A Love Letter To Books That Tell You How They End

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

So you’re reading a book. And right at the beginning, it says something about how the mother dies. You’re sitting right there. Does the novel know that it just told you what would happen? Won’t that ruin it? Won’t the emotional impact not hit as hard since you know exactly what’s coming?

If the writer knows what they’re doing, as they sometimes do, about 300 pages later you’ll be sobbing into your book on a plane, and thinking to yourself, “But I knew the mom would die. The book literally told me that the mom would die. Why is this hitting me so hard?”

I have a special place in my heart for novelists who are so talented that they can give it all away right at the start and have it not matter at all, because they are so darn good at their job that around three-fourths of the way through, you’ll have either forgotten that you know how it all ends, or they’ll have raised your hopes that somehow the plan will work, or the characters will somehow survive.

Not to mention the books where you know that the protagonist is alive at the end because they’re narrating past events, and yet you’re still in nail-biting suspense about whether they’ll make it through anything they’re describing. Or my dad recently told me about a book that informed him that by the end, he would be crying for a certain character, and he protested with a scoff, “No, I won’t,” and then found himself crying over…that exact character. Of course. And then there are the books that tell you that you know what happens at the end but then push further past the scene you’ve seen, or reveal that you misunderstood something, that you were wrong somehow in your expectations.

If the writer knows what they’re doing, as they sometimes do, about 300 pages later you’ll be sobbing into your book on a plane, and thinking to yourself, “But I knew the mom would die. The book literally told me that the mom would die. Why is this hitting me so hard?”

I have a special place in my heart for novelists who are so talented that they can give it all away right at the start and have it not matter at all, because they are so darn good at their job that around three-fourths of the way through, you’ll have either forgotten that you know how it all ends, or they’ll have raised your hopes that somehow the plan will work, or the characters will somehow survive.

Not to mention the books where you know that the protagonist is alive at the end because they’re narrating past events, and yet you’re still in nail-biting suspense about whether they’ll make it through anything they’re describing. Or my dad recently told me about a book that informed him that by the end, he would be crying for a certain character, and he protested with a scoff, “No, I won’t,” and then found himself crying over…that exact character. Of course. And then there are the books that tell you that you know what happens at the end but then push further past the scene you’ve seen, or reveal that you misunderstood something, that you were wrong somehow in your expectations.

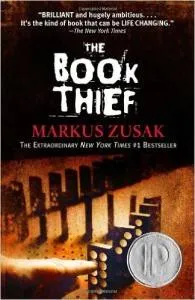

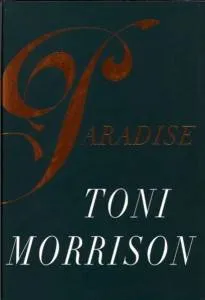

I love these books. There’s something very artful and skillful about books that can tell you the ending and still accomplish the suspension of disbelief necessary to keep you pulled into the story. It’s not quite foreshadowing: it’s more than that. More direct. Toni Morrison’s Paradise begins: “They shoot the white girl first. With the rest they can take their time.” Markus Zuzak’s Death, narrator of The Book Thief, informs us before he even starts telling Liesel’s story that the third time he saw her, she was on a bombed-out, ash-filled street, and she was howling.

There’s a special magic to these novels. I’m not the only one who thinks so—I even know some readers who will skip to the ending of a novel, read it first, and then begin. And there are many novels where rereading it improves it, giving more detail and nuance to the twisting of events, to the small bits of foreshadowing or development. There’s almost a sense of time travel to rereading a book.

By telling the ending at the beginning, an author achieves a little bit of that rereading magic right from the start. There’s a reason that giving it all away has such a positive impact on a novel, if it’s done right. I think it gets to a sense that stories are bigger than the events they carry with them.

Perhaps the best writers know that the events themselves are not the story: it’s the journey, the full knowledge of the characters and how they got there. By beginning with the end, it’s like the author is whispering to us: “This is what happens. But don’t worry. It’s not the important part.”

I love these books. There’s something very artful and skillful about books that can tell you the ending and still accomplish the suspension of disbelief necessary to keep you pulled into the story. It’s not quite foreshadowing: it’s more than that. More direct. Toni Morrison’s Paradise begins: “They shoot the white girl first. With the rest they can take their time.” Markus Zuzak’s Death, narrator of The Book Thief, informs us before he even starts telling Liesel’s story that the third time he saw her, she was on a bombed-out, ash-filled street, and she was howling.

There’s a special magic to these novels. I’m not the only one who thinks so—I even know some readers who will skip to the ending of a novel, read it first, and then begin. And there are many novels where rereading it improves it, giving more detail and nuance to the twisting of events, to the small bits of foreshadowing or development. There’s almost a sense of time travel to rereading a book.

By telling the ending at the beginning, an author achieves a little bit of that rereading magic right from the start. There’s a reason that giving it all away has such a positive impact on a novel, if it’s done right. I think it gets to a sense that stories are bigger than the events they carry with them.

Perhaps the best writers know that the events themselves are not the story: it’s the journey, the full knowledge of the characters and how they got there. By beginning with the end, it’s like the author is whispering to us: “This is what happens. But don’t worry. It’s not the important part.”

If the writer knows what they’re doing, as they sometimes do, about 300 pages later you’ll be sobbing into your book on a plane, and thinking to yourself, “But I knew the mom would die. The book literally told me that the mom would die. Why is this hitting me so hard?”

I have a special place in my heart for novelists who are so talented that they can give it all away right at the start and have it not matter at all, because they are so darn good at their job that around three-fourths of the way through, you’ll have either forgotten that you know how it all ends, or they’ll have raised your hopes that somehow the plan will work, or the characters will somehow survive.

Not to mention the books where you know that the protagonist is alive at the end because they’re narrating past events, and yet you’re still in nail-biting suspense about whether they’ll make it through anything they’re describing. Or my dad recently told me about a book that informed him that by the end, he would be crying for a certain character, and he protested with a scoff, “No, I won’t,” and then found himself crying over…that exact character. Of course. And then there are the books that tell you that you know what happens at the end but then push further past the scene you’ve seen, or reveal that you misunderstood something, that you were wrong somehow in your expectations.

If the writer knows what they’re doing, as they sometimes do, about 300 pages later you’ll be sobbing into your book on a plane, and thinking to yourself, “But I knew the mom would die. The book literally told me that the mom would die. Why is this hitting me so hard?”

I have a special place in my heart for novelists who are so talented that they can give it all away right at the start and have it not matter at all, because they are so darn good at their job that around three-fourths of the way through, you’ll have either forgotten that you know how it all ends, or they’ll have raised your hopes that somehow the plan will work, or the characters will somehow survive.

Not to mention the books where you know that the protagonist is alive at the end because they’re narrating past events, and yet you’re still in nail-biting suspense about whether they’ll make it through anything they’re describing. Or my dad recently told me about a book that informed him that by the end, he would be crying for a certain character, and he protested with a scoff, “No, I won’t,” and then found himself crying over…that exact character. Of course. And then there are the books that tell you that you know what happens at the end but then push further past the scene you’ve seen, or reveal that you misunderstood something, that you were wrong somehow in your expectations.

I love these books. There’s something very artful and skillful about books that can tell you the ending and still accomplish the suspension of disbelief necessary to keep you pulled into the story. It’s not quite foreshadowing: it’s more than that. More direct. Toni Morrison’s Paradise begins: “They shoot the white girl first. With the rest they can take their time.” Markus Zuzak’s Death, narrator of The Book Thief, informs us before he even starts telling Liesel’s story that the third time he saw her, she was on a bombed-out, ash-filled street, and she was howling.

There’s a special magic to these novels. I’m not the only one who thinks so—I even know some readers who will skip to the ending of a novel, read it first, and then begin. And there are many novels where rereading it improves it, giving more detail and nuance to the twisting of events, to the small bits of foreshadowing or development. There’s almost a sense of time travel to rereading a book.

By telling the ending at the beginning, an author achieves a little bit of that rereading magic right from the start. There’s a reason that giving it all away has such a positive impact on a novel, if it’s done right. I think it gets to a sense that stories are bigger than the events they carry with them.

Perhaps the best writers know that the events themselves are not the story: it’s the journey, the full knowledge of the characters and how they got there. By beginning with the end, it’s like the author is whispering to us: “This is what happens. But don’t worry. It’s not the important part.”

I love these books. There’s something very artful and skillful about books that can tell you the ending and still accomplish the suspension of disbelief necessary to keep you pulled into the story. It’s not quite foreshadowing: it’s more than that. More direct. Toni Morrison’s Paradise begins: “They shoot the white girl first. With the rest they can take their time.” Markus Zuzak’s Death, narrator of The Book Thief, informs us before he even starts telling Liesel’s story that the third time he saw her, she was on a bombed-out, ash-filled street, and she was howling.

There’s a special magic to these novels. I’m not the only one who thinks so—I even know some readers who will skip to the ending of a novel, read it first, and then begin. And there are many novels where rereading it improves it, giving more detail and nuance to the twisting of events, to the small bits of foreshadowing or development. There’s almost a sense of time travel to rereading a book.

By telling the ending at the beginning, an author achieves a little bit of that rereading magic right from the start. There’s a reason that giving it all away has such a positive impact on a novel, if it’s done right. I think it gets to a sense that stories are bigger than the events they carry with them.

Perhaps the best writers know that the events themselves are not the story: it’s the journey, the full knowledge of the characters and how they got there. By beginning with the end, it’s like the author is whispering to us: “This is what happens. But don’t worry. It’s not the important part.”