added a new twist in the final rhyming couplet, in which the poem is either summarized or looked back on in a new light.

Sonnet 106 by William Shakespeare

When in the chronicle of wasted time

I see descriptions of the fairest wights,

And beauty making beautiful old rhyme

In praise of ladies dead, and lovely knights,

Then, in the blazon of sweet beauty’s best,

Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow,

I see their antique pen would have express’d

Even such a beauty as you master now.

So all their praises are but prophecies

Of this our time, all you prefiguring;

And, for they look’d but with divining eyes,

They had not skill enough your worth to sing:

For we, which now behold these present days,

Had eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise.

The Modern Sonnet

The sonnet spread to nearly every country and language partly because as Shakespeare goes, so does the sonnet. There’s a reason it’s the one poetic form that almost everyone has heard of without any poetic training. It also means that like high schools performing Our Town, sonnets are so overdone that modern poets find it difficult to enjoy the form.

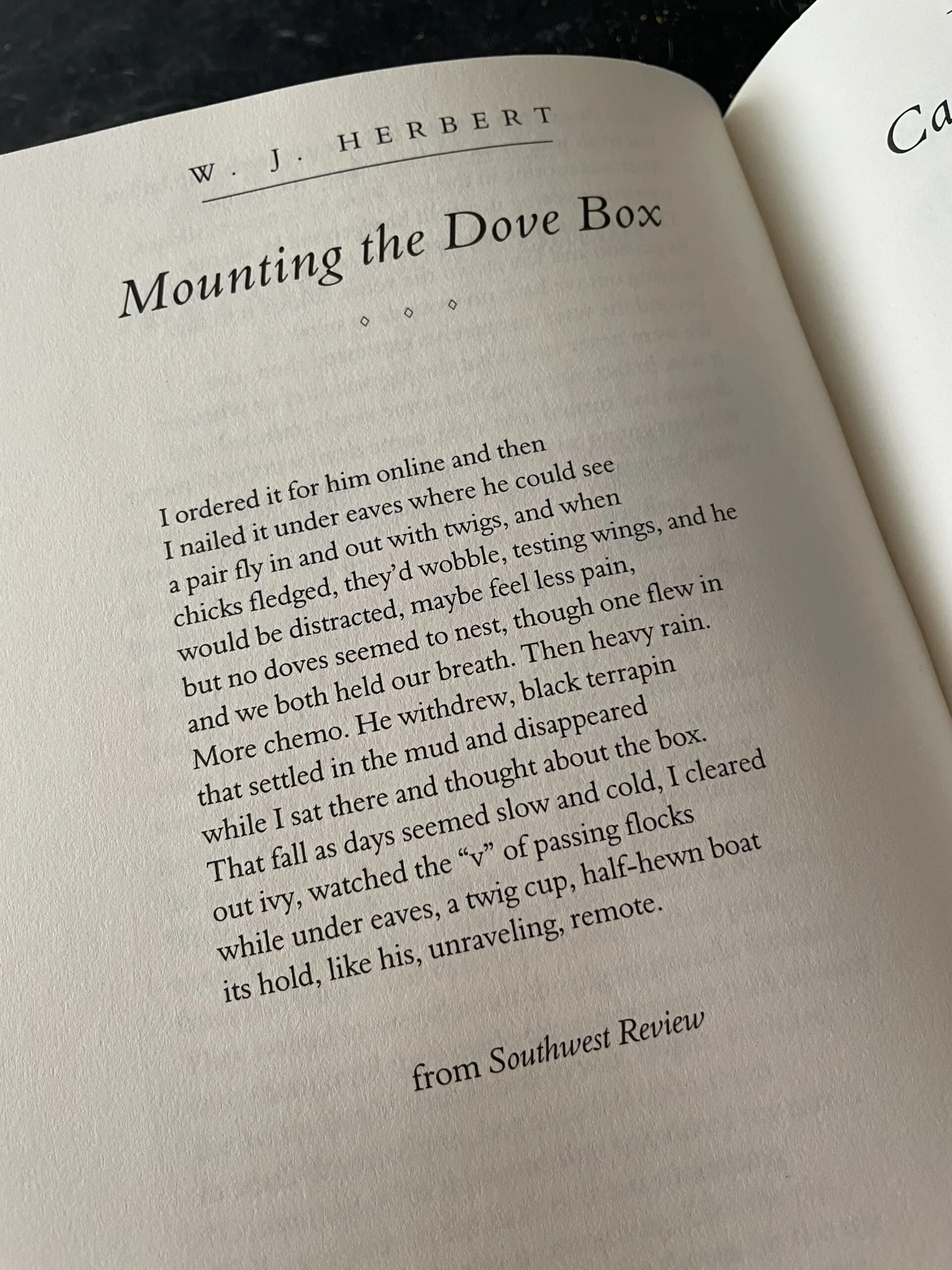

Nevertheless, the sonnet has a place in modern poetry. It’s a favored form of middle school poetry and Shakespeare classes. Every year since 2008, the River Arts Alliance has held the annual Maria W. Faust Sonnet Contest, inviting Shakespearean sonnet poets from several countries. 2020’s winners show just how far the sonnet has wandered from its romantic roots to take on modern sensibilities.

Most often, published poets use the form in full awareness of the history of the form and knowing that the reader’s knowledge of the history adds a layer of meaning to every sonnet. Such is the case with Terrance Hayes’s 2018 book, American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin. These 70 sonnets written in the first 200 days of Trump’s presidency explore the legacy and future of America in sonnet form, a form rooted in colonialism and white men.

In the hands of everyone from amateurs to National Book Award winners, the sonnet still finds life and love today. Give it a try. It’s just 14 lines. Ten syllables each (or 11, if you’re feeling Italian). Write to your love, to your cat, or just about how much you love poems.