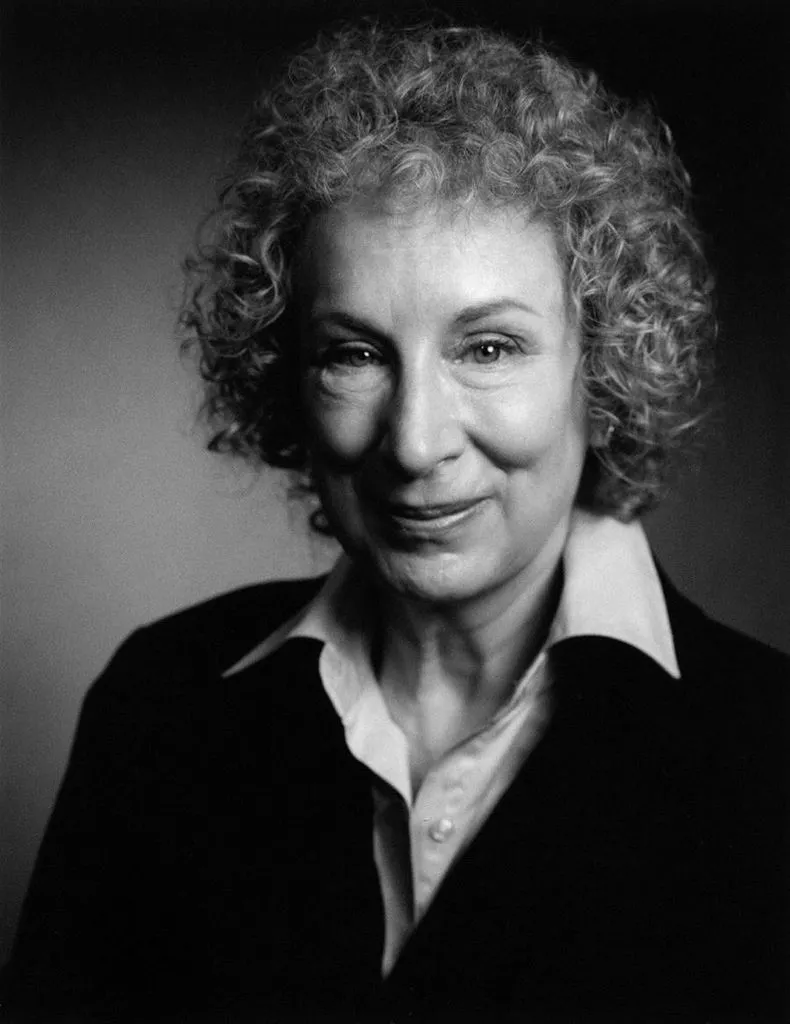

Reading Pathways: Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood. Maggie. Companion of the Order of Canada. Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. Bad-ass bitch of Canadian letters. Margaret Atwood.

I have been finger-tied putting together this Reading Pathway about Margaret Atwood, because from my position as a (a) Canadian (b) feminist (c) academic working in (d) Canadian Literature, Maggie is my personal lord and saviour. The right answer to “what should I read by Margaret Atwood?” is EVERYTHING. RIGHT NOW. DO IT. I recognize that this is not at all helpful, but it has kept me all confused about how to approach the task of recommending a way into the enormous and diverse Atwood oeuvre.

Because that’s the thing: it’s maddeningly diverse. There’s speculative fiction and historical fiction, there’s poetry and non-fiction prose, there’s treatise on the history of Canadian Literature and some of the most exquisite fiction you will ever encounter. 13 novels, 9 short story collections, 20 poetry collections, and 10 works of non-fiction. And it’s pretty much all awesome. So where do we start?

Amazingly, this is the one thing I think my high school English curriculum actually got right. If you went to high school in Canada in the 1990s, it’s likely that your introduction to Margaret Atwood came from The Handmaid’s Tale in grade 10 or 11, and the more I have thought about ways into Atwood the more that makes sense as an entry point. So it’s where I’m starting today, too.

1. The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). We’re starting with this dystopic novel about a world where women’s rights have been suppressed because it introduces you to the two major themes of Atwood’s writing: gender power relations and speculative / social science fiction. If you like The Handmaid’s Tale, you’ll find something to like in everything else in Atwood’s oeuvre. This novel also prepares you for things you will continue to encounter throughout the rest this pathway: challenging narrators who mask and obfuscate, unconventional endings, and really disturbing gender politics. Which takes us to…

1. The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). We’re starting with this dystopic novel about a world where women’s rights have been suppressed because it introduces you to the two major themes of Atwood’s writing: gender power relations and speculative / social science fiction. If you like The Handmaid’s Tale, you’ll find something to like in everything else in Atwood’s oeuvre. This novel also prepares you for things you will continue to encounter throughout the rest this pathway: challenging narrators who mask and obfuscate, unconventional endings, and really disturbing gender politics. Which takes us to…

2. Power Politics (1971). This is for LitFic people who want a way into Atwood: You gotta read some poetry. I know, some people are pretty poetry averse, and I get that (see what I did there? a-verse?), but to understand the way Atwood uses imagery and the way she shapes language, you need to see how she works as a poet. Like so many of the greatest writers of her generation in Canada, her prose is deeply influenced by her background as a poet. And, I mean, we’re talking about the poetry collection that includes this:

2. Power Politics (1971). This is for LitFic people who want a way into Atwood: You gotta read some poetry. I know, some people are pretty poetry averse, and I get that (see what I did there? a-verse?), but to understand the way Atwood uses imagery and the way she shapes language, you need to see how she works as a poet. Like so many of the greatest writers of her generation in Canada, her prose is deeply influenced by her background as a poet. And, I mean, we’re talking about the poetry collection that includes this:

3. Alias Grace (1996). It would be a controversial call to assert that the end point in reading Atwood is Alias Grace, as The Blind Assassin (2000) was more lauded and a Booker Prize winner, and Oryx and Crake (2003) has been so staggeringly popular. Indeed, I’m not saying this is the end of your Atwood reading. But I think Alias Grace sets you up for everything that you could approach after. You’re primed after The Handmaid’s Tale and Power Politics for the depth of discussion about gender here; Alias Grace sets you up for the rest of Atwood’s work because it is a historical narrative with a compelling central mystery and a not-so-reliable narrator. These are tropes you will encounter again. But Alias Grace is also beautiful, affecting prose, wrenching tears and gasps from you in that typically Atwoodian way that suggests black humour is never far behind.

I suspect this is an unconventional approach to Atwood, but I think it sets readers up for the best of her genre-bendingly diverse body of work. I think any reader who works through these three texts can approach any other Atwood text with confidence. But I know I’m not the only Atwood fan — what say you, Rioters? Have I got it right or missed the mark? Let me know in the comments.

3. Alias Grace (1996). It would be a controversial call to assert that the end point in reading Atwood is Alias Grace, as The Blind Assassin (2000) was more lauded and a Booker Prize winner, and Oryx and Crake (2003) has been so staggeringly popular. Indeed, I’m not saying this is the end of your Atwood reading. But I think Alias Grace sets you up for everything that you could approach after. You’re primed after The Handmaid’s Tale and Power Politics for the depth of discussion about gender here; Alias Grace sets you up for the rest of Atwood’s work because it is a historical narrative with a compelling central mystery and a not-so-reliable narrator. These are tropes you will encounter again. But Alias Grace is also beautiful, affecting prose, wrenching tears and gasps from you in that typically Atwoodian way that suggests black humour is never far behind.

I suspect this is an unconventional approach to Atwood, but I think it sets readers up for the best of her genre-bendingly diverse body of work. I think any reader who works through these three texts can approach any other Atwood text with confidence. But I know I’m not the only Atwood fan — what say you, Rioters? Have I got it right or missed the mark? Let me know in the comments.

1. The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). We’re starting with this dystopic novel about a world where women’s rights have been suppressed because it introduces you to the two major themes of Atwood’s writing: gender power relations and speculative / social science fiction. If you like The Handmaid’s Tale, you’ll find something to like in everything else in Atwood’s oeuvre. This novel also prepares you for things you will continue to encounter throughout the rest this pathway: challenging narrators who mask and obfuscate, unconventional endings, and really disturbing gender politics. Which takes us to…

1. The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). We’re starting with this dystopic novel about a world where women’s rights have been suppressed because it introduces you to the two major themes of Atwood’s writing: gender power relations and speculative / social science fiction. If you like The Handmaid’s Tale, you’ll find something to like in everything else in Atwood’s oeuvre. This novel also prepares you for things you will continue to encounter throughout the rest this pathway: challenging narrators who mask and obfuscate, unconventional endings, and really disturbing gender politics. Which takes us to…

2. Power Politics (1971). This is for LitFic people who want a way into Atwood: You gotta read some poetry. I know, some people are pretty poetry averse, and I get that (see what I did there? a-verse?), but to understand the way Atwood uses imagery and the way she shapes language, you need to see how she works as a poet. Like so many of the greatest writers of her generation in Canada, her prose is deeply influenced by her background as a poet. And, I mean, we’re talking about the poetry collection that includes this:

2. Power Politics (1971). This is for LitFic people who want a way into Atwood: You gotta read some poetry. I know, some people are pretty poetry averse, and I get that (see what I did there? a-verse?), but to understand the way Atwood uses imagery and the way she shapes language, you need to see how she works as a poet. Like so many of the greatest writers of her generation in Canada, her prose is deeply influenced by her background as a poet. And, I mean, we’re talking about the poetry collection that includes this:

you fit into me like a hook into an eye a fish hook an open eyeI mean, come on. That is amazing. And those surprisingly violent images are characteristic of Atwood’s prose as much as of her poetry, but in her poetry they are clearer and stronger.

3. Alias Grace (1996). It would be a controversial call to assert that the end point in reading Atwood is Alias Grace, as The Blind Assassin (2000) was more lauded and a Booker Prize winner, and Oryx and Crake (2003) has been so staggeringly popular. Indeed, I’m not saying this is the end of your Atwood reading. But I think Alias Grace sets you up for everything that you could approach after. You’re primed after The Handmaid’s Tale and Power Politics for the depth of discussion about gender here; Alias Grace sets you up for the rest of Atwood’s work because it is a historical narrative with a compelling central mystery and a not-so-reliable narrator. These are tropes you will encounter again. But Alias Grace is also beautiful, affecting prose, wrenching tears and gasps from you in that typically Atwoodian way that suggests black humour is never far behind.

I suspect this is an unconventional approach to Atwood, but I think it sets readers up for the best of her genre-bendingly diverse body of work. I think any reader who works through these three texts can approach any other Atwood text with confidence. But I know I’m not the only Atwood fan — what say you, Rioters? Have I got it right or missed the mark? Let me know in the comments.

3. Alias Grace (1996). It would be a controversial call to assert that the end point in reading Atwood is Alias Grace, as The Blind Assassin (2000) was more lauded and a Booker Prize winner, and Oryx and Crake (2003) has been so staggeringly popular. Indeed, I’m not saying this is the end of your Atwood reading. But I think Alias Grace sets you up for everything that you could approach after. You’re primed after The Handmaid’s Tale and Power Politics for the depth of discussion about gender here; Alias Grace sets you up for the rest of Atwood’s work because it is a historical narrative with a compelling central mystery and a not-so-reliable narrator. These are tropes you will encounter again. But Alias Grace is also beautiful, affecting prose, wrenching tears and gasps from you in that typically Atwoodian way that suggests black humour is never far behind.

I suspect this is an unconventional approach to Atwood, but I think it sets readers up for the best of her genre-bendingly diverse body of work. I think any reader who works through these three texts can approach any other Atwood text with confidence. But I know I’m not the only Atwood fan — what say you, Rioters? Have I got it right or missed the mark? Let me know in the comments.