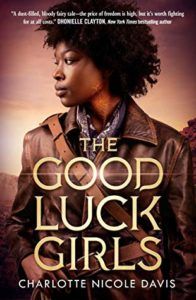

Balancing Real World Oppression with a Fantasy Western Romp

When Charlotte Nicole Davis set out to write The Good Luck Girls, she had two goals in mind. One was to write a fantasy story highlighting injustices of racism, sexism, and biases against queerness people face in our world. The other was to show readers with these identities that they belong in the adventure stories that have traditionally been assigned solely to white men. Many would view these aims as counter productive, but Davis felt getting both right was important.

The fantasy country of Arketta that Davis created helped her achieve these dual goals. It’s a world where a person’s shadow determines their social status. And desperate families sell their young daughters to “Welcome Houses” in hopes of a better life. These girls receive food and medical care they wouldn’t at home, but also receive brands that trap them in a life of prostitution they didn’t choose.

The story begins when, on her first night, Clementine accidentally kills a man who’s purchased her virginity—a “brag” as the characters in the book would call him. Her older sister, Aster, and three other girls decide escape the Welcome House with Clementine. Together, the five girls begin a journey to find their own freedom and get revenge on the men—and the systems—that hurt them.

The conceit of the shadow being the marker of race, which Davis said was inspired by vampires and demons, gives the author room to explore racial issues while still letting Black and Brown characters face adversity that has nothing to do with their skin color. Davis explained: “You have Black characters but they don’t face anti-blackness. Their race is based on whether or not you have a shadow. So it’s tackling those issues but still allowing readers to enjoy the fun of being on the run and being in a Western.”

Davis also wanted to show that there is intersectionality in the characters’ different levels of privilege. For example, there is a girl with a shadow, Violet, who works in the Welcome House with Aster and Clementine. “I think of her as my Malfoy character,” Davis said. “She has a sense of privilege and she clings to it. She’s hiding a deep sense of insecurity and feeling like she’s not good enough. She’s apologetically selfish in a way that’s very fun to write. I don’t think girls have to be likable and she was very fun to write.”

Davis obviously had fun but was very intentional when creating each girl in the group of runaways. Aster narrates the story, and her love for her little sister moves the plot forward. Davis described her conception, saying, “Aster is the angry black girl. And I really wanted it to be okay. I wanted one of the messages to be your anger is valid. And you don’t have to make yourself soft or sassy…You have a right to your anger, especially with the situation she’s in. And it can be useful if you know how to channel it into something useful. You can use your anger like a fuel.”

Davis created Clementine to show the opposite: that Black girls can also be soft, hopeful, and idealistic. She described Mallow as the most like herself and said, “A lot of the gender and queerness stuff, I projected that onto her.” And the fifth girl, Tansy, shows a medicine-obsessed girl with a concrete goal for her future. Davis also created Tansy to put her own twist on the nursing a patient back to life trope from classic Westerns. But I won’t say more about that to avoid spoilers.

Of the numerous tropes she put into the book, Davis explained: “There are certain things in Westerns that girls and especially girls of color don’t get to do in books. I really wanted us to be seen doing [them].” With the early murder, highway robberies, some light romance, and the many other adventures these Good Luck Girls face—as a reader, she certainly accomplished this. Although Davis added there are a few tropes she didn’t fit in that she hopes to add to the sequel.

Davis also wrote Zee, the one sympathetic male character, to correct the stereotypical view Westerns created about cowboys. Davis said, “In real life, being a cowboy was a poor man’s job. It was mostly immigrants and people of color. So the idea they were all these handsome white Hollywood John Wayne types is very historically inaccurate. It was mostly poor folks trying to make money. There’s a long history of Black and indigenous cowboys that we don’t get to see.”

Talking to Charlotte Nicole Davis, the high level of detailed thought she put into her debut novel was clear. The trigger warning in the front of the book. Balancing an inclusive cast of characters. Her lowkey obsession with using her library subscription to access the Oxford English Dictionary to get the characters’ slang right. These are just a few examples of her thoughtfulness while writing. And it shows in the complex story Davis created and the myriad of themes she weaved into The Good Luck Girls.