A History of Zines

If you’ve ever been into an indie bookstore or cruised around at a comic convention, you’ve likely seen or flipped through a zine. Zines (pronounced ZEEN) have been around since the early 20th century, and have been an enormous part of underground and non-commercial publication. Zines are characteristically cheap to make, often photocopied, and have a distinctly “DIY” look. Often, they represent the voices of people on the fringes, and their content is hyper local.

As far as content goes, zines can feature poetry, art, collage, interviews, comics, and more. Your local small press can roll out zines covering topics from anarchistic gatherings in your area, to comics about police brutality, to tutorials on how to build your own garden boxes. You can even find artistic zines online today, featuring art and artists from all around the world.

Zines have travelled a long way before arriving on your bookshelf or computer screen…so let’s take a little look at where they’ve been!

The 1930s and ’40s

The very first zine dates back to May of 1930 in the USA. A little publication called The Comet was first created by the Science Correspondence Club. The letter section of the zine was a prominent feature, where fans discussed science as well as science fiction.

At this time, photocopiers had not yet been invented. Enter the mimeograph, also known as a stencil duplicator. This machine was invented in the 1800s and remained in use until the 1960s and ’70s when it was slowly replaced by the photocopier. It was not ideal for large editions, but it was perfect for the pulp fan magazines of the 1940s–60s.

The 1940s saw a boom in the science fiction fanzine culture. In October of 1940, Russ Chauvenet coined the term fanzine in his sci-fi publication Detours. A number of authors of the day created zines, including Ray Bradbury, Jack Williamson, and Robert A. Heinlein.

Additionally, the 1940s saw the first ever queer fanzine. A woman named Edythe Eyde (also known as Lisa Ben, an anagram of “lesbian”) typed out the first copy of Vice Versa in June of 1947, creating a total of nine issues before ending it the following year. The publication was free, and Lisa Ben mailed them to friends as well as hand delivering them.

In 1949, the Xerox Corporation introduced the first xerographic copier, and “xeroxing” was officially born.

The 1950s and ’60s: Folk Zines, Comics, and Star Trek

Several popular zines centring folk music culture emerged during the 1950s. Lee Hoffman was a prominent figure who published several science fiction zines as well as folk zines such as Bad Day at Lime Rock, Caravan, and Quandry.

Artists such as Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, and Jay Lynch began to find their voices through fanzines, inspired by magazines such as Mad and Cracked. These artists went on to found the underground comics movement that changed the face of the comics industry.

While folk zines were still around in the 1960s, rock and roll zines also took the stage. Paul Williams’s zine Crawdaddy! was the most popular of these, but it soon became popular enough to turn legit and become a full-on magazine.

Spockanalia was the first Star Trek zine in 1967, and it was wildly popular. The second issue featured letters from the cast, including Leonard Nimoy.

In 1968, Star Trek was to be cancelled after two seasons, but through fan lobbying (part of which was organized through fan zines), the fans were able to get the show back on the air for another year.

The 1970s and ’80s: Punk Zines and the DIY Movement

Copy shops were now widely available in the 1970s, changing zine production forever. Now, zinesters were able to make many copies quickly and cheaply, and the look of zines changed along with it.

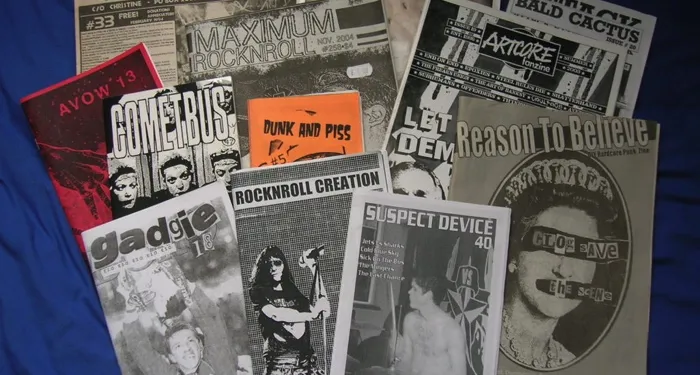

The punk scene became the main hub of zine culture during the ’70s. Zines took on a grungy, do-it-yourself style. Some of the most popular of these were Sniffin’ Glue, 48 Thrills, and Bondage. Most works came out of New York, L.A., and London. Punk zines continued well into the 1980s.

The 1990s and 2000s: Riot Grrrl and Queercore

Riot Grrrl, an underground feminist punk movement, came about in the 1990s. With this movement came a huge sweep of political zines that spread the feminist manifesto.

Queercore (AKA homocore) is another offshoot of anarcho-punk subculture, this one aimed at critiquing homophobia within the genre and society as a whole. QZAP (Queer Zine Archive Project) was first launched in 2003 in an effort to preserve as many queer zines as possible.

2010s and Beyond: What’s Next?

Zines are still all the rage, both in digital and DIY physical forms. There are now zine fests, libraries collect zines and bookstores sell them. The POC Zine Project was created in 2015 to archive zines written by people of colour.

The zine is as popular today as it ever has been. It remains an important part of subcultural movements and underground press for marginalized voices. Anybody can make a zine… that’s the best part!