Author Cassandra Khaw and the Compassion of Horror

Many speculative fiction readers love science fiction and fantasy, but flinch from horror. If you love speculative fiction, however, author Cassandra Khaw makes a compelling argument for why you should also be reading horror: it could make you a better human.

“If fantasy and science fiction can open our eyes to different ideals and worldviews, different interpretations of our present and our future, then horror is almost mandatory,” she said. “Horror opens us up as humans and demands that we investigate the impulses that we all have, but most of us suppress.”

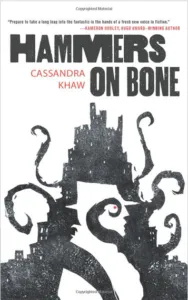

I read Khaw’s 2016 novella, Hammers on Bone, last year while I was on a Lovecraft retelling kick. But Hammers on Bone was something else entirely — it veered into noir and horror. Not the arms-length, emotionally-distant sort of horror Lovecraft used, but full-on, squishy, visceral terror.

John Persons, Khaw’s protagonist, is a modern P.I.. He is hired by a little boy to kill an abusive stepfather. Why Persons? Because neither he nor the stepdad are human. They’re Elder Things. Persons (who I should point out, is a likable, sympathetic character) is wearing someone else’s body like a suit.

It’s gruesome, it’s compelling, and it is also strangely compassionate.

Gore and compassion

Khaw doesn’t shy away from gore, and it’s something she does purposefully, and with a lot of respect for the human body — using scent and taste — senses the horror film industry doesn’t have access to.

Khaw doesn’t shy away from gore, and it’s something she does purposefully, and with a lot of respect for the human body — using scent and taste — senses the horror film industry doesn’t have access to.

Strangely enough, it’s a bid for creating a little kindness in the world. If readers see how difficult it is to kill and to die, Khaw hopes they might respect suffering more.

“I think Hollywood and mass media doesn’t really respect the idea of death. It’s always buckets of blood and almost glamorous,” she said. “In reality, when someone dies, it’s this slow, stuttering, painful thing.”

It’s the smell and taste of bodily fluids. It’s suffocating slowly in your own lungs. It’s an organ giving out. And it’s something we will all experience.

“I kind of want to remind people of that, and in some weird way, warn people away from the idea that death is easy. And I’m hoping it sticks, so the next time they hear that someone got hurt on the news, they’re not just going to brush it off,” said Khaw.

Khaw based the book on a different kind of horror; two children she heard of who’d been abused for years, while no one around them said anything.

“It just kind of hit me how horrifying that is, that if we see it happening on a daily basis, slowly and surely, we just normalize it and expect it to be ok,” said Khaw. “Because the alternative thought — the idea that it might not be okay — frightens people in general.”

Games and novels

Khaw lives in Malaysia, and has traveled the world in her career as a tech and games journalist. She’s a huge reader — one of her favorite authors is Frances Hardinge. (I refer you to this Twitter thread.) She writes a lot; one of her most recent projects is a video game, the award-winning She Remembered Caterpillars, a “color matching, fungi-punk, puzzle game that is about injecting cute into invasive brain surgery.”

The process of writing the game was much more collaborative than writing fiction.

“If novel writing is this solo project where you just kind of hide in the woods and bang on a keyboard for six weeks, writing for games is stirring around trying to wedge words into more complicated pieces and hoping it looks great instead of causing the whole machine to fall down,” she said.

It also involved fewer words; Khaw’s first script for the game was 40 pages long, and had to be cut down to about five. Much of the story ended up being told through the art.

“Video game writing reminded me that very word, every pixel, is completely open to interpretation. This applies to anything you touch. So video writing has made me at least marginally more self-aware in terms of my writing elsewhere.”

Making monsters

Right now, Khaw is working on a piece about mermaids, a follow-up to a recent short story, And In Our Daughters, We Find a Voice, published in The Dark Magazine. It’s a retelling of The Little Mermaid, in its own way.

“The story basically started with me seeing an image, this comic that said, why does anyone expect Ariel to give birth to babies, wouldn’t she spawn eggs,” said Khaw. “And that kind of went into a horrible place after that.”

Khaw’s creatures, like Lovecraft’s, and HR Giger’s, are utterly inhuman. She spends a great deal of time creating them; understanding their bodies, their civilizations, and their needs. It’s another step toward compassion.

“Human beings, when we see something that looks like us, our first thought is to impose our own views and values and ethics on it,” she said, “whereas when confronted with something that is genuinely alien, all of our preconceptions just stop because we have no idea how to function anymore.”

Working in Lovecraft’s world

A Song For Quiet, Khaw’s follow-up to Hammers on Bone, will be released later this year by Tor.com, bringing back John Persons and all the eldritch horror that comes with him. This book will also introduce one of H.P. Lovecraft’s favorite settings: Arkham.

Many authors have played in the sandbox of Lovecraft’s world, making it their own. Many have also embraced his creatures but rejected the man himself — Lovecraft was notoriously racist, sexist, and xenophobic.

When I asked Khaw how she navigates his world as an author of color, she replied that working in that world felt natural.

“It feels a lot like writing as a queer woman of color from a third world nation that half of the people I meet still don’t actually know exists,” she said. “In a way, writing Lovecraft’s world kind of feels like just being myself and marching into the West and just seeing the — not necessarily bigotry — but just the culture that’s stacked up against you.”

Hungry for more of Khaw’s work? You can find her other books and stories here.