Framing Devices in World War II Books

When I sat down to write this article, it was for my usual reason: something had annoyed me and I wanted to grouch about it to as many people as possible. And as also often happens, I sat down to start griping…and the gripe turned into a thought process, and it became all the more interesting than me going grouch grouch grouch grouch.

I was reading The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, an award-winning and much-discussed novel which had been recommended to me a dozen times over, at least. On the whole, it’s an excellent book with a compelling premise: It’s the story of a young girl in World War II Germany who has not only been abandoned by her mother and given to an elderly couple but must also deal with an increasingly war-torn country. She begins to steal and salvage books, desperate to read. That plot, all by itself, is compelling, and on the whole, it’s well-written and engaging…but the book has a gimmick, which is that the overall story is narrated by Death.

Death, personified, is speaking to us in the book and is first musing on war and killing and his difficult job, and gradually this leads to him recalling the life of the Book Thief and the few times that he encountered her.

It irritated the crap out of me; I found it not only unnecessary, but even worse, it had a distancing effect on the story, which was otherwise well-written enough to be immersive, and I think this is what I objected to most. My line of thought was, when dealing with something as brutal and earth-shattering as being a child during the Second World War, why do we need to blunt the razor-sharp edge of the topic? It was almost – I thought – an act of narrative cowardice.

So that’s what I came here to complain about, that distancing mechanism. But…then I thought about it a little longer, and I began to look at my own bookshelves, which is what I do in any situation. And as I looked, I realized something kind of interesting:

I was reading The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, an award-winning and much-discussed novel which had been recommended to me a dozen times over, at least. On the whole, it’s an excellent book with a compelling premise: It’s the story of a young girl in World War II Germany who has not only been abandoned by her mother and given to an elderly couple but must also deal with an increasingly war-torn country. She begins to steal and salvage books, desperate to read. That plot, all by itself, is compelling, and on the whole, it’s well-written and engaging…but the book has a gimmick, which is that the overall story is narrated by Death.

Death, personified, is speaking to us in the book and is first musing on war and killing and his difficult job, and gradually this leads to him recalling the life of the Book Thief and the few times that he encountered her.

It irritated the crap out of me; I found it not only unnecessary, but even worse, it had a distancing effect on the story, which was otherwise well-written enough to be immersive, and I think this is what I objected to most. My line of thought was, when dealing with something as brutal and earth-shattering as being a child during the Second World War, why do we need to blunt the razor-sharp edge of the topic? It was almost – I thought – an act of narrative cowardice.

So that’s what I came here to complain about, that distancing mechanism. But…then I thought about it a little longer, and I began to look at my own bookshelves, which is what I do in any situation. And as I looked, I realized something kind of interesting:

Maus by Art Spiegelman is not only a classic piece of comic history, it’s also – to my mind – one of the most powerful and interesting works of Holocaust literature ever written. It’s the story of Art Spiegelman’s own father and his youthful experiences in World War II and in the concentration camps. As with any work of art about the Holocaust, it’s heartbreaking and powerful and frequently difficult to read.

But Maus also employs some interesting framing and distancing devices of its own. For one thing, the whole work is told in a very simple, cartooning style. It takes the classic conceit of making all the characters animals and runs with it: the Jews are mice (maus, in German), the Germans are cats, the Polish, when they appear, are pigs. Furthermore, the story is being told throughout the comic, by Art Spiegelman’s father, to his son, who draws it. You not only get the WWII narrative, you get an exploration of their life now…and in volume 2, you get all of that, plus Art Spiegelman dealing with the publication of volume 1 and what that means.

Maus by Art Spiegelman is not only a classic piece of comic history, it’s also – to my mind – one of the most powerful and interesting works of Holocaust literature ever written. It’s the story of Art Spiegelman’s own father and his youthful experiences in World War II and in the concentration camps. As with any work of art about the Holocaust, it’s heartbreaking and powerful and frequently difficult to read.

But Maus also employs some interesting framing and distancing devices of its own. For one thing, the whole work is told in a very simple, cartooning style. It takes the classic conceit of making all the characters animals and runs with it: the Jews are mice (maus, in German), the Germans are cats, the Polish, when they appear, are pigs. Furthermore, the story is being told throughout the comic, by Art Spiegelman’s father, to his son, who draws it. You not only get the WWII narrative, you get an exploration of their life now…and in volume 2, you get all of that, plus Art Spiegelman dealing with the publication of volume 1 and what that means.

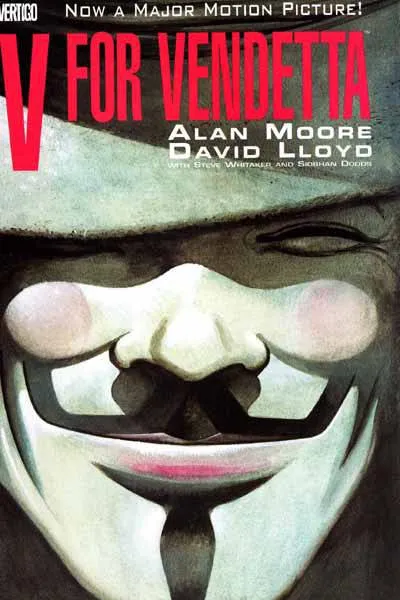

There’s V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, another comic book, a look at a fascist dictatorship which has taken over Britain in the unreachable far future of the year 1997. Standing against this totalitarian Nazi-like order is V, resplendent in his cloak and Guy Fawkes mask (not yet being used to Occupy anything). It’s a complex examination of living in a fascist police state: not all of the fascists are actually evil, and those who are aren’t cartoon Nazis. Likewise, V may be the titular hero of the book, but he isn’t pure, heroic, or occasionally anything less than sociopathic, in either his ideals or his actions.

It’s a meditation on power and anarchy and fascism and the choices individuals make not to be good or evil, but to just stay alive…and it is very much about World War II and Nazi Germany and the Holocaust (in that many ‘undesirable’ elements have been purged from this England) and again we see distancing devices in the narrative. Not only is it a comic, and an adventure story which allows it to touch on these issues without putting tremendous weight on the reader through them, but it also transfers the action to a slightly futuristic setting, and puts it in England.

There are plenty of other works similarly constructed which I’ve not mentioned. In fact, I discovered that the only World War II/Holocaust book on my shelf which doesn’t have a distancing method in place somehow is Elie Wiesel’s heart-wrenching and powerful book Night. My theory there is that having lived it directly, he doesn’t need the distancing device.

The end of my train of thought comes back to The Book Thief, then. I no longer think the distancing method of using Death himself as a narrator is actually an act of cowardice and being unwilling to confront such a brutal topic, but that it’s vitally necessary in order to approach these topics and deal with them in anything over than the most grueling and brutal terms (even with a way to be slightly removed, they’re still pretty rough. Maus has moments of old-man-grouching that are funny as hell, but even with the humor, they are rough stories to get through).

It all ends okay, too, in that eventually the distancing technique calms down in The Book Thief and the narrative itself swells to fill your attention. In the end, its an excellent, powerful book and I enjoyed it enormously. And I’m grateful that it gave me this issue to think about.

Always examine the things that make you grouchy, that’s another lesson we take from all this.

____________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.

There’s V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, another comic book, a look at a fascist dictatorship which has taken over Britain in the unreachable far future of the year 1997. Standing against this totalitarian Nazi-like order is V, resplendent in his cloak and Guy Fawkes mask (not yet being used to Occupy anything). It’s a complex examination of living in a fascist police state: not all of the fascists are actually evil, and those who are aren’t cartoon Nazis. Likewise, V may be the titular hero of the book, but he isn’t pure, heroic, or occasionally anything less than sociopathic, in either his ideals or his actions.

It’s a meditation on power and anarchy and fascism and the choices individuals make not to be good or evil, but to just stay alive…and it is very much about World War II and Nazi Germany and the Holocaust (in that many ‘undesirable’ elements have been purged from this England) and again we see distancing devices in the narrative. Not only is it a comic, and an adventure story which allows it to touch on these issues without putting tremendous weight on the reader through them, but it also transfers the action to a slightly futuristic setting, and puts it in England.

There are plenty of other works similarly constructed which I’ve not mentioned. In fact, I discovered that the only World War II/Holocaust book on my shelf which doesn’t have a distancing method in place somehow is Elie Wiesel’s heart-wrenching and powerful book Night. My theory there is that having lived it directly, he doesn’t need the distancing device.

The end of my train of thought comes back to The Book Thief, then. I no longer think the distancing method of using Death himself as a narrator is actually an act of cowardice and being unwilling to confront such a brutal topic, but that it’s vitally necessary in order to approach these topics and deal with them in anything over than the most grueling and brutal terms (even with a way to be slightly removed, they’re still pretty rough. Maus has moments of old-man-grouching that are funny as hell, but even with the humor, they are rough stories to get through).

It all ends okay, too, in that eventually the distancing technique calms down in The Book Thief and the narrative itself swells to fill your attention. In the end, its an excellent, powerful book and I enjoyed it enormously. And I’m grateful that it gave me this issue to think about.

Always examine the things that make you grouchy, that’s another lesson we take from all this.

____________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.

I was reading The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, an award-winning and much-discussed novel which had been recommended to me a dozen times over, at least. On the whole, it’s an excellent book with a compelling premise: It’s the story of a young girl in World War II Germany who has not only been abandoned by her mother and given to an elderly couple but must also deal with an increasingly war-torn country. She begins to steal and salvage books, desperate to read. That plot, all by itself, is compelling, and on the whole, it’s well-written and engaging…but the book has a gimmick, which is that the overall story is narrated by Death.

Death, personified, is speaking to us in the book and is first musing on war and killing and his difficult job, and gradually this leads to him recalling the life of the Book Thief and the few times that he encountered her.

It irritated the crap out of me; I found it not only unnecessary, but even worse, it had a distancing effect on the story, which was otherwise well-written enough to be immersive, and I think this is what I objected to most. My line of thought was, when dealing with something as brutal and earth-shattering as being a child during the Second World War, why do we need to blunt the razor-sharp edge of the topic? It was almost – I thought – an act of narrative cowardice.

So that’s what I came here to complain about, that distancing mechanism. But…then I thought about it a little longer, and I began to look at my own bookshelves, which is what I do in any situation. And as I looked, I realized something kind of interesting:

I was reading The Book Thief by Markus Zusak, an award-winning and much-discussed novel which had been recommended to me a dozen times over, at least. On the whole, it’s an excellent book with a compelling premise: It’s the story of a young girl in World War II Germany who has not only been abandoned by her mother and given to an elderly couple but must also deal with an increasingly war-torn country. She begins to steal and salvage books, desperate to read. That plot, all by itself, is compelling, and on the whole, it’s well-written and engaging…but the book has a gimmick, which is that the overall story is narrated by Death.

Death, personified, is speaking to us in the book and is first musing on war and killing and his difficult job, and gradually this leads to him recalling the life of the Book Thief and the few times that he encountered her.

It irritated the crap out of me; I found it not only unnecessary, but even worse, it had a distancing effect on the story, which was otherwise well-written enough to be immersive, and I think this is what I objected to most. My line of thought was, when dealing with something as brutal and earth-shattering as being a child during the Second World War, why do we need to blunt the razor-sharp edge of the topic? It was almost – I thought – an act of narrative cowardice.

So that’s what I came here to complain about, that distancing mechanism. But…then I thought about it a little longer, and I began to look at my own bookshelves, which is what I do in any situation. And as I looked, I realized something kind of interesting:

Maus by Art Spiegelman is not only a classic piece of comic history, it’s also – to my mind – one of the most powerful and interesting works of Holocaust literature ever written. It’s the story of Art Spiegelman’s own father and his youthful experiences in World War II and in the concentration camps. As with any work of art about the Holocaust, it’s heartbreaking and powerful and frequently difficult to read.

But Maus also employs some interesting framing and distancing devices of its own. For one thing, the whole work is told in a very simple, cartooning style. It takes the classic conceit of making all the characters animals and runs with it: the Jews are mice (maus, in German), the Germans are cats, the Polish, when they appear, are pigs. Furthermore, the story is being told throughout the comic, by Art Spiegelman’s father, to his son, who draws it. You not only get the WWII narrative, you get an exploration of their life now…and in volume 2, you get all of that, plus Art Spiegelman dealing with the publication of volume 1 and what that means.

Maus by Art Spiegelman is not only a classic piece of comic history, it’s also – to my mind – one of the most powerful and interesting works of Holocaust literature ever written. It’s the story of Art Spiegelman’s own father and his youthful experiences in World War II and in the concentration camps. As with any work of art about the Holocaust, it’s heartbreaking and powerful and frequently difficult to read.

But Maus also employs some interesting framing and distancing devices of its own. For one thing, the whole work is told in a very simple, cartooning style. It takes the classic conceit of making all the characters animals and runs with it: the Jews are mice (maus, in German), the Germans are cats, the Polish, when they appear, are pigs. Furthermore, the story is being told throughout the comic, by Art Spiegelman’s father, to his son, who draws it. You not only get the WWII narrative, you get an exploration of their life now…and in volume 2, you get all of that, plus Art Spiegelman dealing with the publication of volume 1 and what that means.

There’s V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, another comic book, a look at a fascist dictatorship which has taken over Britain in the unreachable far future of the year 1997. Standing against this totalitarian Nazi-like order is V, resplendent in his cloak and Guy Fawkes mask (not yet being used to Occupy anything). It’s a complex examination of living in a fascist police state: not all of the fascists are actually evil, and those who are aren’t cartoon Nazis. Likewise, V may be the titular hero of the book, but he isn’t pure, heroic, or occasionally anything less than sociopathic, in either his ideals or his actions.

It’s a meditation on power and anarchy and fascism and the choices individuals make not to be good or evil, but to just stay alive…and it is very much about World War II and Nazi Germany and the Holocaust (in that many ‘undesirable’ elements have been purged from this England) and again we see distancing devices in the narrative. Not only is it a comic, and an adventure story which allows it to touch on these issues without putting tremendous weight on the reader through them, but it also transfers the action to a slightly futuristic setting, and puts it in England.

There are plenty of other works similarly constructed which I’ve not mentioned. In fact, I discovered that the only World War II/Holocaust book on my shelf which doesn’t have a distancing method in place somehow is Elie Wiesel’s heart-wrenching and powerful book Night. My theory there is that having lived it directly, he doesn’t need the distancing device.

The end of my train of thought comes back to The Book Thief, then. I no longer think the distancing method of using Death himself as a narrator is actually an act of cowardice and being unwilling to confront such a brutal topic, but that it’s vitally necessary in order to approach these topics and deal with them in anything over than the most grueling and brutal terms (even with a way to be slightly removed, they’re still pretty rough. Maus has moments of old-man-grouching that are funny as hell, but even with the humor, they are rough stories to get through).

It all ends okay, too, in that eventually the distancing technique calms down in The Book Thief and the narrative itself swells to fill your attention. In the end, its an excellent, powerful book and I enjoyed it enormously. And I’m grateful that it gave me this issue to think about.

Always examine the things that make you grouchy, that’s another lesson we take from all this.

____________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.

There’s V for Vendetta by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, another comic book, a look at a fascist dictatorship which has taken over Britain in the unreachable far future of the year 1997. Standing against this totalitarian Nazi-like order is V, resplendent in his cloak and Guy Fawkes mask (not yet being used to Occupy anything). It’s a complex examination of living in a fascist police state: not all of the fascists are actually evil, and those who are aren’t cartoon Nazis. Likewise, V may be the titular hero of the book, but he isn’t pure, heroic, or occasionally anything less than sociopathic, in either his ideals or his actions.

It’s a meditation on power and anarchy and fascism and the choices individuals make not to be good or evil, but to just stay alive…and it is very much about World War II and Nazi Germany and the Holocaust (in that many ‘undesirable’ elements have been purged from this England) and again we see distancing devices in the narrative. Not only is it a comic, and an adventure story which allows it to touch on these issues without putting tremendous weight on the reader through them, but it also transfers the action to a slightly futuristic setting, and puts it in England.

There are plenty of other works similarly constructed which I’ve not mentioned. In fact, I discovered that the only World War II/Holocaust book on my shelf which doesn’t have a distancing method in place somehow is Elie Wiesel’s heart-wrenching and powerful book Night. My theory there is that having lived it directly, he doesn’t need the distancing device.

The end of my train of thought comes back to The Book Thief, then. I no longer think the distancing method of using Death himself as a narrator is actually an act of cowardice and being unwilling to confront such a brutal topic, but that it’s vitally necessary in order to approach these topics and deal with them in anything over than the most grueling and brutal terms (even with a way to be slightly removed, they’re still pretty rough. Maus has moments of old-man-grouching that are funny as hell, but even with the humor, they are rough stories to get through).

It all ends okay, too, in that eventually the distancing technique calms down in The Book Thief and the narrative itself swells to fill your attention. In the end, its an excellent, powerful book and I enjoyed it enormously. And I’m grateful that it gave me this issue to think about.

Always examine the things that make you grouchy, that’s another lesson we take from all this.

____________________________

Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every two weeks. No spam. We promise.

To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.