How to Read Problematic Baby Books

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

When I’m reading a book to my two year old, I don’t skip over words. I don’t summarize or rush through. I want my kid to hear different voices in these stories. There are times, though, that I feel like I want to change some of the language. It seems wrong to read certain problematic lines from baby books out loud to him. I usually end up reading the line or situation as it’s written and talking about it right afterwards. He’s a little young to engage like that, but he remembers the moments that I stop at the next time we read it, which suggests to me that it’s not a wasted effort. I want to make sure he’s thinks seriously about the media he consumes.

One subtle example is The Little Engine that Could by Watty Piper. My son asks me to read that book over and over again, and the book itself is kind of annoying because the language is so repetitive. The toys and clown repeat this same line to each train that comes by: “please…won’t you please pull our train over the mountain? Our engine has broken down, and the boys and girls on the other side won’t have any toys to play with or good food to eat unless you help us.” I can’t help but wonder why the “boys and girls” phrasing is in there over and over and over. It feels like you’re just being beat in the head with it. I always just say “kids,” partially just to shorten it, but also because I don’t see the point in differentiating gender in that moment. Is it just showing that some toys are for girls and others are for boys? Or to just be hyper-obsessed with a gender binary? It might just be that it’s an old book, but challenging this type of language matters.

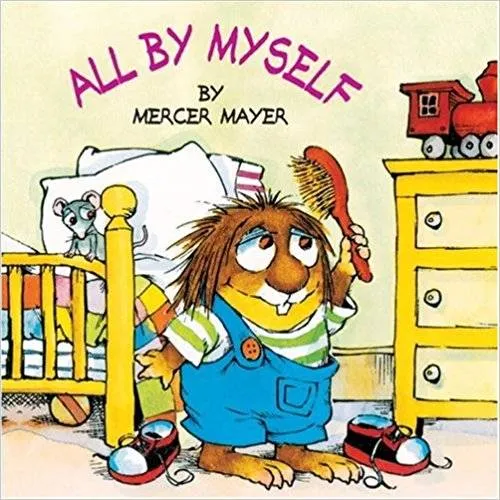

In All By Myself by Mercer Mayer, one of the Litter Critter books, the narrator offers up a variety of things that he can do now that he’s bigger. The book has a cute message about independence, but certain parts are awkward. Midway through, he says, “I can help Dad trim a bush or ice a cake for Mom.” Just like the “boys and girls” phrase in Piper’s book, I’m left wondering why these jobs are so boringly gendered. Do Not Open This Crate, a Step 4 Cat in the Hat book, does this too. The sister gets grabbed by a big man at the book’s climax, and the brother saves her by hitting the man with a bat and grabbing her. The first time I read it I couldn’t help but just roll my eyes. I asked out loud why the girl has to be so helpless.

My son’s favorite writer for a while now has been Mo Willems. For the most part, I’m happy about that because his writing is funny. In Don’t Let The Pigeon Stay Up Late, though, the pigeon protests, “it’s the middle of the day in China!” I suppose the pigeon is not wrong, given that the book is published in America, but I wonder how many children might feel alienated by that line. This reference isn’t really funny, especially because of the history of distancing and Orientalizing Asian countries. Treating China as a far off land where people are awake at night is at least slightly misleading. I always mention that that line wouldn’t be true if we were reading this in China.

I don’t think these examples are meant to be cruel but rather that they are the beginnings of larger social cues that shape people’s minds over time. This is where these messages start. I also don’t want to take a book away from my child because it’s imperfect, but I do want to question outdated standards as I notice them in his life. The other day, I looked for him when things got a little too quiet in the other room. It turned out that he was sitting in the living room in a pile of books on the floor looking at one page in Norman Bridwell’s Clifford’s First Snow Day that has a black boy, who is the only black character in the book, almost running the dog over in ice skates. My son wouldn’t look away from him. I asked what he was thinking, but he didn’t really say anything. I have to wonder how these messages affect the way he thinks about himself, as a black boy, and those around him. Now, when we read that book I always stop at that page to say something like that boy doesn’t mean to scare Clifford–it’s an accident.

To balance out these types of problems, books like I Like Myself! By Karen Beaumont, Mama’s Nightingale by Edwidge Danticat, and One Love adapted by Cedella Marley are all a part of the reading rotation at my house too. I hope that engaging with uncomfortable moments and more accurate stories will keep his ears and eyes open to injustices everywhere.

In All By Myself by Mercer Mayer, one of the Litter Critter books, the narrator offers up a variety of things that he can do now that he’s bigger. The book has a cute message about independence, but certain parts are awkward. Midway through, he says, “I can help Dad trim a bush or ice a cake for Mom.” Just like the “boys and girls” phrase in Piper’s book, I’m left wondering why these jobs are so boringly gendered. Do Not Open This Crate, a Step 4 Cat in the Hat book, does this too. The sister gets grabbed by a big man at the book’s climax, and the brother saves her by hitting the man with a bat and grabbing her. The first time I read it I couldn’t help but just roll my eyes. I asked out loud why the girl has to be so helpless.

My son’s favorite writer for a while now has been Mo Willems. For the most part, I’m happy about that because his writing is funny. In Don’t Let The Pigeon Stay Up Late, though, the pigeon protests, “it’s the middle of the day in China!” I suppose the pigeon is not wrong, given that the book is published in America, but I wonder how many children might feel alienated by that line. This reference isn’t really funny, especially because of the history of distancing and Orientalizing Asian countries. Treating China as a far off land where people are awake at night is at least slightly misleading. I always mention that that line wouldn’t be true if we were reading this in China.

I don’t think these examples are meant to be cruel but rather that they are the beginnings of larger social cues that shape people’s minds over time. This is where these messages start. I also don’t want to take a book away from my child because it’s imperfect, but I do want to question outdated standards as I notice them in his life. The other day, I looked for him when things got a little too quiet in the other room. It turned out that he was sitting in the living room in a pile of books on the floor looking at one page in Norman Bridwell’s Clifford’s First Snow Day that has a black boy, who is the only black character in the book, almost running the dog over in ice skates. My son wouldn’t look away from him. I asked what he was thinking, but he didn’t really say anything. I have to wonder how these messages affect the way he thinks about himself, as a black boy, and those around him. Now, when we read that book I always stop at that page to say something like that boy doesn’t mean to scare Clifford–it’s an accident.

To balance out these types of problems, books like I Like Myself! By Karen Beaumont, Mama’s Nightingale by Edwidge Danticat, and One Love adapted by Cedella Marley are all a part of the reading rotation at my house too. I hope that engaging with uncomfortable moments and more accurate stories will keep his ears and eyes open to injustices everywhere.

In All By Myself by Mercer Mayer, one of the Litter Critter books, the narrator offers up a variety of things that he can do now that he’s bigger. The book has a cute message about independence, but certain parts are awkward. Midway through, he says, “I can help Dad trim a bush or ice a cake for Mom.” Just like the “boys and girls” phrase in Piper’s book, I’m left wondering why these jobs are so boringly gendered. Do Not Open This Crate, a Step 4 Cat in the Hat book, does this too. The sister gets grabbed by a big man at the book’s climax, and the brother saves her by hitting the man with a bat and grabbing her. The first time I read it I couldn’t help but just roll my eyes. I asked out loud why the girl has to be so helpless.

My son’s favorite writer for a while now has been Mo Willems. For the most part, I’m happy about that because his writing is funny. In Don’t Let The Pigeon Stay Up Late, though, the pigeon protests, “it’s the middle of the day in China!” I suppose the pigeon is not wrong, given that the book is published in America, but I wonder how many children might feel alienated by that line. This reference isn’t really funny, especially because of the history of distancing and Orientalizing Asian countries. Treating China as a far off land where people are awake at night is at least slightly misleading. I always mention that that line wouldn’t be true if we were reading this in China.

I don’t think these examples are meant to be cruel but rather that they are the beginnings of larger social cues that shape people’s minds over time. This is where these messages start. I also don’t want to take a book away from my child because it’s imperfect, but I do want to question outdated standards as I notice them in his life. The other day, I looked for him when things got a little too quiet in the other room. It turned out that he was sitting in the living room in a pile of books on the floor looking at one page in Norman Bridwell’s Clifford’s First Snow Day that has a black boy, who is the only black character in the book, almost running the dog over in ice skates. My son wouldn’t look away from him. I asked what he was thinking, but he didn’t really say anything. I have to wonder how these messages affect the way he thinks about himself, as a black boy, and those around him. Now, when we read that book I always stop at that page to say something like that boy doesn’t mean to scare Clifford–it’s an accident.

To balance out these types of problems, books like I Like Myself! By Karen Beaumont, Mama’s Nightingale by Edwidge Danticat, and One Love adapted by Cedella Marley are all a part of the reading rotation at my house too. I hope that engaging with uncomfortable moments and more accurate stories will keep his ears and eyes open to injustices everywhere.

In All By Myself by Mercer Mayer, one of the Litter Critter books, the narrator offers up a variety of things that he can do now that he’s bigger. The book has a cute message about independence, but certain parts are awkward. Midway through, he says, “I can help Dad trim a bush or ice a cake for Mom.” Just like the “boys and girls” phrase in Piper’s book, I’m left wondering why these jobs are so boringly gendered. Do Not Open This Crate, a Step 4 Cat in the Hat book, does this too. The sister gets grabbed by a big man at the book’s climax, and the brother saves her by hitting the man with a bat and grabbing her. The first time I read it I couldn’t help but just roll my eyes. I asked out loud why the girl has to be so helpless.

My son’s favorite writer for a while now has been Mo Willems. For the most part, I’m happy about that because his writing is funny. In Don’t Let The Pigeon Stay Up Late, though, the pigeon protests, “it’s the middle of the day in China!” I suppose the pigeon is not wrong, given that the book is published in America, but I wonder how many children might feel alienated by that line. This reference isn’t really funny, especially because of the history of distancing and Orientalizing Asian countries. Treating China as a far off land where people are awake at night is at least slightly misleading. I always mention that that line wouldn’t be true if we were reading this in China.

I don’t think these examples are meant to be cruel but rather that they are the beginnings of larger social cues that shape people’s minds over time. This is where these messages start. I also don’t want to take a book away from my child because it’s imperfect, but I do want to question outdated standards as I notice them in his life. The other day, I looked for him when things got a little too quiet in the other room. It turned out that he was sitting in the living room in a pile of books on the floor looking at one page in Norman Bridwell’s Clifford’s First Snow Day that has a black boy, who is the only black character in the book, almost running the dog over in ice skates. My son wouldn’t look away from him. I asked what he was thinking, but he didn’t really say anything. I have to wonder how these messages affect the way he thinks about himself, as a black boy, and those around him. Now, when we read that book I always stop at that page to say something like that boy doesn’t mean to scare Clifford–it’s an accident.

To balance out these types of problems, books like I Like Myself! By Karen Beaumont, Mama’s Nightingale by Edwidge Danticat, and One Love adapted by Cedella Marley are all a part of the reading rotation at my house too. I hope that engaging with uncomfortable moments and more accurate stories will keep his ears and eyes open to injustices everywhere.