Should We be Okay with the New ALADDIN?

Though its fantastical nature was obvious to me, I was still disheartened as I learned of Aladdin’s many irresponsible artistic licenses. Imagine my utter despair when, in high school, I learned of Aladdin’s many anachronisms, its Anglicization and bastardization of the original narrative from Arabian Nights, which, by the way, was The Thousand and One Nights first, and then a white guy decided to make it even more Orientalist as he rewrote it. How my beloved Robin Williams contributed to Arab stereotypes. Or the fact that it was supposed to be set in Afghanistan, but given the recent Gulf War, Disney decided to name a fictional city, Agrabah, instead.

The problem with Disney’s Aladdin was not its fairytale nature. Its fantasy is, as I’ve said, obvious. When the Genie said, “You ain’t never had a friend like me,” he wasn’t lying, and I wanted a friend like him. It was all the other stuff, taken in stride, that was the problem. And you know what? I didn’t care about that at all. I knew about all its shittiness and I loved it anyway. I still love it. I still know every word to every New Orleans–style song, know when to do the Fosse-style jazz lunges in the Cave of Wonders, still tell dudes who ask me if I’m dressed like Jasmine on purpose that their beards are “sooooo twisted.”Because of my nostalgia for the “original” 1992 cartoon, I was REAL FUCKIN’ RELUCTANT to see this new Disney remake. I had a lot of questions: Number one, how dare you? Without Robin Williams. Number two, I have already made peace with your former fuck-ups. Are you going to do better this time? Number three, what all are you going to retell? Number four, where are you going to have this movie “set”?

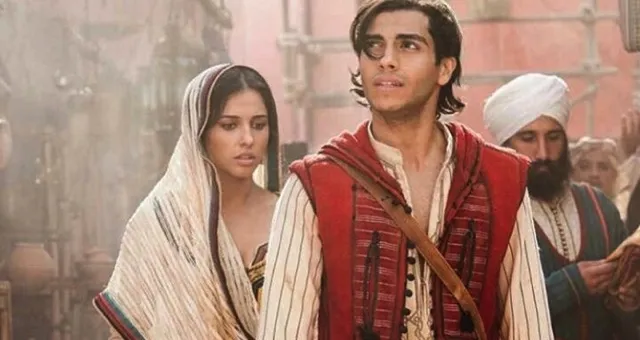

As I watched trailer after trailer, my reluctance started to wane. They cast actors who were actually from the region, however broad that region was. (I have jokingly called it Planet Egyptland.) They revised the “Arabian Nights” lyrics to say “chaotic” instead of “barbaric, but hey, it’s home!” Will Smith. Lookin’ all fine. Okay, I’ll give it a shot. In preparation, I read Aladdin: A New Translation translated by Yasmine Seale and edited by Paulo Lemos Horta. To be totally honest, it might as well have been the first time I ever read the story itself. Sure, I had children’s versions, and I read 1001 Nights, but in some versions of that text, Aladdin doesn’t even appear. When I read Paulo Lemos Horta’s introduction, I realized that 1001 Nights and the story of Aladdin are in their natures ever-changing, as fairytales do. And it made me a lot more comfortable with straight-up disregarding the inconsistencies in the myriad retellings that I’ve read and seen.

In preparation, I read Aladdin: A New Translation translated by Yasmine Seale and edited by Paulo Lemos Horta. To be totally honest, it might as well have been the first time I ever read the story itself. Sure, I had children’s versions, and I read 1001 Nights, but in some versions of that text, Aladdin doesn’t even appear. When I read Paulo Lemos Horta’s introduction, I realized that 1001 Nights and the story of Aladdin are in their natures ever-changing, as fairytales do. And it made me a lot more comfortable with straight-up disregarding the inconsistencies in the myriad retellings that I’ve read and seen.

For example, Aladdin’s original setting is in China, though the story was allegedly passed to a Frenchman through a Syrian traveler who spoke French. (And at the time, Lebanon would have been a part of Syria—IN YOUR FACE, HIGH SCHOOLERS.) So, no Agrabah. And, in the 2019 film, “Ababwa” which is the fantasy land that Aladdin invents, and which “Prince Ali” is supposed to rule, is labeled on the map as “FANTASY LAND” by the genie! If that makes your brain be like, Okay, but wait, what now? Then, EXACTLY.

Aladdin is first and foremost a fairytale spawned from an oral tradition. There are many inconsistencies among its iterations, but that’s how oral traditions work. The fish gets a little bigger every time. And depending on to whom you’re telling the story, you change it a little. Here are some changes that the new Aladdin made that I think improved it. (That’s not to say that the New Translation isn’t the best thing ever told—it totally is. But, depending on the audience…perfection is kind of subjective.)Aladdin Himself

I loved Aladdin in the cartoon because he was scrappy and he had a big heart. Never mind that he was a liar and a thief—that was tertiary to me. In the original story, too, our protagonist is, like, not that protagonisty. He’s kind of lazy when he’s a kid, and he’s tricked easily. In the new movie, he’s less dishonest, way less angsty towards his father-figure genie (like he is in the cartoon), and he’s also stupid hot, so that doesn’t hurt. Plus, Aladdin is a stroke-of-luck bootstrapping-oneself tale, according to this retelling, and what American doesn’t love an underdog success story?The Genie

You know who else is stupid hot? Will Smith. And he’s funny, too! He and the team of the new Aladdin made a great choice in having this character be an homage to the cartoon without remaking Robin Williams’s character. Let’s be honest, no one can out–Robin Williams Robin Williams! And while we’re talking about the genie, the jinni (as the new translation I mentioned above spells the Arabic-to-English transliteration) has no personality. I’m not being cruel: he literally just follows orders. He refers to himself as the slave of the lamp—and by the way, there is also a jinni of the ring, which is never mentioned in either Disney rendition. He also has no personality. In fact, Aladdin’s mother refers to both jinnis as demons, which, in the Disney-fied versions, is just not true. Transforming the jinni into a magical friend was THE MOVE. Seriously, the genie steals the show. Here’s a maybe-problem, though. Will Smith, an incredibly successful Black American actor, being cast as the genie is both acknowledging the cartoon’s cultural appropriation (ain’t no big band jazz in the Middle East 400s—or whenever it’s set, because it’s impossible to tell), while also kind of acknowledging an entire ethnic group’s enslavement. It’s an entirely American retelling. I don’t hate it. But. I think it’s a little problematic, because why does the Black character have to be the enslaved one, and need a lighter/white-passing one to free him…? Also, is this a Magical Negro trope?But also, I really loved Will Smith in that role. It’s problematic, but his performance is not. Because now? That parade makes SENSE. Aladdin magically break dancing? THAT MAKES SENSE. And so does the anachronism, because the genie is magic and exists outside of space and time. (But also, is this an excuse to rationalize the way that the cartoon originally played out?)

Please note: I say NONE of this to diminish Will Smith’s performance. Honestly, he had big shoes to fill, and he was literally amazing.The Women

Speaking of existing outside space and time, let’s talk about women in this movie. Not only is Princess Jasmine not a prize to be won, but in the new retelling, she has agency over her own life, which is pretty nice, and a much-needed adjustment to fairytale narratives. She also has a handmaid who gets to marry the genie, and we get to see female friendship happen in a Disney film (eyooooo!). In direct contrast, in the text Aladdin, Princess Badr Al-Budur is essentially a Stephen King character to be acted upon by the male protagonist. (Booo.) So, really, even the 1992 was an improvement upon that chalk outline of a character. Again, I’m not saying that to be cruel; it’s just how her character was written—and I’ll revisit the reasons for that in just a second.

The thing to remember about Aladdin, truly, is that his is just one of many stories in 1001 Nights. To recap the premise very quickly, King Shahryar’s wife cheats on him A BUNCH and he cuts off her head. To retaliate on all of womanhood, he takes a new bride each night, and then beheads her in the morning. Shahrazad, the cunning daughter of his grand vizier, decides to fall on her sword because she does not want any more women to die, and she marries him. She tells him a story the first night, but says she’s too tired to finish, and will finish in the morning. King Shahryar says he’ll probably cut off her head by then, but he doesn’t. She continues this cliffhanger M.O. until he’s actually in love with her. Aladdin’s story was just ONE of the many that enabled Shahrazad to save her own life (and many others). I loved the retelling by Yasmine Seale, particularly because it showed the motivations of telling the story the problematic way: Shahrazad was saving her own life. She had to make the somewhat lazy yet lucky Aladdin the protagonist so Shahryar would identify with him. She had to make Badr al-Budur a simple, devoted, loving wife with no ambitions of her own because she was brain-ninja-ing Shahryar into thinking that of herself. Frame stories, man. What a vital extra lens. Plus, it supports my argument that the story has to be tailored to its audience for it to be received well. In the written retelling, Yasmine Seale does just that. She provides enough of the 1001 Nights construct to situate its narrative as sliiiiiightly manipulative, but for all the right reasons.Let’s talk about how the 1992 cartoon robbed Shahrazad of her victory and instead gave that story to a stereotyped merchant/charlatan trying to hustle a coffeemaker. (DEEP FROWN.)

Let’s talk about how the 2019 movie gave her story to the genie to entertain his adorable little misbehaving kids. (Less frown.) (I mean, that is, after all, the purpose of a fairytale, right? To entertain kids, and to keep them from getting themselves killed.)

But really, we’re here to answer the question: Should we like the new Aladdin? Which retelling is right? I think it depends. Story is amorphous, and that’s kind of what its listeners love about it. We can easily see ourselves in a narrative arc, if it’s a good one. Aladdin is a fairytale. And it’s okay, in my opinion, for it to be retold ad infinitum, if it is each time improved and tailored for a specific audience…even if I am not its target audience…and even if I believe in my heart of hearts that I should be the key demographic. For all those reasons, I have come to the conclusion, Yeah, totally go see the new Aladdin! More than the film, though, I definitely recommend reading Yasmine Seale’s Aladdin: A New Translation. It’s written beautifully, every line is poetry, and it’s as close to an original as we have in the English language. It’s also REALLY different. The other thing to remember is that many things can be true. I loved the 1992 Aladdin, but it certainly had its flaws. That doesn’t make me like it any less. And that’s a problem, too. Though the new movie is a dramatic improvement, the West still affects all narratives. Disney can’t dismantle the system, and trying likely perpetuates it…but what’s the alternative? Stop telling these stories? Erase their history? That seems even more dangerous. What do you think?