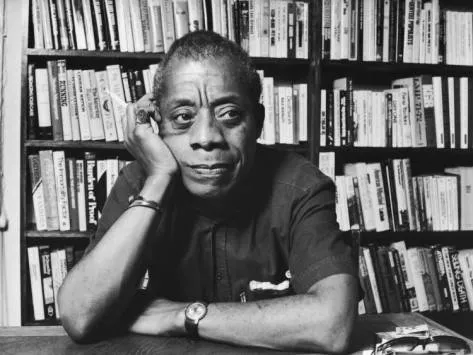

Reading Pathway: JAMES BALDWIN

James Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) wrote some of the most searing, unflinching, heartfelt, down-to-earth honest writing I’ve ever come across. And that includes fiction and nonfiction, both of which he mastered. Picking up a Baldwin is like jumping back in time: he’s writing amidst the race riots of Detroit and Harlem and the turmoil of the Civil Rights Movement, when ‘Negro’ was the preferred word still in use. But what shows through in his writing is the deep love and compassion that he learned through the struggles of his own existence, being poor, black, gay, and living in America. (For a quick, poetic recap of his life, click here.)

Even as he tells it like it is, Baldwin’s message is about love. Just about every sentence is poignantly quotable, and each book is a telling memoir – of people living in a hostile country, exploring sexuality, working through racial issues, learning to survive while trying to progress, coming to terms with the world as it was, while hoping that things get better. Whenever I read a Baldwin I can hear the voice of the author in every word and I want to tell him that yes, things are better, but there’s still lots to be done. Read on.

Referencing a biblical quote (“God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!”), this slim book is comprised of two essays, and one of them is absolutely essential Baldwin reading. His essay to his young namesake nephew, My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation, is Baldwin’s love letter to to a young man who is emerging into a world where he will be treated as less of a person, simply because of the color of his skin. And here is Baldwin’s advice: “You can only be destroyed by believing that you really are what the white world calls a nigger.” I tell you this because I love you, and please don’t you ever forget it.” It’s a short essay, it’s heartfelt, it’s memoir-ish, and it is beautiful. Please read it.

Giovanni’s Room. Straight, gay and American.

I wish James Baldwin were alive to see the world today. He was a prophet born before his time, and I wonder what he’d make of America, well past desegregation and with a revised civil rights movement, gay marriage recognized and legal in many U.S. states and several countries. Giovanni’s Room tells the story of David, a white American expatriate in 1950s Paris, who proposes to a woman, Hella, only to fall in love and have an affair with an Italian man, the titular Giovanni. Yep, that’s right. The story is told from David’s perspective, all in one night, as Giovanni awaits to be guillotined for the crime of murder. Baldwin’s second novel, the one publishers told him to burn rather than alienate his readers, is not afraid to discuss sexual identity and desires, what we want vs. the conventional life we’re supposed to lead, and the drama that surrounds even the simplest of relationships.

Giovanni’s Room is beautifully written, more restrained than his more fiery nonfiction essays, but complex and dramatic and bittersweet all at once. Even as it was published, the New York Times recognized the genius at work, writing that “Mr. Baldwin writes of these matters with an unusual degree of candor and yet with such dignity and intensity that he is saved from sensationalism.” David is a product of his time, when LGBTQ and “gay rights” were not yet born: Giovanni makes him happy, and yet the relationship is wrong, and the only way David can deal with his shame are through the usual avenues, drinking and violence. But even then, Baldwin reminds us of what really matters, in perhaps the novel’s most quoted line: “Somebody, your father or mine, should have told us that not many people have ever died of love. But multitudes have perished, and are perishing every hour – and in the oddest places! – for the lack of it.”

Notes of a Native Son. The best of the nonfiction.

Upon his return to America from self-imposed exile in Europe, Baldwin’s friend suggested he compile his essays into one book. “My reaction,” Baldwin notes in the book’s preface, “was not enthusiastic: as I remember, I told him that I was too young to publish my memoirs.” At thirty, Baldwin had already written several highly proclaimed novels, was pals with Marlon Brando, and his play was being produced at Howard university. But he still faced disdain from the publishing world, who told to Baldwin that publishing his open, honest novels would “would alienate his audience and ruin his career.” Baldwin persevered and got his books published, along with the compilation of essays, together inspired by “the conundrum of color..the inheritance of every American…a fearful inheritance, for which untold multitudes, long ago, sold their birthright.” Writing is Baldwin’s birthright, and he claims it in his essays.

The book is divided into thirds. The first section are commentaries on literature and the current pop culture reviews, such as you might read in the New York Times or on this very site. Baldwin dissects Uncle Tom’s Cabin with essay Everybody’s Protest Novel; get to the heart of the problem of Bigger Thomas from Native Son (“the most powerful and celebrated statement we have yet of what it means to be a Negro in America”) in Many Thousands Gone; and begins the conversation on what will become Blaxploitation through Carmen Jones: The Dark is Light Enough.

Section two is about juxtaposition. North vs. South: slavery-free The Harlem Ghetto, where Baldwin was born, and where he has seen change come, but not necessarily in a good way. This is an excellent self-critique of black media, politicians and leaders. In Journey to Atlanta Baldwin revisits a hotbed of slavery, where his brother returned and felt the discontent of the people still there and their distrust of anyone, including and possibly especially black, from the North. And finally family; in the aftermath of the 1943 Detroit race riots (“To smash something is the ghetto’s chronic need), Baldwin’s father dies; a few hours later his tiny baby brother is born; and on Baldwin’s birthday they bury his father. This final essay is Baldwin working through a lifetime of not understanding his father, but finally remembering, when it was too late to have the conversation, how his father loved Baldwin and raised him to be a good, respectful and spiritual man, in spite of the hate and hardship all around them. “When his life had ended,” Baldwin writes, “I began to wonder about that life and also, in a new way, to be apprehensive about my own.”

The final section deals with Baldwin and the escape to Europe to find his own identity, and the very real and very weird (for the 20th century) experience of finding himself as the first black person. As in – the first black person that a lot of Europeans, including the entire population of a Swiss mountain village, had ever seen, in real life. And of the American Negro coming into contact, alien-like, with Africans in Europe, which is a whole other thing. “They face each other, the Negro and the African, over a gulf of three hundred years – an alienation too vast to be conquered in an evening’s good-will, too heavy and too double-edged ever to be trapped in speech.”

Ok-I realized as I compiled this list that my favorites are Baldwin’s early works, and there are so many more to chose from. What are your favorites? [Ed note: For more guides to reading your way into amazing authors you’ve always wanted to try, check out Book Riot’s own books, START HERE and START HERE, Vol 2, available for $2.99 at your ebook retailer of choice.] _________________________ Sign up for our newsletter to have the best of Book Riot delivered straight to your inbox every week. No spam. We promise. To keep up with Book Riot on a daily basis, follow us on Twitter, like us on Facebook, , and subscribe to the Book Riot podcast in iTunes or via RSS. So much bookish goodness–all day, every day.