The Fading Pulp Magazine Subculture

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

My sixth-grade teacher, Mrs. Saunders, read us A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle the year it was first published. I didn’t know it then, but that story set me on a path towards pulp magazines. It was 1962, I was eleven. L’Engle’s story infected me with the science fiction bug by passing on memes that first emerged in Amazing Stories and Astounding Science Fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. As a sixth-grader, I did not know about genres, but I’d walk up and down the shelves at Air Base Elementary or the base library at Homestead Air Force Base looking for books about space travel.

By the eighth grade, I was a dedicated bookworm. I could now distinguish genres by cover art or the blurbs on dust jackets, but I was yet to know how genres emerged from the pulp magazine era. Fiction hasn’t always been pigeonholed into convenient categories allowing bookworms to binge-read their favorite kinds of stories.

About a year later I stumbled onto two old books in the dusty stacks of the Miami Public Library, worn down and rebound, that were early hardbacks of science fiction. One was Adventures in Time and Space (1946) edited by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas and the other was A Treasury of Science Fiction (1948) edited by Groff Conklin. These two pioneering works collected the best science fiction short stories from the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s. I was getting very close to the source of the river we call science fiction.

My sixth-grade teacher, Mrs. Saunders, read us A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle the year it was first published. I didn’t know it then, but that story set me on a path towards pulp magazines. It was 1962, I was eleven. L’Engle’s story infected me with the science fiction bug by passing on memes that first emerged in Amazing Stories and Astounding Science Fiction in the 1920s and 1930s. As a sixth-grader, I did not know about genres, but I’d walk up and down the shelves at Air Base Elementary or the base library at Homestead Air Force Base looking for books about space travel.

By the eighth grade, I was a dedicated bookworm. I could now distinguish genres by cover art or the blurbs on dust jackets, but I was yet to know how genres emerged from the pulp magazine era. Fiction hasn’t always been pigeonholed into convenient categories allowing bookworms to binge-read their favorite kinds of stories.

About a year later I stumbled onto two old books in the dusty stacks of the Miami Public Library, worn down and rebound, that were early hardbacks of science fiction. One was Adventures in Time and Space (1946) edited by Raymond J. Healy and J. Francis McComas and the other was A Treasury of Science Fiction (1948) edited by Groff Conklin. These two pioneering works collected the best science fiction short stories from the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s. I was getting very close to the source of the river we call science fiction.

Then I found science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz and his books, Explorers of the Infinite (1963) and Seekers of Tomorrow (1965), that gave the history of both science fiction and pulp magazines, roughly 1900–1950. By this time, I was in ninth grade, making my own money with a paper route and mowing lawns and starting to buy books. I found a used bookstore that sold old digest size magazines that were the descendants of pulp magazines, including Galaxy, If, Analog, Amazing, Fantastic, and F&SF. Only two of them still publish today.

Before Star Trek premiered in September 1966 I knew no one else who read science fiction. These magazines proved there were others like me, but where were they? At the time I thought I had discovered a secret subculture.

In the science fiction digests, I’d read essays by science fiction writers about when they were growing up reading the pulps and how they had to hide their copy of Astounding Science Fiction in respectable books because reading pulp fiction was considered very low class and reading science fiction meant you believed in that crazy Buck Rogers stuff. In 1967 I finally found a friend who read science fiction, and we’ve been arguing ever since because we didn’t agree which stories and authors were best.

I still didn’t know about the real pulp magazine then, but when I moved to Memphis in the early 1970s I saw a letter to the editor in Amazing Stories from a guy who lived in town. I found his name in the phone book and called him up. He told me about the local science fiction club. That’s where I met two older men who had large collections of pulp magazines. They were Darrell Richardson and Claude Saxon. The first club meeting I attended was at Richardson’s house, and he gave us a tour of his extensive collection. I learned later he had one of the largest collection of pulps in America—and he was a Baptist preacher. I became friends with Saxon, who had a large, but not famous, collection. Claude inspired me to start buying old pulps and to get into silent movies. That’s the thing about the pulp fans, they also loved all kinds of old pop culture.

It was the early 1970s and I found fandom, fanzines, and conventions. I remember going to my first convention in Kansas City and thinking I had finally found my people. There were many buyers and sellers of pulps at the con. This is how I learn about older generations growing up reading the pulp magazines. Claude was a generation older than most of us in the science fiction club. His favorite pulp magazines were from the 1900s through the 1920s like All-Story, Argosy, Adventure, Blue Book, before the pulps broke into genre magazines.

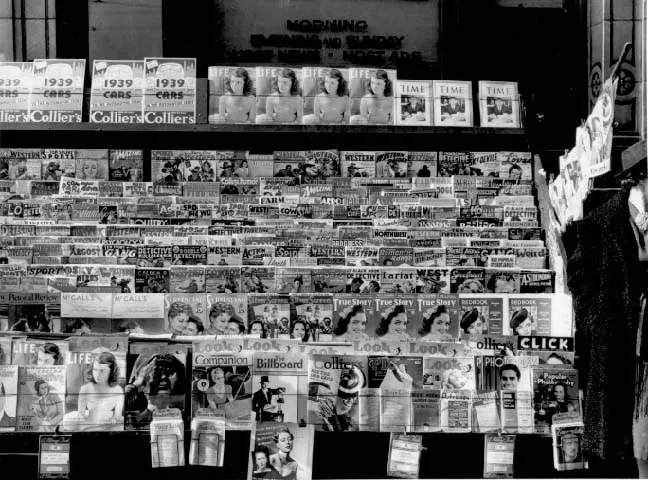

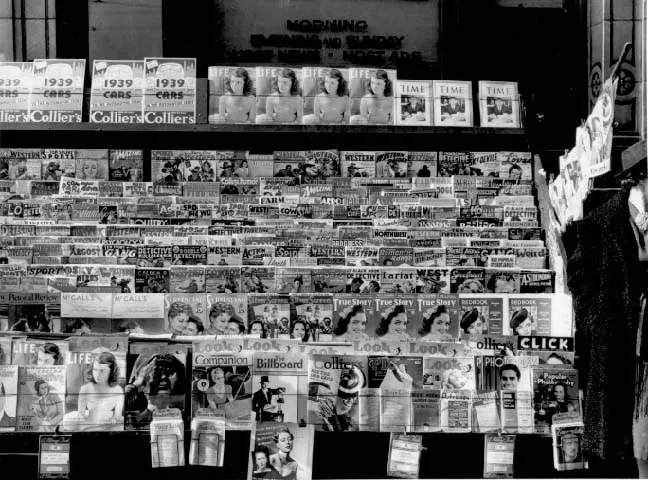

We owe or can blame the pulp magazine publishers for dividing fiction into marketing categories. Pulp magazines were television before television, providing Americans with fictional escapism. Short stories were like half-hour TV shows, novelettes were like hour shows, and novellas and serialized novels were like mini-series. Before television became popular in the 1950s, pulp magazine were the main source of popular fiction. The pulps offered way more genres than television ever did. In the 1950s the book, television, and movie industries consolidated the genres into westerns, mysteries, thrillers, fantasy, science fiction, horror, romance, and a few others; before that, fans could subscribe to dedicate magazines devoted to single topic stories like airplane combat or spicy ranch romances.

If I had born earlier, I might not have spent a lifetime of reading mostly science fiction. Claude read all kinds of pulp magazines. He loved detective pulps, western pulps, railroad pulps, aviation pulps, and so on. Claude seemed much older than his actual years, living in the past that existed before he was born. He was a big guy and reminded me of Sidney Greenstreet. He read more books than any other person than I’ve ever met, then and since. He handed down a love of pulp magazines to countless folks.

Then in 1977, I had to grow up. I stopped going to the science fiction club, quit going to conventions, and sold my science fiction books and pulp magazine collection. I got married and started a job I stuck with for 36 years. Now that I’m retired I’ve returned to reading pulps. I’ve bought a few pulps again but decided they are too old, too expensive, and too fragile to collect any more. But I have discovered a subculture on the internet that shares digital scans of the old pulp magazines. If you’re curious, try these sites:

Then I found science fiction historian Sam Moskowitz and his books, Explorers of the Infinite (1963) and Seekers of Tomorrow (1965), that gave the history of both science fiction and pulp magazines, roughly 1900–1950. By this time, I was in ninth grade, making my own money with a paper route and mowing lawns and starting to buy books. I found a used bookstore that sold old digest size magazines that were the descendants of pulp magazines, including Galaxy, If, Analog, Amazing, Fantastic, and F&SF. Only two of them still publish today.

Before Star Trek premiered in September 1966 I knew no one else who read science fiction. These magazines proved there were others like me, but where were they? At the time I thought I had discovered a secret subculture.

In the science fiction digests, I’d read essays by science fiction writers about when they were growing up reading the pulps and how they had to hide their copy of Astounding Science Fiction in respectable books because reading pulp fiction was considered very low class and reading science fiction meant you believed in that crazy Buck Rogers stuff. In 1967 I finally found a friend who read science fiction, and we’ve been arguing ever since because we didn’t agree which stories and authors were best.

I still didn’t know about the real pulp magazine then, but when I moved to Memphis in the early 1970s I saw a letter to the editor in Amazing Stories from a guy who lived in town. I found his name in the phone book and called him up. He told me about the local science fiction club. That’s where I met two older men who had large collections of pulp magazines. They were Darrell Richardson and Claude Saxon. The first club meeting I attended was at Richardson’s house, and he gave us a tour of his extensive collection. I learned later he had one of the largest collection of pulps in America—and he was a Baptist preacher. I became friends with Saxon, who had a large, but not famous, collection. Claude inspired me to start buying old pulps and to get into silent movies. That’s the thing about the pulp fans, they also loved all kinds of old pop culture.

It was the early 1970s and I found fandom, fanzines, and conventions. I remember going to my first convention in Kansas City and thinking I had finally found my people. There were many buyers and sellers of pulps at the con. This is how I learn about older generations growing up reading the pulp magazines. Claude was a generation older than most of us in the science fiction club. His favorite pulp magazines were from the 1900s through the 1920s like All-Story, Argosy, Adventure, Blue Book, before the pulps broke into genre magazines.

We owe or can blame the pulp magazine publishers for dividing fiction into marketing categories. Pulp magazines were television before television, providing Americans with fictional escapism. Short stories were like half-hour TV shows, novelettes were like hour shows, and novellas and serialized novels were like mini-series. Before television became popular in the 1950s, pulp magazine were the main source of popular fiction. The pulps offered way more genres than television ever did. In the 1950s the book, television, and movie industries consolidated the genres into westerns, mysteries, thrillers, fantasy, science fiction, horror, romance, and a few others; before that, fans could subscribe to dedicate magazines devoted to single topic stories like airplane combat or spicy ranch romances.

If I had born earlier, I might not have spent a lifetime of reading mostly science fiction. Claude read all kinds of pulp magazines. He loved detective pulps, western pulps, railroad pulps, aviation pulps, and so on. Claude seemed much older than his actual years, living in the past that existed before he was born. He was a big guy and reminded me of Sidney Greenstreet. He read more books than any other person than I’ve ever met, then and since. He handed down a love of pulp magazines to countless folks.

Then in 1977, I had to grow up. I stopped going to the science fiction club, quit going to conventions, and sold my science fiction books and pulp magazine collection. I got married and started a job I stuck with for 36 years. Now that I’m retired I’ve returned to reading pulps. I’ve bought a few pulps again but decided they are too old, too expensive, and too fragile to collect any more. But I have discovered a subculture on the internet that shares digital scans of the old pulp magazines. If you’re curious, try these sites:

Over the years, beautiful coffee table books about the pulps appear, but quickly go out-of-print. The Art of the Pulps: An Illustrated History is the most recent history.

Even back in the early 1970s, the pulp magazine subculture was dying. Television killed off pulp magazines in the 1950s, though a handful of digest-sized magazines continue to publish. At one time, hundreds of pulp titles filled the newsstands. Half-a-century later, a tiny subculture collects, cherishes, and preserves them. They still hold pulp magazine conventions, but the fans are old, and the cons are smaller. Old pulp fans lament they can’t get their kids and grandkids interested. They worry about what will happen to their collections.

Once again, the internet is changing things. Some old pulp fans are scanning their pulps and putting them online. It’s not legal, but no one cares. No one cares because so damn few people read the pulp magazines anymore, even when they are free. Yet, these pulp scanners are doing a kind of volunteer librarian work, creating special collections for researchers and possibly future readers. At first, pulp scanners quickly scanned issues and uploaded them. Then a few scanners started taking more pride in their work. They bought better scanners, they learned Photoshop, they started removing stains, rust marks, fixing smudges, tears, staple holes, creases, and even whiting the acid browned paper. I recently saw a scan of an old 1927 Saturday Evening Post that looked pristine with bright new pages.

Pulp magazines were printed on cheap wood pulp paper that’s not archival or acid-free. Their pages turn darker brown every year, becoming brittle. If you try to bend a corner to bookmark a page, the corner will snap off. It’s almost impossible to safely read a pulp magazine today without harming it. The pulp scanners use CBR/CBZ comic book file formats or the universal PDF formats that will preserve pulps as long as we keep our digital civilization going.

Pulp scanning is a labor of love. Mostly old bookworms are preserving the pop culture of their youth. Will lovers of today’s fan fiction work as hard to preserve their pop culture when they get to their social security years? Will fans of Harry Potter and Hermione Granger preserve all the extensive pop culture artifacts they generate when they reach Dumbledore’s age?

Now that I’m retired I’ve returned to reading old pulp magazines. I am among the few of the baby boomer generation that still loves the pulps. I got that love from an older generation. I’d like to see younger generations take up that love, but I doubt it will happen. I remember being in my twenties and meeting very old men, and they were always men, who remembered and collected dime novels. In the 1960s, Sam Moskowitz wrote about the dying generation of dime novel collectors, like I’m writing about the dying pulp fans now.

Most people embrace the pop culture of their formative years. A small percentage of every generation try to keep up with succeeding waves of newer pop culture. And a small percentage of us work backward in time embracing older generations of pop culture. I was born in 1951 and I have moved both forward and backward in time. I’ve stretched my pop culture embrace from the 1920s through the 1980s, and know a bit of the pop culture three decades on either end of that range.

The pulp magazine subculture is fading away. Its fans are dying, and I tend to feel genre distinctions are beginning to fade too. Writers now must top each other by writing multi-genre novels. Maybe it’s time to stop segregating fiction by theme. But then, if bookworms keep reading by genre they’re at least carrying on a tradition that started with the pulp magazines.