Writing and Addiction in Stephen King’s MISERY

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I read Stephen King’s Misery for the first time this year. It was during the Popular Culture Association conference in April, and I was stuck in bed in my hotel room (which was charmingly located above the entrance to the parking garage) down for the count with the conference crud. Armed with orange juice, tissues, and a veritable armory of cold meds, I devoured King’s 1987 novel about obsession, madness, and the horrors of writing.

The thing that struck me most about Misery was that the book was as much about writing and the writing process as it was about the horror of Paul’s predicament. If not more so. Don’t get me wrong, Misery is terrifying. I flinched, I cringed, I tried to read while simultaneously not looking at the page (which doesn’t work very well). But through all the dismemberment and my (somewhat morbidly delighted) disgust, I started to realize that there was something else going on between the lines in Misery with regards to Paul and his work.

Of course what I was seeing could have just been the cold meds.

So once I was home again, and well again, I made sure to sit down and reread Misery, paying careful attention to what the novel had to say about writing.

The thing that struck me most about Misery was that the book was as much about writing and the writing process as it was about the horror of Paul’s predicament. If not more so. Don’t get me wrong, Misery is terrifying. I flinched, I cringed, I tried to read while simultaneously not looking at the page (which doesn’t work very well). But through all the dismemberment and my (somewhat morbidly delighted) disgust, I started to realize that there was something else going on between the lines in Misery with regards to Paul and his work.

Of course what I was seeing could have just been the cold meds.

So once I was home again, and well again, I made sure to sit down and reread Misery, paying careful attention to what the novel had to say about writing.

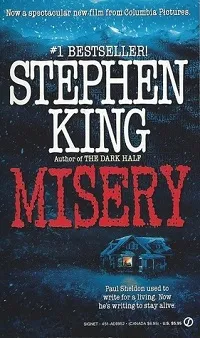

King, Stephen. Misery. Signet MMP Edition, 1988. King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. 10th Anniversary Edition, Scribner, 2010.

The thing that struck me most about Misery was that the book was as much about writing and the writing process as it was about the horror of Paul’s predicament. If not more so. Don’t get me wrong, Misery is terrifying. I flinched, I cringed, I tried to read while simultaneously not looking at the page (which doesn’t work very well). But through all the dismemberment and my (somewhat morbidly delighted) disgust, I started to realize that there was something else going on between the lines in Misery with regards to Paul and his work.

Of course what I was seeing could have just been the cold meds.

So once I was home again, and well again, I made sure to sit down and reread Misery, paying careful attention to what the novel had to say about writing.

The thing that struck me most about Misery was that the book was as much about writing and the writing process as it was about the horror of Paul’s predicament. If not more so. Don’t get me wrong, Misery is terrifying. I flinched, I cringed, I tried to read while simultaneously not looking at the page (which doesn’t work very well). But through all the dismemberment and my (somewhat morbidly delighted) disgust, I started to realize that there was something else going on between the lines in Misery with regards to Paul and his work.

Of course what I was seeing could have just been the cold meds.

So once I was home again, and well again, I made sure to sit down and reread Misery, paying careful attention to what the novel had to say about writing.

Writing and Addiction

Misery is a book about addiction, in both a textual and metatextual sense. It is a book in which addiction is explored in multiple forms by both characters, and it is also a book about the nature of addiction, written by a man familiar with the concept. King wrote Misery about cocaine addiction specifically: “Misery is a book about cocaine. Annie Wilkes is cocaine. She was my number-one fan” (The Rolling Stone, 2014). In his memoir On Writing, King wrote about the “part” in his brain that recognized the depth of his addiction and “began to scream for help in the the only way it knew how, through my fiction and through my monsters” (p. 96), and he references Misery, in particular, with its imprisoned and tortured writer. Misery begins with author Paul Sheldon celebrating having finished a new, “real” book. Though it was his Misery novels (a series of pulp historical adventure romances comparable to the Angélique novels by Anne and Serge Golon) that made Paul a bestseller, he is deeply ashamed of his work which he views as trashy. He resents the Misery novels because they have led the critics to label him a “‘popular author’ (which was, as he understood it, one step – a small one – above that of a ‘hack’)” (p. 286), which, though it takes until nearly the end of the novel for him acknowledge it, “hurt him quite badly” (p. 286) and shook his confidence as a writer. So even though at the beginning of Misery Paul has just finished this new, “serious” work, Fast Cars, and though he may think he is celebrating, the truth is that the two bottles of champagne he downs, and his impulsive decision to drive west like someone in making a new start, are coping mechanisms. These things are Paul’s attempt to convince himself that this new book is the “real book that will finally transform him into a “serious” author, despite his doubts to the contrary. The champagne is also a sign of a deeper problem: in the perceived absence of success, and amid his constant need for reassurance from his peers, Paul has begun to drink heavily to compensate. He refers to his excessive drinking multiple times throughout the book; to late nights, and late morning hangovers, downing Rolaids like candy. And the more he drinks, the more it interferes with his writing. It is a form of self-sabotage driven by his perpetual fear of not being good enough and never living up to his talent. Even before the car crash that puts him in Annie Wilkes’s hands and leads to his subsequent addiction to the painkiller Novril, Paul is already an addict; Annie is only substituting his drug of choice. And then she substitutes it a second time, by bringing him the typewriter. What I find entertaining is the fact that Annie first creates one addiction, meant to keep Paul tethered to her by a short leash, then provides him with a second addiction that gives him the means to escape her, without even realizing that is what she’s done. More than once in the novel it’s made explicit that Annie has no concept of, nor interest in, the process of writing. She’s what Paul call’s a “constant reader”; she doesn’t care about the “how,” she just wants the final product. And because she has no real understanding of writing, she doesn’t understand its power. The one time she sees Paul in a real frenzy of inspiration, she’s awed (p. 165). To Annie, who refers at one point to Paul’s “God-given talent” (p. 72), this act of creation is some sort of unknowable, divine thing. But she doesn’t realize that wherever the talent comes from, or doesn’t come from, what it provides Paul is a means to process the trauma to which she subjects him. Thus allowing him to make repairs to the psyche that Annie repeatedly damages throughout the book. There’s been quite a bit written on just “what” Annie is to Paul. She’s a metaphor for cocaine, we know, and certainly she torments Paul in her guise as Madame Addiction, both causing and soothing his pain. But what is she with regards to Paul and to his writing? In a way, Annie is like a sick sort of muse. A muse and an ego check all in one. She forces him to burn his Fast Cars manuscript by hand, the only copy, swearing up and down that it’s no good, putting a sizable dent in his already shaky writer’s confidence. Then she traps him in the figurative “writer’s chair” by putting him a wheelchair and placing a board across the arms, and forces him to go back to writing the Misery series that she loves and Paul so detests. Though Paul cannot, for his own safety, refuse Annie’s impossible demand that he write Misery back from the dead, we do see Paul’s attempt to resist the urge to write (and to return to Misery’s pulpy, melodramatic, but blissfully easy world) in his refusal at first to even look at the typewriter. But Paul can only sustain the attempt for so long before he finds himself unconsciously “looking at the typewriter again with avid repulsed fascination, not even aware of just when his gaze had shifted” (p. 64). He has no desire to write for Annie, but at the same time he cannot resist the desire to create. He watches the typewriter the same way he watched the clock in the first part of the novel, waiting for that next dose of Novril. There are a few quotes in particular that I think exemplify the novel’s perception and portrayal of writing as an addiction, aside from the aforementioned scene with the typewriter: The first quote, “There were days when he felt he could bend spoons simply by looking at them. Other days he felt like weeping hysterically” (p. 162), is self-explanatory. Were you to look in my reading journal, you would see the words “that’s writing for you” scrawled underneath this quote, and I think most writers would agree. Even if you are a steady writer, who sits down to work everyday and puts words on a page, there are still days when it’s like picking flowers and days when it’s like pulling carrots. I’ve seen this quote used as an example of the ways in which Paul’s writing parallels the cyclical nature of Annie’s bipolar (Carol A. Senf, “Stephen King’s Misery: Manic Depression and Creativity”, Dionysus in Literature: Essays on Literary Madness), but it could also be said to parallel the highs and subsequent lows of addiction, and I’m instantly reminded of Paul’s memory (and eventual hallucination) of the half-buried pilings on the beach that appear and vanish with the tide (and with the Novril) (p. 4). The next quote relates to a facet of writing that Paul calls “The Gotta” (p. 257). In short, the gotta is that impulse shared by writers and readers that makes them insist that they “have to know.” They’ve gotta know. They’ve gotta get to the end, see it through, see how it all shakes out. Even if it means staying up reading until 2:00 in the morning, or churning out words and pages at a breakneck pace into the wee hours of the day. A writer would know when they found the gotta because that was the moment the “hole in the paper” (how Paul refers to his ability to see the story playing out in his head) “widened to VistaVision width and the light shone through like a sunray in a Cecil B. DeMille epic” (p. 243). The Gotta: A craving, a compulsion, an undeniable need for more. The third quote pertains to Paul’s thoughts about finishing the book as he nears the end of Misery’s Return: “Working on it was torture, and finishing was going to mean the end of his life” (p. 257). I love this line, because in any other context it would be a hyperbolic, figurative rumination on the nature of writing and finishing a book. There is a passage from earlier in Misery, when Annie is trying to force Paul to burn the manuscript of Fast Cars, and he remembers the day he started the book, “walking around the apartment from room to room, big with book, more than big, gravid, and here [referring to the manuscript] were the labor pains”. He recalls the “blessed relief of starting” (p. 46). This perception of starting a book as a kind of childbirth would seem to underscore the figurative sense above of finishing something difficult that culminates in a life transition (though in this case the “end” of life is also figurative, referring only to the transition to parenthood). It could also be considered, per the subject of this discussion, a figurative statement about the nature of addiction: being addicted is torturous, but getting clean is harder, potentially even deadly. Finishing a book can feel as much like a death as a birth. But what I love, what makes me laugh, is that this line that, again, in any other context would be figurative, is in fact a literal statement. Working on Misery’s Return has been actual, physical torture for Paul, and finishing the book will in fact result in his death. Okay, so it’s a dark humor. Don’t judge. Most writers will recognize themselves and/or their craft in at least one of the excerpts above. It’s true that writing is an addiction in its own way, though one of the better addictions to have. It comes with its own beautiful highs and terrible lows, and though its results are often creative, rather than destructive, no one who writes is left unchanged by years of “use.” This brief essay touches on only one of the many ways in which Misery discusses writing, and is itself only half-formed, with ideas still to be expanded, explored, and complicated. I have not fully discussed the use of writing in the novel as a means of confronting trauma, a facet of Misery’s composition which King confirms was intentional in On Writing, when he discusses Paul’s efforts to “play Scheherazade,” giving King the “chance to say some things about the redemptive power of writing that [he] had long felt but never articulated” (p. 168). Nor have I more than briefly mentioned Paul’s conflicted sense of self with regards to the writer he is versus the writer he thinks he should be, and how that conflict complicates his feelings for the Misery novels. Stephen King’s Misery is a dense novel, full of overlapping layers and meanings, some of which even conflict. I could read it again tomorrow and discover something I missed the last two times. And that, in and of itself, is an extension of the discussion being had within the book about “pulp” versus “real” fiction, and who gets to say which books have value as “serious” literature.King, Stephen. Misery. Signet MMP Edition, 1988. King, Stephen. On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. 10th Anniversary Edition, Scribner, 2010.