Size Matters: On the Lost Art of Brevity

A good story is a good story no matter what the length. However, there is a trend these days that implies the bigger the better. Unless you’re trying to win a Hugo Award where a minimum of 40,000 words is a requirement, length does not actually matter to a story (although events like NaNoWriMo with its 50,000-word arbitrary goal and the books regularly getting movie deals these days would have us believe otherwise).

Brevity is a lost art.

- Harry Potter : 7 books/4,095 pages with a 585 page average; shortest at 309 pages and longest at 870

- A Song of Fire and Ice: 5 books, 2 more on the way/2,562 pages; the 854 page average skewed thanks to the 1056 page A Dance With Dragons

It’s not like books have never been atrociously long before – Les Miserables clocks in at 1042 pages. J.R.R. Tolkien is the king of multi-volume story with Lord of the Rings, which is 1728 pages if you include The Hobbit (more with the addition of appendices and supplementary books). Charles Dickens’ longest book is Bleak House if you go by page number (928), David Copperfield if you go by word count (358,000).

The difference between these lengthy tomes and our modern ones is that when they were written (with the exception of Tolkien), these books were everything – they were the radio, television, and internet of their day – the perfect escape for the whole family to enjoy with the occasional “after the kids are in bed” reads like The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, Gentleman – it’s own length a joke, as Shandy is unable to stay on subject without several tangents to his own story. Even so, the book is only 342 pages.

Then, like today, length could mean money. Dickens certainly mastered the art of stringing the plot along for the sake of a serial, supposedly paid by the word. But length was also a product of simply having time on one’s hands; Fanny Burney’s Evelina might not have been 600 pages long if she was writing in between a day job and picking up the kids from school.

Ultimately, a book should only be as long as it takes to tell the story – no longer, no shorter. George Orwell managed Animal Farm just fine in 168 pages, while Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men is only 108 pages. And while there is nothing wrong with a long novel if its length is what it takes to tell the story, just think of how much shorter Twilight (2,720 pages) could have been if an editor had told Meyer to stop with all the amber eyes/ice cold skin repetition. The story would still have had problems, but each book would have been about 50 pages shorter (yes, hyperbole). Even The Neverending Story manages to be 2,336 pages shorter than Twilight.

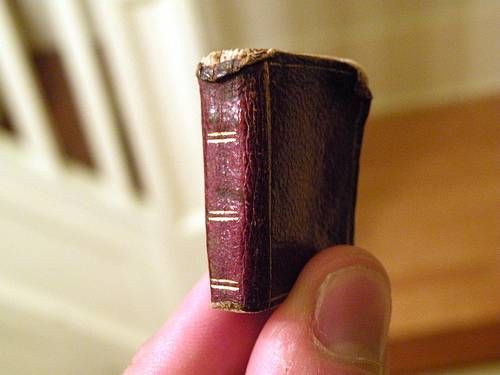

There’s something wonderful about a novel where the weight is in the words, not page count. Shakespeare stated that “brevity is the soul of wit,” but it is also the soul of a book where each word means something.

Recently, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s HitRecord.org released the second volume of Tiny Stories, described by the LA Times as having “haiku-like precision.” These pocket-sized books are preceded by the ultimate big meaning in tiny packaging story. Ernest Hemingway is said to have written the shortest story as part of a barroom challenge on a cocktail napkin:

For sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.

Hemingway nailed the brevity with this story – it says more precisely because it says less.