Anatomy of a Scene: Darcy’s (first) Proposal

While we at the Riot take some time off to rest and catch up on our reading, we’re re-running some of our favorite posts from the last several months. Enjoy our highlight reel, and we’ll be back with new stuff on Monday, July 11th.

This post originally ran February 16, 2016.

For this very special post-Valentine’s Day edition of Anatomy of a Scene, I am showing my love for you all by giving you a very special gift: a Pride and Prejudice piece that doesn’t begin with a cutesy “it is a truth universally acknowledged …” joke. Because yes, I think we can all safely agree that Pride and Prejudice has rightly earned its place as one of the most popular and acclaimed novels in the English literary canon and that it features one of the most widely-beloved romantic pairings. Jane Austen’s novel has inspired film, television, radio and theatre adaptations, clothing and accessories, a host of unofficial sequels and spin-offs, and of course fanfiction. We love us some Lizzie and Darcy. Generally speaking when I write this feature I try to walk a fine line when choosing a scene to study. The scene needs to be important enough to the story to make the cut in multiple adaptations but not so ubiquitous that I feel like it’s been done to death. When it comes to Elizabeth and Darcy, though, every scene feels iconic. That said and seeing as it’s Valentine’s Day, I’ll run the risk of being trite and talk about one of the most memorable moments in Austen’s novel: Darcy’s first proposal. After a series of prickly, charged, and occasionally awkward encounters, Darcy confesses his love for Elizabeth and proposes to her in this scene. Darcy (arrogantly, obliviously) declares that his feelings for Elizabeth exist against his will and, due to her inferior status, his better judgement, but that they cannot be helped. Elizabeth, understandably offended and still reeling from the knowledge that it was by Darcy’s hand that Jane and Bingley were separated and (she is led to believe) that Wickham has suffered a shocking disinheritance, refuses. The scene happens at approximately the halfway point of the novel and certainly its turning point. The adaptations of this scene I’ll be looking at are from: the 1995 miniseries adapted by Andrew Davies and directed by Simon Langton; Garinder Chadha’s 2004 Bollywood-influenced romcom modernization, Bride and Prejudice; and the 2005 Joe Wright film. First up: the now-classic Pride and Prejudice miniseries, first broadcast on the BBC in the fall of 1995. Clocking in at three hundred and twenty minutes, Davies and Langton’s adaptation can certainly boast being the most thorough adaptation of Austen’s novel. Little is truncates or sacrificed here and Davies has received tremendous phrase for maintaining as much of her plot and prose as possible and for brilliantly rendering the manners of Austen’s world on the screen. In this version, Elizabeth Bennett is played by Jennifer Ehle and Fitzwilliam Darcy is famously played by Colin Firth. Cards on the table: it’s hard to be objective about Colin Firth’s Darcy. For me and, I suspect, many women of my generation, he is Darcy. He’s the first Darcy we saw on screen and saturated late-’90s literary pop culture to such an extent that he was the Darcy some of us were already imagining when we first picked up Austen’s novel But imprinting aside, I believe there’s a reason Colin Firth is the Darcy of our hearts (and it’s not just his lush head of curls, strong chin, or his wet shirt). Firth gets it. He gets what makes Darcy tick and what makes his female audience tick: a throbbing heart trapped under layers of shyness, pretension, and social convention a meter thick. Up until this point Firth gives a relatively restrained performance but in this scene his Darcy literally cannot sit still. When he comes to call on Elizabeth at the Collins’ home, she sits down and invites him to follow suit. He does, for a moment, but he’s immediately up again. He literally cannot sit still: one minute he paces the room and the next turning to face Elizabeth, and then the next turning his back on her. Firth’s performance gives the impression of a man beside himself; a man overcome, undone, and nearly helpless. Ehle’s Elizabeth, by contrast, barely moves, the controlled flash of an eye or tilt of the chin conveying the range of emotions she is experiencing.

He literally cannot sit still: one minute he paces the room and the next turning to face Elizabeth, and then the next turning his back on her. Firth’s performance gives the impression of a man beside himself; a man overcome, undone, and nearly helpless. Ehle’s Elizabeth, by contrast, barely moves, the controlled flash of an eye or tilt of the chin conveying the range of emotions she is experiencing.

The actors’ performances, combined with Langton’s skilled blocking, suggest the power dynamics between Lizzie and Darcy. Throughout the scene, Elizabeth is seated while Darcy stands but rather than shoring up Darcy’s power, this contrast undermines it. Darcy may have the higher some interesting standing, but he is still the one literally out of control. Elizabeth can remain seated and still have command of the scene.

Firth’s delivery mirrors this indecisive, frenetic action. Several times he opens his mouth to speak before thinking the better of it. By the time he actually does work up the courage, he’s practically gasping. His line delivery, always clipped and abrupt, is hurried here, as if he is trying to push the words out of his mouth to get it all over with.

The actors’ performances, combined with Langton’s skilled blocking, suggest the power dynamics between Lizzie and Darcy. Throughout the scene, Elizabeth is seated while Darcy stands but rather than shoring up Darcy’s power, this contrast undermines it. Darcy may have the higher some interesting standing, but he is still the one literally out of control. Elizabeth can remain seated and still have command of the scene.

Firth’s delivery mirrors this indecisive, frenetic action. Several times he opens his mouth to speak before thinking the better of it. By the time he actually does work up the courage, he’s practically gasping. His line delivery, always clipped and abrupt, is hurried here, as if he is trying to push the words out of his mouth to get it all over with.

Most significantly, when he says the word “love” his voice breaks slightly and he drops it to a near-whisper. File this under “Firth gets it”: in this one word he conveys that Darcy is completely enamoured but also so totally embarrassed. It’s precisely this tension that makes Darcy simultaneously nearly-irresistable yet utterly unmarriageable. Sure, it’s romantic to have a man admit his feelings for you, but if he can’t say the world “love” without flinching, he isn’t for you (yet).

Langton visually demonstrates the distance and difference between Elizabeth and Darcy by shooting the two characters in contrasting backdrops within the same set. Throughout the scene Elizabeth is shot in front of a window partially obscured by a white, gauzy curtain and partially open to reveal a sun-drenched lawn.This backdrop suggests a wholesomeness and lack of pretension Langton reinforces throughout the series (see shots of Elizabeth frolicking with a dog or literally skipping through a field).

Most significantly, when he says the word “love” his voice breaks slightly and he drops it to a near-whisper. File this under “Firth gets it”: in this one word he conveys that Darcy is completely enamoured but also so totally embarrassed. It’s precisely this tension that makes Darcy simultaneously nearly-irresistable yet utterly unmarriageable. Sure, it’s romantic to have a man admit his feelings for you, but if he can’t say the world “love” without flinching, he isn’t for you (yet).

Langton visually demonstrates the distance and difference between Elizabeth and Darcy by shooting the two characters in contrasting backdrops within the same set. Throughout the scene Elizabeth is shot in front of a window partially obscured by a white, gauzy curtain and partially open to reveal a sun-drenched lawn.This backdrop suggests a wholesomeness and lack of pretension Langton reinforces throughout the series (see shots of Elizabeth frolicking with a dog or literally skipping through a field).

Darcy, by contrast, is shot against the living room wall with the fussy, suffocating brocade wallpaper almost overwhelming him. Where Elizabeth’s backdrop is evocative of a naturalness or even wildness, Darcy’s is an aesthetic representation of the weight of convention closing in on him.

Darcy, by contrast, is shot against the living room wall with the fussy, suffocating brocade wallpaper almost overwhelming him. Where Elizabeth’s backdrop is evocative of a naturalness or even wildness, Darcy’s is an aesthetic representation of the weight of convention closing in on him.

If we read this scene this way, it visually lays the groundwork for things to come. Surely it’s no coincidence that, later in the series, the moment Elizabeth begins to develop feelings for Darcy is the same moment as the infamous lake scene — Darcy’s own moment of wildness and communion with nature.

*****

Bride and Prejudice is Gurinder Chadha’s 2004 romcom modernization of Austen’s novel, a joyous genre-bender and culture-blender that mixes Austen’s novel with cheerful Bollywood-inspired musical sequences and surprisingly frank social commentary.

In Chadha’s film, Lizzie Bennett becomes Lalita Bakshi, a farmer’s daughter living with her sisters in the village of Amritsar and Fitzilliam Darcy comes William Darcy, an American hotelier who is visiting India with his friend, Balraj. Darcy is immediately taken with Lalita, but less so with India. In this true modernization of Austen’s story, Chadha insightfully recasts Darcy’s classism and snobbery as racist stereotyping and ignorance: he refers to the people of her village as Indian “hicks,” he implies that Indian women are “just more simple” than American women, and he is disdainful of arranged marriages. Lalita is understandably offended and dismisses him.

Darcy here is played by Martin Henderson and, with no offense intended to Mr. Henderson, his casting is the film’s biggest flaw. He’s aggressively fine: handsome in a square-jawed, even-featured Abercrombie sort of way way, but slightly bland and definitely no match for the incandescent Aishwarya Rai. Rai is an excellent modern Lizzie; she’s lively, imperious, and quick-witted, with a truly impressive glare that she deploys throughout this particular scene to great effect.

If we read this scene this way, it visually lays the groundwork for things to come. Surely it’s no coincidence that, later in the series, the moment Elizabeth begins to develop feelings for Darcy is the same moment as the infamous lake scene — Darcy’s own moment of wildness and communion with nature.

*****

Bride and Prejudice is Gurinder Chadha’s 2004 romcom modernization of Austen’s novel, a joyous genre-bender and culture-blender that mixes Austen’s novel with cheerful Bollywood-inspired musical sequences and surprisingly frank social commentary.

In Chadha’s film, Lizzie Bennett becomes Lalita Bakshi, a farmer’s daughter living with her sisters in the village of Amritsar and Fitzilliam Darcy comes William Darcy, an American hotelier who is visiting India with his friend, Balraj. Darcy is immediately taken with Lalita, but less so with India. In this true modernization of Austen’s story, Chadha insightfully recasts Darcy’s classism and snobbery as racist stereotyping and ignorance: he refers to the people of her village as Indian “hicks,” he implies that Indian women are “just more simple” than American women, and he is disdainful of arranged marriages. Lalita is understandably offended and dismisses him.

Darcy here is played by Martin Henderson and, with no offense intended to Mr. Henderson, his casting is the film’s biggest flaw. He’s aggressively fine: handsome in a square-jawed, even-featured Abercrombie sort of way way, but slightly bland and definitely no match for the incandescent Aishwarya Rai. Rai is an excellent modern Lizzie; she’s lively, imperious, and quick-witted, with a truly impressive glare that she deploys throughout this particular scene to great effect.

In this version of the scene — not a proposal but its modern narrative analogue, the first “I love you” — Lalita, her sisters and her mother have left India to attend the wedding of their relative, Mr. Kohli, and Lalita’s best friend, Chandra Lamba. The cross-cultural influence of the film are on full display in this scene of a heart-to-heart between an Indian woman and an American man during an Indian wedding on the grounds of an LA hotel landscaped to conjure an English garden.

In this version of the scene — not a proposal but its modern narrative analogue, the first “I love you” — Lalita, her sisters and her mother have left India to attend the wedding of their relative, Mr. Kohli, and Lalita’s best friend, Chandra Lamba. The cross-cultural influence of the film are on full display in this scene of a heart-to-heart between an Indian woman and an American man during an Indian wedding on the grounds of an LA hotel landscaped to conjure an English garden.

Chadha’s adaptation of this scene hits on all the important points from the novel: Darcy is in love with Lalita in spite of his better judgement and his mother’s wishes; Lalita is insulted on her own behalf and incensed on behalf of the wronged Wickham and especially her heartbroken sister, Jaya; Lalita declares that Darcy is the last person she could ever want. In fact, one of Chadha’s greatest feats of cinematic wizardry is the fact that her film manages to include all of Austen’s major plot points and multiple musical numbers in a running time of less than two hours.

While much of the meaning has been maintained, Austen’s prose itself has been appropriately modernized here. There is “no ardent admiration,” only love, and Darcy explicitly admits that he is jealous of Wickham rather than pettishly commenting on Elizabeth’s “interest in that gentleman’s affairs.” Most significantly, though, is that Lalita not only accuses Darcy of pride and arrogance, but also — in a callback to their first meeting when she sized him up as an American imperialist — of intolerance and insensitivity. This comment is particularly pointed because in this version, the audience has already seen the development of Darcy as a legitimate romantic interest and potential partner for Lalita and a basically good guy well-liked by his kid sister.

Chadha’s adaptation of this scene hits on all the important points from the novel: Darcy is in love with Lalita in spite of his better judgement and his mother’s wishes; Lalita is insulted on her own behalf and incensed on behalf of the wronged Wickham and especially her heartbroken sister, Jaya; Lalita declares that Darcy is the last person she could ever want. In fact, one of Chadha’s greatest feats of cinematic wizardry is the fact that her film manages to include all of Austen’s major plot points and multiple musical numbers in a running time of less than two hours.

While much of the meaning has been maintained, Austen’s prose itself has been appropriately modernized here. There is “no ardent admiration,” only love, and Darcy explicitly admits that he is jealous of Wickham rather than pettishly commenting on Elizabeth’s “interest in that gentleman’s affairs.” Most significantly, though, is that Lalita not only accuses Darcy of pride and arrogance, but also — in a callback to their first meeting when she sized him up as an American imperialist — of intolerance and insensitivity. This comment is particularly pointed because in this version, the audience has already seen the development of Darcy as a legitimate romantic interest and potential partner for Lalita and a basically good guy well-liked by his kid sister.

This leads me to another interesting aspect of this scene: where it falls in the larger story. In Austen’s novel, Darcy’s first proposal comes before he and Elizabeth begin to spend more time together. It happens before she sees Pemberley and hears how highly people speak of him and before she meets his sister.

But Chadha is incredibly adept at restructuring Austen’s marriage plot to fit the contours of the typical romcom plot. Generally speaking, the romcom develops along the following lines: a meet-cute, sometimes followed by a clash, and then a slow romantic build-up. Just when the relationship seems close to being realized (typically by a declaration of love), there is some kind of misunderstanding that drives the couple apart briefly before the final reunion.

This leads me to another interesting aspect of this scene: where it falls in the larger story. In Austen’s novel, Darcy’s first proposal comes before he and Elizabeth begin to spend more time together. It happens before she sees Pemberley and hears how highly people speak of him and before she meets his sister.

But Chadha is incredibly adept at restructuring Austen’s marriage plot to fit the contours of the typical romcom plot. Generally speaking, the romcom develops along the following lines: a meet-cute, sometimes followed by a clash, and then a slow romantic build-up. Just when the relationship seems close to being realized (typically by a declaration of love), there is some kind of misunderstanding that drives the couple apart briefly before the final reunion.

Chadha smartly pushes this scene forward and uses it, specifically Lalita’s discovery of Darcy’s role in parting Jaya and Balraj, as the Misunderstanding. It’s a clever narrative move and demonstrates her ability to truly adapt and update Austen and to make the classic novel her own.

*****

Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (coming only a year after Chadha’s) has been rightly lauded by film critics, but occupies a somewhat uneasy position in Austen scholarly and fan circles. It is often perceived as being not faithful enough or trying too hard to be modern, and it seems to exist under the shadow of the BBC miniseries of a decade earlier.

To my mind, what really distinguishes a good or at least interesting adaptation is simply having a take. There can only be so many scrupulously faithful adaptations of classic novels and if you’re adapting one that already has an incredibly faithful and incredibly popular adaptation in current memory, well, you might as well try an angle.

Wright’s film is not so much an adaptation of a novel but of a reading experience. His Pride and Prejudice, to my mind, captures the feeling of reading (and loving) Pride and Prejudice for the first time. The more you reread Austen, especially as an adult, the more you appreciate the sheer perfection of her novels: their intellectualism, wit, construction, prose, and precise development of characters. But I think younger, first-time readers — especially of the romantically-inclined variety — get swept away in the swoon of it all and this is the Pride and Prejudice that seems aimed squarely at them.

Deborah Moggach’s screenplay mixes some Austen’s prose with a great deal of original dialogue, which sometimes works and sometimes lands with a bit of a clang, as evidenced in this particular scene (“Well that’s because she’s shy!” is the kind of formulation it’s hard to buy as eighteenth-century speech).

Chadha smartly pushes this scene forward and uses it, specifically Lalita’s discovery of Darcy’s role in parting Jaya and Balraj, as the Misunderstanding. It’s a clever narrative move and demonstrates her ability to truly adapt and update Austen and to make the classic novel her own.

*****

Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (coming only a year after Chadha’s) has been rightly lauded by film critics, but occupies a somewhat uneasy position in Austen scholarly and fan circles. It is often perceived as being not faithful enough or trying too hard to be modern, and it seems to exist under the shadow of the BBC miniseries of a decade earlier.

To my mind, what really distinguishes a good or at least interesting adaptation is simply having a take. There can only be so many scrupulously faithful adaptations of classic novels and if you’re adapting one that already has an incredibly faithful and incredibly popular adaptation in current memory, well, you might as well try an angle.

Wright’s film is not so much an adaptation of a novel but of a reading experience. His Pride and Prejudice, to my mind, captures the feeling of reading (and loving) Pride and Prejudice for the first time. The more you reread Austen, especially as an adult, the more you appreciate the sheer perfection of her novels: their intellectualism, wit, construction, prose, and precise development of characters. But I think younger, first-time readers — especially of the romantically-inclined variety — get swept away in the swoon of it all and this is the Pride and Prejudice that seems aimed squarely at them.

Deborah Moggach’s screenplay mixes some Austen’s prose with a great deal of original dialogue, which sometimes works and sometimes lands with a bit of a clang, as evidenced in this particular scene (“Well that’s because she’s shy!” is the kind of formulation it’s hard to buy as eighteenth-century speech).

Visually, Wright’s Pride and Prejudice is like Jane Austen by way of the Brontë sisters, with gorgeous, saturated cinematography that’s all rolling, heathered hills, moody moors and rain-drenched stone. The tone of the film is simultaneously more sensual and more youthful than most Austen on screen.

The later is especially true of Keira Knightley’s Elizabeth. Elizabeth is, after all, not yet one-and-twenty, and there is a youthful impulsiveness to Knightley’s Lizzie that is quite different from Ehle’s centered, near-unflappable performance. Knightley’s line deliveries are more emotionally charged; often she blurts out some of Lizzie’s most famous quips and then looks slightly shocked at herself. It’s an insightful choice actually quite consistent with a character who is quick to make judgements.

Visually, Wright’s Pride and Prejudice is like Jane Austen by way of the Brontë sisters, with gorgeous, saturated cinematography that’s all rolling, heathered hills, moody moors and rain-drenched stone. The tone of the film is simultaneously more sensual and more youthful than most Austen on screen.

The later is especially true of Keira Knightley’s Elizabeth. Elizabeth is, after all, not yet one-and-twenty, and there is a youthful impulsiveness to Knightley’s Lizzie that is quite different from Ehle’s centered, near-unflappable performance. Knightley’s line deliveries are more emotionally charged; often she blurts out some of Lizzie’s most famous quips and then looks slightly shocked at herself. It’s an insightful choice actually quite consistent with a character who is quick to make judgements.

The proposal scene is a good example of this impetuousness; Elizabeth begins the scene coolly, but her emotions seem to escalate until, by the end, she is almost shouting at Darcy.

The proposal scene is a good example of this impetuousness; Elizabeth begins the scene coolly, but her emotions seem to escalate until, by the end, she is almost shouting at Darcy.

While the emotional weight of the BBC miniseries adaptation of this scene fell to Darcy, here it belongs to Elizabeth. Macfadyen’s yearning, hangdog expression changes only slightly from when he makes his original declaration to when he realizes his rejection; it gives the impression of a Darcy who approached this proposal with something less like a genuine hope and more like a need for an emotional exorcism.

While the emotional weight of the BBC miniseries adaptation of this scene fell to Darcy, here it belongs to Elizabeth. Macfadyen’s yearning, hangdog expression changes only slightly from when he makes his original declaration to when he realizes his rejection; it gives the impression of a Darcy who approached this proposal with something less like a genuine hope and more like a need for an emotional exorcism.

MacFadyen too delivers Darcy’s first few lines in rapid-fire succession. Even Knightley’s Elizabeth looks confused; it’s only until he blurts “I love you” that she really seems able to comprehend his meaning.

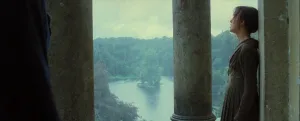

Wright pulls out all the stops to give the scene a distinctly sexual charge. He borrows a number of tropes from romance novels and films including the pouring rain that leaves his hero and heroine sopping wet and the the swelling music that opens the scene. Lizzie, overcome with exertion from fleeing a church, loosens her collar as she leans against a pillar.

MacFadyen too delivers Darcy’s first few lines in rapid-fire succession. Even Knightley’s Elizabeth looks confused; it’s only until he blurts “I love you” that she really seems able to comprehend his meaning.

Wright pulls out all the stops to give the scene a distinctly sexual charge. He borrows a number of tropes from romance novels and films including the pouring rain that leaves his hero and heroine sopping wet and the the swelling music that opens the scene. Lizzie, overcome with exertion from fleeing a church, loosens her collar as she leans against a pillar.

Wright even has Darcy accidentally startle Elizabeth, setting the stage for his speech with a jolt of adrenaline coursing through Elizabeth’s body. The majority of the conversation starts with the pair standing several feet apart. When Elizabeth mentions Wickham — Darcy’s romantic and, if we follow that line to its endpoint, sexual rival — that Darcy takes a step closer.

And then, of course, there is the controversial almost-kiss. After Elizabeth shoots out that he is “the last man I could ever be prevailed upon to marry,” this Darcy seems even more drawn to her, closing his eyes and inclining his mouth toward her. For her part, Elizabeth doesn’t flinch but actually leans into him before drawing back, again looking surprised at herself.

Wright even has Darcy accidentally startle Elizabeth, setting the stage for his speech with a jolt of adrenaline coursing through Elizabeth’s body. The majority of the conversation starts with the pair standing several feet apart. When Elizabeth mentions Wickham — Darcy’s romantic and, if we follow that line to its endpoint, sexual rival — that Darcy takes a step closer.

And then, of course, there is the controversial almost-kiss. After Elizabeth shoots out that he is “the last man I could ever be prevailed upon to marry,” this Darcy seems even more drawn to her, closing his eyes and inclining his mouth toward her. For her part, Elizabeth doesn’t flinch but actually leans into him before drawing back, again looking surprised at herself.

What Wright presents is a passionate physical attraction that has been underpinning Darcy and Elizabeth’s interactions since they first met, one that has come to a near-climax in this moment, the apex of his admiration and her indignation. Is this what Austen intended? Almost certainly not, but, on the other hand it’s not quite a fabrication (after all, Darcy does admire Elizabeth’s “fine eyes” and she later admits him “handsome”) as an acceleration and a case of making the subtext text.

*****

Even with only a decade between all three adaptations these feel like three very different interpretations of the scene, with different chronological, historical and physical settings and fairly different performances and tones. But all three, I think, hit on what makes this scene so perennially appealing: the combination of anticipation, disappointment, and promise. Some of the greatest pleasure is pleasure either anticipated or deferred and this scene offers both. Readers get the realized pleasure of the emotional declaration they have surely been anticipating since the moment Elizabeth and Darcy met combined with the thrill of knowing they’ll get to watch the romance continue to unfold because that proposal? They’ll have to wait for it.

What Wright presents is a passionate physical attraction that has been underpinning Darcy and Elizabeth’s interactions since they first met, one that has come to a near-climax in this moment, the apex of his admiration and her indignation. Is this what Austen intended? Almost certainly not, but, on the other hand it’s not quite a fabrication (after all, Darcy does admire Elizabeth’s “fine eyes” and she later admits him “handsome”) as an acceleration and a case of making the subtext text.

*****

Even with only a decade between all three adaptations these feel like three very different interpretations of the scene, with different chronological, historical and physical settings and fairly different performances and tones. But all three, I think, hit on what makes this scene so perennially appealing: the combination of anticipation, disappointment, and promise. Some of the greatest pleasure is pleasure either anticipated or deferred and this scene offers both. Readers get the realized pleasure of the emotional declaration they have surely been anticipating since the moment Elizabeth and Darcy met combined with the thrill of knowing they’ll get to watch the romance continue to unfold because that proposal? They’ll have to wait for it.

For this very special post-Valentine’s Day edition of Anatomy of a Scene, I am showing my love for you all by giving you a very special gift: a Pride and Prejudice piece that doesn’t begin with a cutesy “it is a truth universally acknowledged …” joke. Because yes, I think we can all safely agree that Pride and Prejudice has rightly earned its place as one of the most popular and acclaimed novels in the English literary canon and that it features one of the most widely-beloved romantic pairings. Jane Austen’s novel has inspired film, television, radio and theatre adaptations, clothing and accessories, a host of unofficial sequels and spin-offs, and of course fanfiction. We love us some Lizzie and Darcy. Generally speaking when I write this feature I try to walk a fine line when choosing a scene to study. The scene needs to be important enough to the story to make the cut in multiple adaptations but not so ubiquitous that I feel like it’s been done to death. When it comes to Elizabeth and Darcy, though, every scene feels iconic. That said and seeing as it’s Valentine’s Day, I’ll run the risk of being trite and talk about one of the most memorable moments in Austen’s novel: Darcy’s first proposal. After a series of prickly, charged, and occasionally awkward encounters, Darcy confesses his love for Elizabeth and proposes to her in this scene. Darcy (arrogantly, obliviously) declares that his feelings for Elizabeth exist against his will and, due to her inferior status, his better judgement, but that they cannot be helped. Elizabeth, understandably offended and still reeling from the knowledge that it was by Darcy’s hand that Jane and Bingley were separated and (she is led to believe) that Wickham has suffered a shocking disinheritance, refuses. The scene happens at approximately the halfway point of the novel and certainly its turning point. The adaptations of this scene I’ll be looking at are from: the 1995 miniseries adapted by Andrew Davies and directed by Simon Langton; Garinder Chadha’s 2004 Bollywood-influenced romcom modernization, Bride and Prejudice; and the 2005 Joe Wright film. First up: the now-classic Pride and Prejudice miniseries, first broadcast on the BBC in the fall of 1995. Clocking in at three hundred and twenty minutes, Davies and Langton’s adaptation can certainly boast being the most thorough adaptation of Austen’s novel. Little is truncates or sacrificed here and Davies has received tremendous phrase for maintaining as much of her plot and prose as possible and for brilliantly rendering the manners of Austen’s world on the screen. In this version, Elizabeth Bennett is played by Jennifer Ehle and Fitzwilliam Darcy is famously played by Colin Firth. Cards on the table: it’s hard to be objective about Colin Firth’s Darcy. For me and, I suspect, many women of my generation, he is Darcy. He’s the first Darcy we saw on screen and saturated late-’90s literary pop culture to such an extent that he was the Darcy some of us were already imagining when we first picked up Austen’s novel But imprinting aside, I believe there’s a reason Colin Firth is the Darcy of our hearts (and it’s not just his lush head of curls, strong chin, or his wet shirt). Firth gets it. He gets what makes Darcy tick and what makes his female audience tick: a throbbing heart trapped under layers of shyness, pretension, and social convention a meter thick. Up until this point Firth gives a relatively restrained performance but in this scene his Darcy literally cannot sit still. When he comes to call on Elizabeth at the Collins’ home, she sits down and invites him to follow suit. He does, for a moment, but he’s immediately up again.

He literally cannot sit still: one minute he paces the room and the next turning to face Elizabeth, and then the next turning his back on her. Firth’s performance gives the impression of a man beside himself; a man overcome, undone, and nearly helpless. Ehle’s Elizabeth, by contrast, barely moves, the controlled flash of an eye or tilt of the chin conveying the range of emotions she is experiencing.

He literally cannot sit still: one minute he paces the room and the next turning to face Elizabeth, and then the next turning his back on her. Firth’s performance gives the impression of a man beside himself; a man overcome, undone, and nearly helpless. Ehle’s Elizabeth, by contrast, barely moves, the controlled flash of an eye or tilt of the chin conveying the range of emotions she is experiencing.

The actors’ performances, combined with Langton’s skilled blocking, suggest the power dynamics between Lizzie and Darcy. Throughout the scene, Elizabeth is seated while Darcy stands but rather than shoring up Darcy’s power, this contrast undermines it. Darcy may have the higher some interesting standing, but he is still the one literally out of control. Elizabeth can remain seated and still have command of the scene.

Firth’s delivery mirrors this indecisive, frenetic action. Several times he opens his mouth to speak before thinking the better of it. By the time he actually does work up the courage, he’s practically gasping. His line delivery, always clipped and abrupt, is hurried here, as if he is trying to push the words out of his mouth to get it all over with.

The actors’ performances, combined with Langton’s skilled blocking, suggest the power dynamics between Lizzie and Darcy. Throughout the scene, Elizabeth is seated while Darcy stands but rather than shoring up Darcy’s power, this contrast undermines it. Darcy may have the higher some interesting standing, but he is still the one literally out of control. Elizabeth can remain seated and still have command of the scene.

Firth’s delivery mirrors this indecisive, frenetic action. Several times he opens his mouth to speak before thinking the better of it. By the time he actually does work up the courage, he’s practically gasping. His line delivery, always clipped and abrupt, is hurried here, as if he is trying to push the words out of his mouth to get it all over with.

Most significantly, when he says the word “love” his voice breaks slightly and he drops it to a near-whisper. File this under “Firth gets it”: in this one word he conveys that Darcy is completely enamoured but also so totally embarrassed. It’s precisely this tension that makes Darcy simultaneously nearly-irresistable yet utterly unmarriageable. Sure, it’s romantic to have a man admit his feelings for you, but if he can’t say the world “love” without flinching, he isn’t for you (yet).

Langton visually demonstrates the distance and difference between Elizabeth and Darcy by shooting the two characters in contrasting backdrops within the same set. Throughout the scene Elizabeth is shot in front of a window partially obscured by a white, gauzy curtain and partially open to reveal a sun-drenched lawn.This backdrop suggests a wholesomeness and lack of pretension Langton reinforces throughout the series (see shots of Elizabeth frolicking with a dog or literally skipping through a field).

Most significantly, when he says the word “love” his voice breaks slightly and he drops it to a near-whisper. File this under “Firth gets it”: in this one word he conveys that Darcy is completely enamoured but also so totally embarrassed. It’s precisely this tension that makes Darcy simultaneously nearly-irresistable yet utterly unmarriageable. Sure, it’s romantic to have a man admit his feelings for you, but if he can’t say the world “love” without flinching, he isn’t for you (yet).

Langton visually demonstrates the distance and difference between Elizabeth and Darcy by shooting the two characters in contrasting backdrops within the same set. Throughout the scene Elizabeth is shot in front of a window partially obscured by a white, gauzy curtain and partially open to reveal a sun-drenched lawn.This backdrop suggests a wholesomeness and lack of pretension Langton reinforces throughout the series (see shots of Elizabeth frolicking with a dog or literally skipping through a field).

Darcy, by contrast, is shot against the living room wall with the fussy, suffocating brocade wallpaper almost overwhelming him. Where Elizabeth’s backdrop is evocative of a naturalness or even wildness, Darcy’s is an aesthetic representation of the weight of convention closing in on him.

Darcy, by contrast, is shot against the living room wall with the fussy, suffocating brocade wallpaper almost overwhelming him. Where Elizabeth’s backdrop is evocative of a naturalness or even wildness, Darcy’s is an aesthetic representation of the weight of convention closing in on him.

If we read this scene this way, it visually lays the groundwork for things to come. Surely it’s no coincidence that, later in the series, the moment Elizabeth begins to develop feelings for Darcy is the same moment as the infamous lake scene — Darcy’s own moment of wildness and communion with nature.

*****

Bride and Prejudice is Gurinder Chadha’s 2004 romcom modernization of Austen’s novel, a joyous genre-bender and culture-blender that mixes Austen’s novel with cheerful Bollywood-inspired musical sequences and surprisingly frank social commentary.

In Chadha’s film, Lizzie Bennett becomes Lalita Bakshi, a farmer’s daughter living with her sisters in the village of Amritsar and Fitzilliam Darcy comes William Darcy, an American hotelier who is visiting India with his friend, Balraj. Darcy is immediately taken with Lalita, but less so with India. In this true modernization of Austen’s story, Chadha insightfully recasts Darcy’s classism and snobbery as racist stereotyping and ignorance: he refers to the people of her village as Indian “hicks,” he implies that Indian women are “just more simple” than American women, and he is disdainful of arranged marriages. Lalita is understandably offended and dismisses him.

Darcy here is played by Martin Henderson and, with no offense intended to Mr. Henderson, his casting is the film’s biggest flaw. He’s aggressively fine: handsome in a square-jawed, even-featured Abercrombie sort of way way, but slightly bland and definitely no match for the incandescent Aishwarya Rai. Rai is an excellent modern Lizzie; she’s lively, imperious, and quick-witted, with a truly impressive glare that she deploys throughout this particular scene to great effect.

If we read this scene this way, it visually lays the groundwork for things to come. Surely it’s no coincidence that, later in the series, the moment Elizabeth begins to develop feelings for Darcy is the same moment as the infamous lake scene — Darcy’s own moment of wildness and communion with nature.

*****

Bride and Prejudice is Gurinder Chadha’s 2004 romcom modernization of Austen’s novel, a joyous genre-bender and culture-blender that mixes Austen’s novel with cheerful Bollywood-inspired musical sequences and surprisingly frank social commentary.

In Chadha’s film, Lizzie Bennett becomes Lalita Bakshi, a farmer’s daughter living with her sisters in the village of Amritsar and Fitzilliam Darcy comes William Darcy, an American hotelier who is visiting India with his friend, Balraj. Darcy is immediately taken with Lalita, but less so with India. In this true modernization of Austen’s story, Chadha insightfully recasts Darcy’s classism and snobbery as racist stereotyping and ignorance: he refers to the people of her village as Indian “hicks,” he implies that Indian women are “just more simple” than American women, and he is disdainful of arranged marriages. Lalita is understandably offended and dismisses him.

Darcy here is played by Martin Henderson and, with no offense intended to Mr. Henderson, his casting is the film’s biggest flaw. He’s aggressively fine: handsome in a square-jawed, even-featured Abercrombie sort of way way, but slightly bland and definitely no match for the incandescent Aishwarya Rai. Rai is an excellent modern Lizzie; she’s lively, imperious, and quick-witted, with a truly impressive glare that she deploys throughout this particular scene to great effect.

In this version of the scene — not a proposal but its modern narrative analogue, the first “I love you” — Lalita, her sisters and her mother have left India to attend the wedding of their relative, Mr. Kohli, and Lalita’s best friend, Chandra Lamba. The cross-cultural influence of the film are on full display in this scene of a heart-to-heart between an Indian woman and an American man during an Indian wedding on the grounds of an LA hotel landscaped to conjure an English garden.

In this version of the scene — not a proposal but its modern narrative analogue, the first “I love you” — Lalita, her sisters and her mother have left India to attend the wedding of their relative, Mr. Kohli, and Lalita’s best friend, Chandra Lamba. The cross-cultural influence of the film are on full display in this scene of a heart-to-heart between an Indian woman and an American man during an Indian wedding on the grounds of an LA hotel landscaped to conjure an English garden.

Chadha’s adaptation of this scene hits on all the important points from the novel: Darcy is in love with Lalita in spite of his better judgement and his mother’s wishes; Lalita is insulted on her own behalf and incensed on behalf of the wronged Wickham and especially her heartbroken sister, Jaya; Lalita declares that Darcy is the last person she could ever want. In fact, one of Chadha’s greatest feats of cinematic wizardry is the fact that her film manages to include all of Austen’s major plot points and multiple musical numbers in a running time of less than two hours.

While much of the meaning has been maintained, Austen’s prose itself has been appropriately modernized here. There is “no ardent admiration,” only love, and Darcy explicitly admits that he is jealous of Wickham rather than pettishly commenting on Elizabeth’s “interest in that gentleman’s affairs.” Most significantly, though, is that Lalita not only accuses Darcy of pride and arrogance, but also — in a callback to their first meeting when she sized him up as an American imperialist — of intolerance and insensitivity. This comment is particularly pointed because in this version, the audience has already seen the development of Darcy as a legitimate romantic interest and potential partner for Lalita and a basically good guy well-liked by his kid sister.

Chadha’s adaptation of this scene hits on all the important points from the novel: Darcy is in love with Lalita in spite of his better judgement and his mother’s wishes; Lalita is insulted on her own behalf and incensed on behalf of the wronged Wickham and especially her heartbroken sister, Jaya; Lalita declares that Darcy is the last person she could ever want. In fact, one of Chadha’s greatest feats of cinematic wizardry is the fact that her film manages to include all of Austen’s major plot points and multiple musical numbers in a running time of less than two hours.

While much of the meaning has been maintained, Austen’s prose itself has been appropriately modernized here. There is “no ardent admiration,” only love, and Darcy explicitly admits that he is jealous of Wickham rather than pettishly commenting on Elizabeth’s “interest in that gentleman’s affairs.” Most significantly, though, is that Lalita not only accuses Darcy of pride and arrogance, but also — in a callback to their first meeting when she sized him up as an American imperialist — of intolerance and insensitivity. This comment is particularly pointed because in this version, the audience has already seen the development of Darcy as a legitimate romantic interest and potential partner for Lalita and a basically good guy well-liked by his kid sister.

This leads me to another interesting aspect of this scene: where it falls in the larger story. In Austen’s novel, Darcy’s first proposal comes before he and Elizabeth begin to spend more time together. It happens before she sees Pemberley and hears how highly people speak of him and before she meets his sister.

But Chadha is incredibly adept at restructuring Austen’s marriage plot to fit the contours of the typical romcom plot. Generally speaking, the romcom develops along the following lines: a meet-cute, sometimes followed by a clash, and then a slow romantic build-up. Just when the relationship seems close to being realized (typically by a declaration of love), there is some kind of misunderstanding that drives the couple apart briefly before the final reunion.

This leads me to another interesting aspect of this scene: where it falls in the larger story. In Austen’s novel, Darcy’s first proposal comes before he and Elizabeth begin to spend more time together. It happens before she sees Pemberley and hears how highly people speak of him and before she meets his sister.

But Chadha is incredibly adept at restructuring Austen’s marriage plot to fit the contours of the typical romcom plot. Generally speaking, the romcom develops along the following lines: a meet-cute, sometimes followed by a clash, and then a slow romantic build-up. Just when the relationship seems close to being realized (typically by a declaration of love), there is some kind of misunderstanding that drives the couple apart briefly before the final reunion.

Chadha smartly pushes this scene forward and uses it, specifically Lalita’s discovery of Darcy’s role in parting Jaya and Balraj, as the Misunderstanding. It’s a clever narrative move and demonstrates her ability to truly adapt and update Austen and to make the classic novel her own.

*****

Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (coming only a year after Chadha’s) has been rightly lauded by film critics, but occupies a somewhat uneasy position in Austen scholarly and fan circles. It is often perceived as being not faithful enough or trying too hard to be modern, and it seems to exist under the shadow of the BBC miniseries of a decade earlier.

To my mind, what really distinguishes a good or at least interesting adaptation is simply having a take. There can only be so many scrupulously faithful adaptations of classic novels and if you’re adapting one that already has an incredibly faithful and incredibly popular adaptation in current memory, well, you might as well try an angle.

Wright’s film is not so much an adaptation of a novel but of a reading experience. His Pride and Prejudice, to my mind, captures the feeling of reading (and loving) Pride and Prejudice for the first time. The more you reread Austen, especially as an adult, the more you appreciate the sheer perfection of her novels: their intellectualism, wit, construction, prose, and precise development of characters. But I think younger, first-time readers — especially of the romantically-inclined variety — get swept away in the swoon of it all and this is the Pride and Prejudice that seems aimed squarely at them.

Deborah Moggach’s screenplay mixes some Austen’s prose with a great deal of original dialogue, which sometimes works and sometimes lands with a bit of a clang, as evidenced in this particular scene (“Well that’s because she’s shy!” is the kind of formulation it’s hard to buy as eighteenth-century speech).

Chadha smartly pushes this scene forward and uses it, specifically Lalita’s discovery of Darcy’s role in parting Jaya and Balraj, as the Misunderstanding. It’s a clever narrative move and demonstrates her ability to truly adapt and update Austen and to make the classic novel her own.

*****

Joe Wright’s 2005 adaptation of Pride and Prejudice (coming only a year after Chadha’s) has been rightly lauded by film critics, but occupies a somewhat uneasy position in Austen scholarly and fan circles. It is often perceived as being not faithful enough or trying too hard to be modern, and it seems to exist under the shadow of the BBC miniseries of a decade earlier.

To my mind, what really distinguishes a good or at least interesting adaptation is simply having a take. There can only be so many scrupulously faithful adaptations of classic novels and if you’re adapting one that already has an incredibly faithful and incredibly popular adaptation in current memory, well, you might as well try an angle.

Wright’s film is not so much an adaptation of a novel but of a reading experience. His Pride and Prejudice, to my mind, captures the feeling of reading (and loving) Pride and Prejudice for the first time. The more you reread Austen, especially as an adult, the more you appreciate the sheer perfection of her novels: their intellectualism, wit, construction, prose, and precise development of characters. But I think younger, first-time readers — especially of the romantically-inclined variety — get swept away in the swoon of it all and this is the Pride and Prejudice that seems aimed squarely at them.

Deborah Moggach’s screenplay mixes some Austen’s prose with a great deal of original dialogue, which sometimes works and sometimes lands with a bit of a clang, as evidenced in this particular scene (“Well that’s because she’s shy!” is the kind of formulation it’s hard to buy as eighteenth-century speech).

Visually, Wright’s Pride and Prejudice is like Jane Austen by way of the Brontë sisters, with gorgeous, saturated cinematography that’s all rolling, heathered hills, moody moors and rain-drenched stone. The tone of the film is simultaneously more sensual and more youthful than most Austen on screen.

The later is especially true of Keira Knightley’s Elizabeth. Elizabeth is, after all, not yet one-and-twenty, and there is a youthful impulsiveness to Knightley’s Lizzie that is quite different from Ehle’s centered, near-unflappable performance. Knightley’s line deliveries are more emotionally charged; often she blurts out some of Lizzie’s most famous quips and then looks slightly shocked at herself. It’s an insightful choice actually quite consistent with a character who is quick to make judgements.

Visually, Wright’s Pride and Prejudice is like Jane Austen by way of the Brontë sisters, with gorgeous, saturated cinematography that’s all rolling, heathered hills, moody moors and rain-drenched stone. The tone of the film is simultaneously more sensual and more youthful than most Austen on screen.

The later is especially true of Keira Knightley’s Elizabeth. Elizabeth is, after all, not yet one-and-twenty, and there is a youthful impulsiveness to Knightley’s Lizzie that is quite different from Ehle’s centered, near-unflappable performance. Knightley’s line deliveries are more emotionally charged; often she blurts out some of Lizzie’s most famous quips and then looks slightly shocked at herself. It’s an insightful choice actually quite consistent with a character who is quick to make judgements.

The proposal scene is a good example of this impetuousness; Elizabeth begins the scene coolly, but her emotions seem to escalate until, by the end, she is almost shouting at Darcy.

The proposal scene is a good example of this impetuousness; Elizabeth begins the scene coolly, but her emotions seem to escalate until, by the end, she is almost shouting at Darcy.

While the emotional weight of the BBC miniseries adaptation of this scene fell to Darcy, here it belongs to Elizabeth. Macfadyen’s yearning, hangdog expression changes only slightly from when he makes his original declaration to when he realizes his rejection; it gives the impression of a Darcy who approached this proposal with something less like a genuine hope and more like a need for an emotional exorcism.

While the emotional weight of the BBC miniseries adaptation of this scene fell to Darcy, here it belongs to Elizabeth. Macfadyen’s yearning, hangdog expression changes only slightly from when he makes his original declaration to when he realizes his rejection; it gives the impression of a Darcy who approached this proposal with something less like a genuine hope and more like a need for an emotional exorcism.

MacFadyen too delivers Darcy’s first few lines in rapid-fire succession. Even Knightley’s Elizabeth looks confused; it’s only until he blurts “I love you” that she really seems able to comprehend his meaning.

Wright pulls out all the stops to give the scene a distinctly sexual charge. He borrows a number of tropes from romance novels and films including the pouring rain that leaves his hero and heroine sopping wet and the the swelling music that opens the scene. Lizzie, overcome with exertion from fleeing a church, loosens her collar as she leans against a pillar.

MacFadyen too delivers Darcy’s first few lines in rapid-fire succession. Even Knightley’s Elizabeth looks confused; it’s only until he blurts “I love you” that she really seems able to comprehend his meaning.

Wright pulls out all the stops to give the scene a distinctly sexual charge. He borrows a number of tropes from romance novels and films including the pouring rain that leaves his hero and heroine sopping wet and the the swelling music that opens the scene. Lizzie, overcome with exertion from fleeing a church, loosens her collar as she leans against a pillar.

Wright even has Darcy accidentally startle Elizabeth, setting the stage for his speech with a jolt of adrenaline coursing through Elizabeth’s body. The majority of the conversation starts with the pair standing several feet apart. When Elizabeth mentions Wickham — Darcy’s romantic and, if we follow that line to its endpoint, sexual rival — that Darcy takes a step closer.

And then, of course, there is the controversial almost-kiss. After Elizabeth shoots out that he is “the last man I could ever be prevailed upon to marry,” this Darcy seems even more drawn to her, closing his eyes and inclining his mouth toward her. For her part, Elizabeth doesn’t flinch but actually leans into him before drawing back, again looking surprised at herself.

Wright even has Darcy accidentally startle Elizabeth, setting the stage for his speech with a jolt of adrenaline coursing through Elizabeth’s body. The majority of the conversation starts with the pair standing several feet apart. When Elizabeth mentions Wickham — Darcy’s romantic and, if we follow that line to its endpoint, sexual rival — that Darcy takes a step closer.

And then, of course, there is the controversial almost-kiss. After Elizabeth shoots out that he is “the last man I could ever be prevailed upon to marry,” this Darcy seems even more drawn to her, closing his eyes and inclining his mouth toward her. For her part, Elizabeth doesn’t flinch but actually leans into him before drawing back, again looking surprised at herself.

What Wright presents is a passionate physical attraction that has been underpinning Darcy and Elizabeth’s interactions since they first met, one that has come to a near-climax in this moment, the apex of his admiration and her indignation. Is this what Austen intended? Almost certainly not, but, on the other hand it’s not quite a fabrication (after all, Darcy does admire Elizabeth’s “fine eyes” and she later admits him “handsome”) as an acceleration and a case of making the subtext text.

*****

Even with only a decade between all three adaptations these feel like three very different interpretations of the scene, with different chronological, historical and physical settings and fairly different performances and tones. But all three, I think, hit on what makes this scene so perennially appealing: the combination of anticipation, disappointment, and promise. Some of the greatest pleasure is pleasure either anticipated or deferred and this scene offers both. Readers get the realized pleasure of the emotional declaration they have surely been anticipating since the moment Elizabeth and Darcy met combined with the thrill of knowing they’ll get to watch the romance continue to unfold because that proposal? They’ll have to wait for it.

What Wright presents is a passionate physical attraction that has been underpinning Darcy and Elizabeth’s interactions since they first met, one that has come to a near-climax in this moment, the apex of his admiration and her indignation. Is this what Austen intended? Almost certainly not, but, on the other hand it’s not quite a fabrication (after all, Darcy does admire Elizabeth’s “fine eyes” and she later admits him “handsome”) as an acceleration and a case of making the subtext text.

*****

Even with only a decade between all three adaptations these feel like three very different interpretations of the scene, with different chronological, historical and physical settings and fairly different performances and tones. But all three, I think, hit on what makes this scene so perennially appealing: the combination of anticipation, disappointment, and promise. Some of the greatest pleasure is pleasure either anticipated or deferred and this scene offers both. Readers get the realized pleasure of the emotional declaration they have surely been anticipating since the moment Elizabeth and Darcy met combined with the thrill of knowing they’ll get to watch the romance continue to unfold because that proposal? They’ll have to wait for it.