Erasure Poetry, HEART OF DARKNESS, and the Language of Conflict

In recent years, I’ve been a steady listener to the Poetry Off the Shelf podcast produced by the Poetry Foundation. These podcasts last about ten minutes and are released about three times a month. One of my favorites is “The Poetry of Erasure,” from January 1, 2010. Narrated by poet Sarah Campbell and including an interview with poet and critic Ron Silliman, “The Poetry of Erasure” provides a quick history of erasure poetry, a technique that re-visions existing texts (literary, political, media-related, etc.) by omitting (erasing) phrases and/or whole passages and presenting only the words that remain.

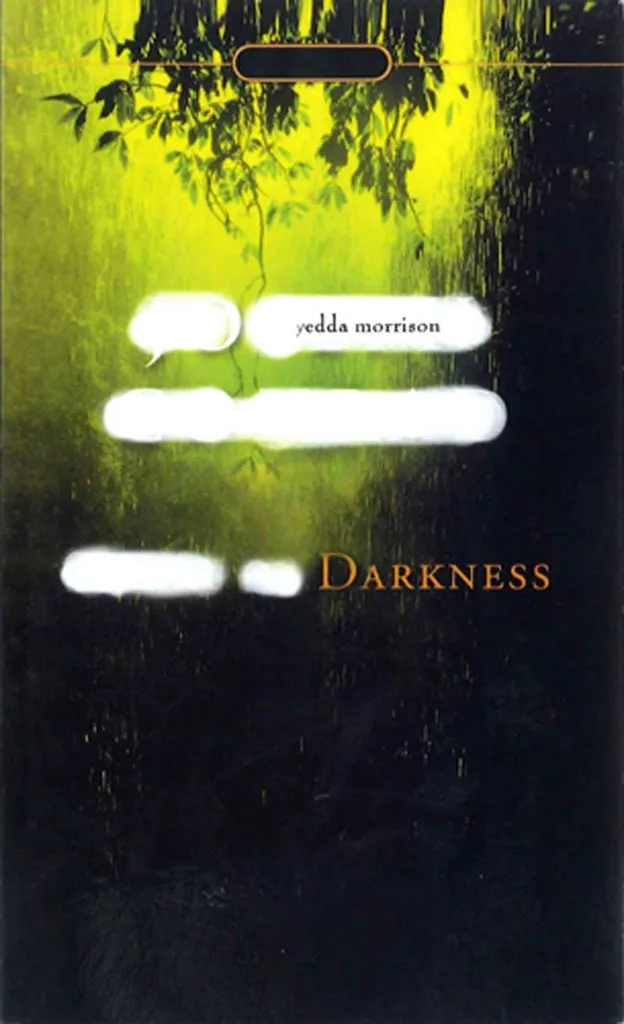

The podcast highlights the work of Yedda Morrison, a poet and visual artist, who took Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and whited out every word not referring to nature. In the resulting poem, “Darkness,” Morrison left the remaining words on the page as originally presented in Conrad’s novella, adding a visual component to the reading experience. In the podcast, Morrison says the process turned Heart of Darkness into a kind of word picture in which the volume of everything human was muted, overshadowed by the presence of the natural world. Both the first chapter of “Darkness” and the podcast provide a good intro to the form–the pod overlays a reading of the original novella with a recording of Morrison reading her erased version (along with a nice bonus: audio from Apocalypse Now, Coppola’s 1979 movie adaptation of Heart of Darkness).

Erasure poetry’s been on my mind for a couple reasons. I keep hearing it at poetry readings here in New York; I’ve been thinking about the inherent poetic emphasis on compression in connection with my own writing; and erasure seems like compression of compression. In the podcast, Campbell says that the empty spaces left on the page in “Darkness” feel especially suggestive and meaningful. For me, one effect of these blank spaces is to immerse readers in the immensity and mystery of the natural world.

Who knows how the mind works? But over the weekend, I found myself circling words and phrases in a New York Times article about the French intervention in Mali. I continue to be more than a little baffled by the language of war and the challenge of describing Western armies engaged in some of the world’s less developed spaces. As evidenced by the pending parentheticals (wait for them), the socio-cultural (there must be a more meaningful adjective, but this is BIG, so) socio-cultural contrasts in the on-the-ground reality (e.g., sub-Saharan Africa, the Sahel, Malian desert) of Western resources (wow, that’s a euphemism) and militant Islamists (something goes here but after more than a decade of reading and thinking about these groups I still don’t have a readymade understanding of who they are exactly) in far-flung, remote locales (though not so far-flung or remote to the people who live there) might be better communicated in a quick erasure poem culled from the NYT article (as compared to a lengthy analytical prose piece):

Under the control of the Movement for Oneness

Timbuktu fabled desert oasis fell

when 300 pickup trucks of fighters rolled in

French bombs and rebel bullets ricocheting

around mud-walled dwellings a nomadic people

took down the Malian flag and raised

a white piece of paper printed with words in Arabic—

“Assembly for the Spiritual Ideology to Purify the African World”—

and pictures of machine guns