On “Slut Shelves” and Eating Our Own In Fiction

Slut: a woman who has many sexual encounters.

Slut: a word that has grown exponentially in use over the last few decades.

Slut: a word we toss around to condemn females who dare have power over their own bodily choices and experiences. A word we use when a woman’s right to her own body scares us. When it makes us uncomfortable. When it doesn’t work for us — when we feel our ways have been violated despite her choices having nothing to do with us.

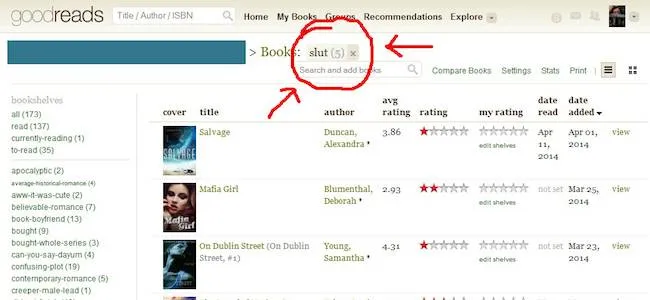

Last week, debut YA author Alexandra Duncan talked about stumbling across a shelf on Goodreads where her book Salvage was placed. This reader placed it under the label “slut,” along with a handful of other YA titles. Duncan goes on to unpack why finding her book on that shelf was hurtful, and it’s not because of what it says about her character. It’s what it says about her and other women who dare make choices about their own sexuality.

Rather than condemn this particular reviewer — which Duncan does a good job of not doing — she instead talks about how this sort of label is pervasive among women, used as a means of wielding control of other women. She writes:

And the worst part is, women buy into this. We do it to each other. We’ve all been dismissed for wearing the wrong thing or dating the wrong person or putting on too much makeup or simply making mistakes in our lives. Every woman has been slutshelved at some point. We should understand how hurtful these things are, yet we call each other nasty things like slut and whore. We judge each other harshly for what we wear and whether or not we conform to another person’s idea of what a woman really should be.Author Carrie Mesrobian wrote a series of tweets in response to Duncan’s original post, spun in light of how the main character in her book, Sex & Violence, doesn’t receive the same sort of shaming from readers, despite the fact he’s a irrepressibly horny teen boy: https://twitter.com/CarrieMesrobian/status/459406016602308610 https://twitter.com/CarrieMesrobian/status/459406284287000577 https://twitter.com/CarrieMesrobian/status/459406940406169600 https://twitter.com/CarrieMesrobian/status/459407159092998144 Evan isn’t condemned by readers for his sexual choices. He’s a player, and he’s unabashed about the way he seeks out girls and then sleeps with them. Mesrobian does not shy away from depicting Evan as a player. It’s part and parcel of who he is. Ava, though, who had sex one time in Duncan’s book, is a slut. Callie, the main character in Trish Doller’s Where the Stars Still Shine, another title on this Goodreads slut shelf, has just come out of a sexually abusive household, and when she finds a guy — just one — whom she finds herself sexually attracted to, she pursues and engages in those desires. It’s the first time she’s felt like her body belongs to her and not the hands of any number of older men abusing her, and she is ready to allow herself control of her own sexuality. What’s problematic here isn’t this shelf in particular, nor is it the shelves of any of a number of other Goodreads users who perpetuate the idea that girls who like sex in their books are sluts and therefore lack value. It’s not the reviews of books that are left on Amazon or blogs or anywhere else that equate a female character’s worth with her sexual appetite. Those are instead symptoms of a much more pervasive problem of sexism and reading altogether. Most of us grow up in a system where the educational curriculum is regimented and regulated, and it’s a curriculum where the prime reading material comes from white men. These are stories that set out to be thematic, to give us insight into life, to give us answers to what the meaning of everything is. But these are also stories that are deeply flawed in how they portray female characters — look at The Scarlet Letter or The Great Gatsby. These and many others are stories where men step in to become the heroes for female characters who are rendered helpless or problematic without the guidance of those burly dudes who know What’s Right And Proper. When we see women in our required reading, it’s often because it’s of niche or local interest, or because they’re writing in the margins or on the periphery of areas that fit into the curriculum or fulfill a core requirement. We have Emily Dickinson writing poetry, and we have our Austen and Brontes, who are writing Love Stories (and note, of course, many of the women we read had to hide their feminine identity, too, like George Eliot or Anne Bronte, who went by Acton Bell, and that those are the important facts we know about those writers when we end our units on them). These books are products of their times, of course. But in a recent survey educator Sarah Andersen conducted with her high school girls, she found teen girls aren’t seeing themselves and aren’t connecting with the books that they’re reading in school. Because there’s a lack of exposure to a wider range of female voices within education, there’s a missed opportunity for girls and boys to be exposed to the idea that female characters — that females — are allowed autonomy in the choices they make. That how they’re rendered in fiction, and the way we expose readers to them isn’t the standard operating model for how all females should be and act. As Andersen’s students pointed out, they’re eager for a wide range of female characters: they want romantics as much as they want strong and powerful girls. They want quiet and shy girls as much as they want loud and out-there girls. They want to see a wide representation of girls and what it means to look like and act like one because they themselves are a wide range of girls hoping to find some kind of validation for how they choose to act and behave and think and be. Women’s voices in fiction are drowned out and forgotten. What it means to be a girl is made into a myth — the myth that girls are meant to be easy to digest and the myth that the right girls are “not like other girls.” We label books for young readers as being books for boys or books for girls, and we perpetuate the idea that one gender is far more important to cater to than the other. That the voices and needs as females don’t matter as much because “what about the boys?” We call books where girls dare to make choices about their own bodily pleasure smut, and we treat them as lesser, and we call books where girls have their bodies taken advantage of the same damn thing. I think it’s pretty safe to say the boys in fiction and the boys who are reading it are doing just fine. I think it’s time that we wake the hell up and pay more attention to what it is we’re feeding our girls instead. Who are the characters they’re being exposed to? What are the discussions that they’re having about these female characters? What are the conversations we’re choosing to have with our girls about these characters? Because we can’t blame the books for the problem. We can only blame ourselves for the fact that there are still readers who believe there’s a necessity for things like a slut shelf or that people like me or Alexandra Duncan or any other female out there who has sex before marriage because she chooses to are worth less than any other human being. Every person comes into feminism differently, but to get there, those of us who are advocates for books and advocates for readers need to do better in opening up important — and sometimes scary — channels of dialog. In that exposure and in that vulnerability, we show people that feminist isn’t a slur. Feminism: a belief that all people — men and women and those who identify otherwise — who make choices deserve equal rights to make those choices for themselves. Feminist: a person who supports feminism and/or relating to an idea that supports feminism. Feminism and Feminist: two words declining in use. It’s time we all build some slut shelves in our libraries, classrooms, and in our homes. But more than simply building them, let’s open up some dialog about what these terms and labels mean — and the whys behind them.