Long Live the ZORA Canon: 100 Great Books by African American Women

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

It isn’t hyperbole to suggest that I’ve been obsessed with “The Canon” ever since I went through my senior year high school English class without reading a single book by an author of color. That year was followed by me attending Barnard College of Columbia University. Both Barnard and Columbia (which are sort of one and the same; it’s messy and hard to explain) have English departments who follow the “traditional” “English” “canon.”

Why all the quotation marks? Well, it is important to acknowledge that so much of what we think of as the Capital-C Canon is completely arbitrary, not to mention seeped in elitism. And racism, sexism, and a whole bunch of other -isms that are dominant in our culture. The canon as a selection of works aims to represent those that are the pinnacle of artistry in the literary tradition. It is often thought to include works like Shakespeare, Beowulf, Paradise Lost, Homer, and so on and so forth. You get the idea. And hey, some of this stuff is good. I might even call it great. But what it is severely lacking is any color at all. Along with any meaningful amount of gender diversity.

The only author of color (and Black author) often considered “canonical” alongside these people is Toni Morrison. This is totally correct, given her lifelong creation of epic literature. But she is surely not the only Black woman to merit “canonical” status.

The only author of color (and Black author) often considered “canonical” alongside these people is Toni Morrison. This is totally correct, given her lifelong creation of epic literature. But she is surely not the only Black woman to merit “canonical” status.

A canon is a way of saying “this is what has shaped our culture.” It is a message to further generations telling them what to study, what to note historically as important, and more. But, as the ZORA editors note in their introduction, the ZORA Canon is “less to prove the value of Black women’s voices and their humanity than to ‘go about challenging the work of figuring out what this space would mean for us’.” I had been fighting for people to see that work by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color were somehow worthy of the illustrious Western canon. But the ZORA team makes a poignant statement and suggests that one’s “humanity” and “voices” shouldn’t need to be proven as good.

They’re right: it is exhausting to fight for the powers that be to hear the unheard voices. What the ZORA team does instead is say: Black women can have a canon all their own, and here it is.

A canon is a way of saying “this is what has shaped our culture.” It is a message to further generations telling them what to study, what to note historically as important, and more. But, as the ZORA editors note in their introduction, the ZORA Canon is “less to prove the value of Black women’s voices and their humanity than to ‘go about challenging the work of figuring out what this space would mean for us’.” I had been fighting for people to see that work by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color were somehow worthy of the illustrious Western canon. But the ZORA team makes a poignant statement and suggests that one’s “humanity” and “voices” shouldn’t need to be proven as good.

They’re right: it is exhausting to fight for the powers that be to hear the unheard voices. What the ZORA team does instead is say: Black women can have a canon all their own, and here it is.

Some of my favorite picks from the list include N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season, Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, and Ann Petry’s The Street. A small part of me is sad—how much more seen and validated would I have felt, had I been required to read some of these women when I was 17? But mostly, I am joyous that the ZORA Canon exists now as a historical and cultural bookmark. I hope teachers and professors everywhere use this as a reference and a challenge to expand not just their classroom curriculum, but their classroom’s experiences as a whole.

Thank you so much to the entire ZORA team for putting in the work to make this a reality.

Some of my favorite picks from the list include N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season, Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, and Ann Petry’s The Street. A small part of me is sad—how much more seen and validated would I have felt, had I been required to read some of these women when I was 17? But mostly, I am joyous that the ZORA Canon exists now as a historical and cultural bookmark. I hope teachers and professors everywhere use this as a reference and a challenge to expand not just their classroom curriculum, but their classroom’s experiences as a whole.

Thank you so much to the entire ZORA team for putting in the work to make this a reality.

The only author of color (and Black author) often considered “canonical” alongside these people is Toni Morrison. This is totally correct, given her lifelong creation of epic literature. But she is surely not the only Black woman to merit “canonical” status.

The only author of color (and Black author) often considered “canonical” alongside these people is Toni Morrison. This is totally correct, given her lifelong creation of epic literature. But she is surely not the only Black woman to merit “canonical” status.

Why Does This Matter Anyway?

It can be hard to believe that something as esoteric as the academic literature canon matters in our everyday lives. But just one part of the answer is that the canon dictates what nearly every child learns about in school. From elementary to university learning, the societal “canon” sets forth what is important and what is worth studying. What kind of message does this send to students of color about their creations? That they are not worthy of greatness, or massive cultural impact? Also worrying is: what does this tell white students? Just last year at Columbia, a student went on a racist rant espousing the virtues of whiteness. “White people are the best thing that ever happened in the world,” he said. And honestly, he attends a college that consistently tells him that his beliefs are true. He learns mostly about great white people in his required English, Art, and Music classes in a predominantly white college space. These beliefs left unchallenged diminish the role of the University as one where some sort of “objective” knowledge can be gained. I tried to suggest a change in Barnard’s curriculum, but felt resistance at nearly every turn, save for some amazing faculty on my side. It honestly felt hopeless. I didn’t want to get rid of Shakespeare, I just want to add a little James Baldwin to the mix. Was that really asking too much? Now, I roll my eyes whenever someone mentions the Capital-C Canon at all. But then I came across something that took my breath away.The ZORA Canon: 100 Best Books By African American Women Writers

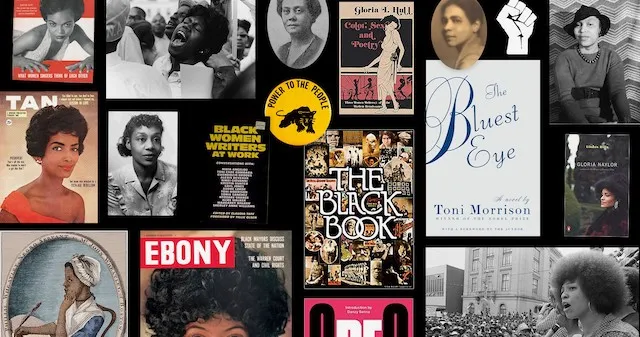

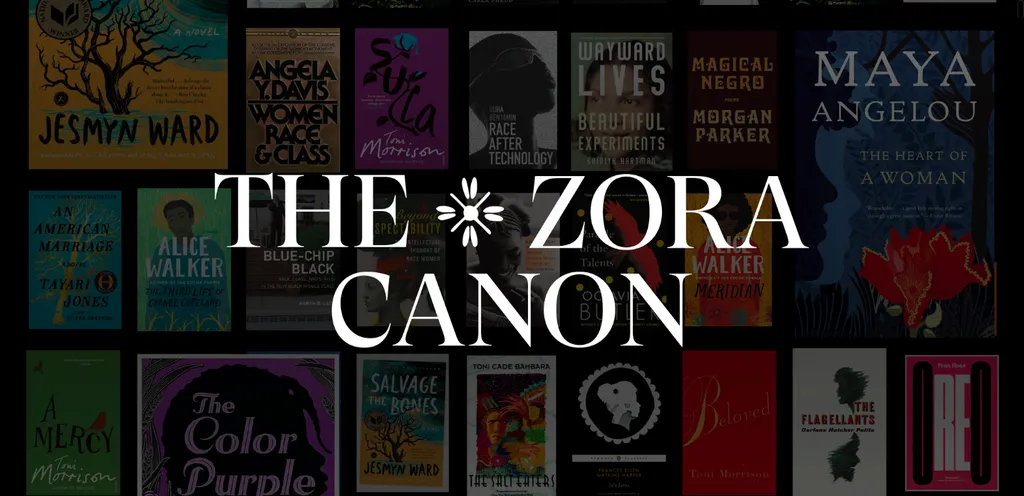

ZORA, named for the groundbreaking Black writer Zora Neale Hurston (shoutout to another Barnard alum!), is a publication on Medium created by women of color. Just today, the editors released The ZORA Canon, a selection of 100 works by African American women. And let me tell you, it is a beauty. A canon is a way of saying “this is what has shaped our culture.” It is a message to further generations telling them what to study, what to note historically as important, and more. But, as the ZORA editors note in their introduction, the ZORA Canon is “less to prove the value of Black women’s voices and their humanity than to ‘go about challenging the work of figuring out what this space would mean for us’.” I had been fighting for people to see that work by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color were somehow worthy of the illustrious Western canon. But the ZORA team makes a poignant statement and suggests that one’s “humanity” and “voices” shouldn’t need to be proven as good.

They’re right: it is exhausting to fight for the powers that be to hear the unheard voices. What the ZORA team does instead is say: Black women can have a canon all their own, and here it is.

A canon is a way of saying “this is what has shaped our culture.” It is a message to further generations telling them what to study, what to note historically as important, and more. But, as the ZORA editors note in their introduction, the ZORA Canon is “less to prove the value of Black women’s voices and their humanity than to ‘go about challenging the work of figuring out what this space would mean for us’.” I had been fighting for people to see that work by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color were somehow worthy of the illustrious Western canon. But the ZORA team makes a poignant statement and suggests that one’s “humanity” and “voices” shouldn’t need to be proven as good.

They’re right: it is exhausting to fight for the powers that be to hear the unheard voices. What the ZORA team does instead is say: Black women can have a canon all their own, and here it is.

The List Itself

The editors remark that the ZORA canon “is a list of 100 masterworks, spanning 160 years of African American women’s literature, divided into sections from pre-emancipation to the present, including fiction and nonfiction, novels, plays, anthologies, and poetry collections and ranging in subject matter from the historical to the personal (and sometimes both at once). Taken together, the works don’t just make up a novel canon; they form a revealing mosaic of the Black American experience during the time period. They’re also just great reads.” Some of my favorite picks from the list include N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season, Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, and Ann Petry’s The Street. A small part of me is sad—how much more seen and validated would I have felt, had I been required to read some of these women when I was 17? But mostly, I am joyous that the ZORA Canon exists now as a historical and cultural bookmark. I hope teachers and professors everywhere use this as a reference and a challenge to expand not just their classroom curriculum, but their classroom’s experiences as a whole.

Thank you so much to the entire ZORA team for putting in the work to make this a reality.

Some of my favorite picks from the list include N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season, Tayari Jones’s An American Marriage, and Ann Petry’s The Street. A small part of me is sad—how much more seen and validated would I have felt, had I been required to read some of these women when I was 17? But mostly, I am joyous that the ZORA Canon exists now as a historical and cultural bookmark. I hope teachers and professors everywhere use this as a reference and a challenge to expand not just their classroom curriculum, but their classroom’s experiences as a whole.

Thank you so much to the entire ZORA team for putting in the work to make this a reality.