Women Have Always Loved Reading Thrillers—Just Ask the Victorians

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Thrillers are having a moment. Twisty, suspenseful stories about mistaken identities, missing girls, unreliable narrators, and domestic bliss that isn’t what it seems are all over the bestseller charts. You know the books I mean: everything from The Girl on the Train to Ruth Ware’s latest, The Turn of the Key. This style of crime fiction is often called a domestic thriller, which can best be described as a “psychological thriller that focuses on interpersonal relationships,” often those between husbands and wives or parents and children.

The domestic thriller has a particular focus on and association with women (perhaps that’s why the publishing industry seems to have saddled an entire sub-genre with such an eyeroll-inducing name). Many bestselling thriller authors are women. Many of the narrators of these novels are women, too. And many of the problems in these novels are those which concern women in particular: domestic violence and other forms of violence against women, including abduction and rape; husbands who aren’t who they claim to be; troublesome neighbours; gaslighting and emotional abuse; the demands of motherhood.

Thrillers are having a moment. Twisty, suspenseful stories about mistaken identities, missing girls, unreliable narrators, and domestic bliss that isn’t what it seems are all over the bestseller charts. You know the books I mean: everything from The Girl on the Train to Ruth Ware’s latest, The Turn of the Key. This style of crime fiction is often called a domestic thriller, which can best be described as a “psychological thriller that focuses on interpersonal relationships,” often those between husbands and wives or parents and children.

The domestic thriller has a particular focus on and association with women (perhaps that’s why the publishing industry seems to have saddled an entire sub-genre with such an eyeroll-inducing name). Many bestselling thriller authors are women. Many of the narrators of these novels are women, too. And many of the problems in these novels are those which concern women in particular: domestic violence and other forms of violence against women, including abduction and rape; husbands who aren’t who they claim to be; troublesome neighbours; gaslighting and emotional abuse; the demands of motherhood.

At CrimeReads, thriller writer Jessica Barry (author of Freefall) explores the ties women have to this genre, arguing that for women, thrillers can be heroic narratives. “The narrative is not—or at least not only, and not always—that bad things happen to women,” she writes. “It’s that women have the ability to survive when bad things happen.” And at Bustle, Mary Widdicks calls thrillers “a safe space” where women can encounter their fears in a controlled environment. Both are compelling arguments. If one half of the population regularly experiences violence and abuse, it only makes sense that that group of people would be drawn to stories where characters overcome similar behaviour or are offered some form of justice.

The thing is, women’s love for domestic thrillers isn’t anything new. Erin Kelly points out that marriage-gone-bad narratives, a staple of the genre, are as old as the Ancient Greeks and Shakespeare. And the domestic thriller as we know it today was born in the 19th century, with the rise of sensation fiction.

Sensation fiction was a popular genre of fiction that peaked in the 1860s. It was a fusion of genres including Gothic fiction, romance, and realist fiction; that fusion was a significant reason for its widespread popularity. Sensation fiction blended the juiciest, most sensational romantic and Gothic plot lines—think secret babies, kidnapping, poisoned spouses, and adultery, like Victorian-era soap operas. These topics all sound fantastic, but when they appear in familiar domestic settings, like a cozy family parlour, they take on a newly thrilling, threatening quality.

Sensation novels were meant to provoke intense emotion in readers, and boy did Victorian readers love that blend of crime and everyday life. Realism was already a popular form of fiction at the time, as seen in Dickens’s novels inspired by his experiences growing up in a workhouse (Little Dorrit) and by a real-life court case that dragged on for years (Bleak House). Sensation novels took the most salacious newspaper headlines, those about divorces, crimes, and murder cases, and made them as familiar to middle-class readers—the people who had money to spend on books and libraries—as a family sitting down to tea. Both domestic thrillers and sensation fiction have that ripped-from-the-headlines quality that we pretend we don’t love.

At CrimeReads, thriller writer Jessica Barry (author of Freefall) explores the ties women have to this genre, arguing that for women, thrillers can be heroic narratives. “The narrative is not—or at least not only, and not always—that bad things happen to women,” she writes. “It’s that women have the ability to survive when bad things happen.” And at Bustle, Mary Widdicks calls thrillers “a safe space” where women can encounter their fears in a controlled environment. Both are compelling arguments. If one half of the population regularly experiences violence and abuse, it only makes sense that that group of people would be drawn to stories where characters overcome similar behaviour or are offered some form of justice.

The thing is, women’s love for domestic thrillers isn’t anything new. Erin Kelly points out that marriage-gone-bad narratives, a staple of the genre, are as old as the Ancient Greeks and Shakespeare. And the domestic thriller as we know it today was born in the 19th century, with the rise of sensation fiction.

Sensation fiction was a popular genre of fiction that peaked in the 1860s. It was a fusion of genres including Gothic fiction, romance, and realist fiction; that fusion was a significant reason for its widespread popularity. Sensation fiction blended the juiciest, most sensational romantic and Gothic plot lines—think secret babies, kidnapping, poisoned spouses, and adultery, like Victorian-era soap operas. These topics all sound fantastic, but when they appear in familiar domestic settings, like a cozy family parlour, they take on a newly thrilling, threatening quality.

Sensation novels were meant to provoke intense emotion in readers, and boy did Victorian readers love that blend of crime and everyday life. Realism was already a popular form of fiction at the time, as seen in Dickens’s novels inspired by his experiences growing up in a workhouse (Little Dorrit) and by a real-life court case that dragged on for years (Bleak House). Sensation novels took the most salacious newspaper headlines, those about divorces, crimes, and murder cases, and made them as familiar to middle-class readers—the people who had money to spend on books and libraries—as a family sitting down to tea. Both domestic thrillers and sensation fiction have that ripped-from-the-headlines quality that we pretend we don’t love.

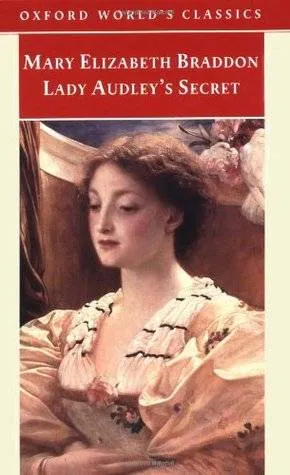

Wilkie Collins, author of The Moonstone, The Woman in White, and other books now considered to be classics, is probably the most well-known sensation fiction author. But, and this may not surprise you, it was a genre primarily associated with women. Authors such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon and Ellen Wood were hugely popular. Even the Brontës borrowed from sensation fiction. Braddon was known for Lady Audley’s Secret, a novel about, in the words of Matthew Sweet, “a murderously ambitious Pre-Raphaelite beauty who secures a fortune by shoving her husband down the garden well.” Published in 1862, it was one of the first sensation novels. Braddon’s books, and those by other sensation fiction authors, were very popular with female readers.

Serious Literary Critics, of course, were no fans of the sensation novel, and many worried that young women in particular would be corrupted by reading these tales of murder and mayhem. As you probably already know, Victorian society was strictly divided along gender lines, with men responsible for the public sphere and women confined to a private, domestic world. It’s no surprise that stories about women murdering their husbands, committing bigamy, having secret babies, and stealing jewels were looked upon with suspicion by critics and excitement by female readers. These novels threatened the very fabric of orderly middle-class Victorian life by allowing women to feel emotions and imagine situations far beyond their daily experiences.

Fast forward to 2019, and we have our own version of sensation fiction: the domestic thriller. Domestic thrillers aren’t quite as threatening to the fabric of our society. To me, they seem to reflect the worst bits of it back at us with a few distortions, like a funhouse mirror. Domestic thrillers can be an escape, but I think they’re also something of a punishment: look how bad we’ve let things get.

What domestic thrillers and sensation fiction both do so well is portray the crimes and betrayals experienced by women, from major violence to the everyday indignity of having a man belittle your opinion. Like female characters in Victorian sensation fiction, female protagonists in domestic thrillers may be unreliable; they may drink too much or withdraw from public life; they may have suspicions no one believes. They have a tragic incident in their pasts or a secret they can’t reveal. They definitely have a man in their life gaslighting them.

All of these are things that happen in real life. We think they’re just newspaper headlines, but they’re happening all around us behind closed doors. Domestic thrillers and sensation fiction—both shine light on a world that we think can’t touch us. It’s been there all along.

Wilkie Collins, author of The Moonstone, The Woman in White, and other books now considered to be classics, is probably the most well-known sensation fiction author. But, and this may not surprise you, it was a genre primarily associated with women. Authors such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon and Ellen Wood were hugely popular. Even the Brontës borrowed from sensation fiction. Braddon was known for Lady Audley’s Secret, a novel about, in the words of Matthew Sweet, “a murderously ambitious Pre-Raphaelite beauty who secures a fortune by shoving her husband down the garden well.” Published in 1862, it was one of the first sensation novels. Braddon’s books, and those by other sensation fiction authors, were very popular with female readers.

Serious Literary Critics, of course, were no fans of the sensation novel, and many worried that young women in particular would be corrupted by reading these tales of murder and mayhem. As you probably already know, Victorian society was strictly divided along gender lines, with men responsible for the public sphere and women confined to a private, domestic world. It’s no surprise that stories about women murdering their husbands, committing bigamy, having secret babies, and stealing jewels were looked upon with suspicion by critics and excitement by female readers. These novels threatened the very fabric of orderly middle-class Victorian life by allowing women to feel emotions and imagine situations far beyond their daily experiences.

Fast forward to 2019, and we have our own version of sensation fiction: the domestic thriller. Domestic thrillers aren’t quite as threatening to the fabric of our society. To me, they seem to reflect the worst bits of it back at us with a few distortions, like a funhouse mirror. Domestic thrillers can be an escape, but I think they’re also something of a punishment: look how bad we’ve let things get.

What domestic thrillers and sensation fiction both do so well is portray the crimes and betrayals experienced by women, from major violence to the everyday indignity of having a man belittle your opinion. Like female characters in Victorian sensation fiction, female protagonists in domestic thrillers may be unreliable; they may drink too much or withdraw from public life; they may have suspicions no one believes. They have a tragic incident in their pasts or a secret they can’t reveal. They definitely have a man in their life gaslighting them.

All of these are things that happen in real life. We think they’re just newspaper headlines, but they’re happening all around us behind closed doors. Domestic thrillers and sensation fiction—both shine light on a world that we think can’t touch us. It’s been there all along.