Why Modernizing Nancy Drew Doesn’t Work

I recently watched the 2007 Nancy Drew movie, entirely on a whim, and I have feelings about it. Reader, they are not good feelings.

(I will preface this by saying that Emma Roberts, who played Nancy, was delightful, as was the entire cast. They were not the problem.)

To save you time, I will summarize the movie: set in modern times, Nancy heads west to Los Angeles (side note, I have always thought River Heights was in California and have just learned that I was wrong) when her father Carson Drew takes a temporary job. He makes her promise to stop taking cases and focus on high school, which she does…but she can’t help herself, and arranges for them to live in the former home of a movie star who lived and died under mysterious circumstances. Nancy, while balancing school life complete with mean girls and a 12-year-old suitor (whut?), discovers that the movie star may have left an altered last will and testament…and a secret love child! GASP! Of course, Nancy breaks her promise and gets in deep, finding the love child (now a grownup woman played by Rachael Leigh Cook, whom I adore) and putting herself in grave danger!

It’s not a terrible plot, though it isn’t good, but the real problem is that Nancy is not Nancy. The movie uses her name and the basic concept of a teenager who solves all of the mysteries that keep falling into her lap, and tries to make another Veronica Mars (I guess) while ignoring everything that made Nancy stand out. They inexplicably give her a love of everything vintage and retro, dressing her in sweater sets for no reason. She is a little dorky and somewhat clueless, which is the opposite of the self-assured, confident Nancy of the books.

There is one scene in particular that exemplifies the total lack of understand the filmmakers had of the character: Nancy is driving, in pursuit of some bad guy henchmen, and loses them because she refuses to go above the speed limit. Nancy. Drew. Refuses. To. Chase. Henchmen.

(I will preface this by saying that Emma Roberts, who played Nancy, was delightful, as was the entire cast. They were not the problem.)

To save you time, I will summarize the movie: set in modern times, Nancy heads west to Los Angeles (side note, I have always thought River Heights was in California and have just learned that I was wrong) when her father Carson Drew takes a temporary job. He makes her promise to stop taking cases and focus on high school, which she does…but she can’t help herself, and arranges for them to live in the former home of a movie star who lived and died under mysterious circumstances. Nancy, while balancing school life complete with mean girls and a 12-year-old suitor (whut?), discovers that the movie star may have left an altered last will and testament…and a secret love child! GASP! Of course, Nancy breaks her promise and gets in deep, finding the love child (now a grownup woman played by Rachael Leigh Cook, whom I adore) and putting herself in grave danger!

It’s not a terrible plot, though it isn’t good, but the real problem is that Nancy is not Nancy. The movie uses her name and the basic concept of a teenager who solves all of the mysteries that keep falling into her lap, and tries to make another Veronica Mars (I guess) while ignoring everything that made Nancy stand out. They inexplicably give her a love of everything vintage and retro, dressing her in sweater sets for no reason. She is a little dorky and somewhat clueless, which is the opposite of the self-assured, confident Nancy of the books.

There is one scene in particular that exemplifies the total lack of understand the filmmakers had of the character: Nancy is driving, in pursuit of some bad guy henchmen, and loses them because she refuses to go above the speed limit. Nancy. Drew. Refuses. To. Chase. Henchmen.

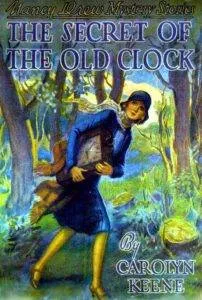

Nancy Drew was a fashion-forward genius, finished with high school, with a father who fully supported her sleuthing. She was law-abiding, but would absolutely push that boundary to help someone, which is what all of her cases boiled down to. The ‘real’ Nancy wouldn’t let the bad guys get away by being so doggedly good. (I am fairly certain there were no speed limits in the 1930s, so an updated Nancy story needs to consider her responses to other breakable laws in the books and base its characterization on those. Nancy committed so many instances of breaking and entering, trespassing, etc., that I can’t see how having her refuse to speed is consistent characterization.)

Maybe Nancy as she was written is too dull for a modernization, though I don’t really see how. Perhaps the problem is with the men who are writing her now, and lack the imagination to meet the standards of the women whose words formed her story in the first place.

Nancy Drew was a fashion-forward genius, finished with high school, with a father who fully supported her sleuthing. She was law-abiding, but would absolutely push that boundary to help someone, which is what all of her cases boiled down to. The ‘real’ Nancy wouldn’t let the bad guys get away by being so doggedly good. (I am fairly certain there were no speed limits in the 1930s, so an updated Nancy story needs to consider her responses to other breakable laws in the books and base its characterization on those. Nancy committed so many instances of breaking and entering, trespassing, etc., that I can’t see how having her refuse to speed is consistent characterization.)

Maybe Nancy as she was written is too dull for a modernization, though I don’t really see how. Perhaps the problem is with the men who are writing her now, and lack the imagination to meet the standards of the women whose words formed her story in the first place.

(I will preface this by saying that Emma Roberts, who played Nancy, was delightful, as was the entire cast. They were not the problem.)

To save you time, I will summarize the movie: set in modern times, Nancy heads west to Los Angeles (side note, I have always thought River Heights was in California and have just learned that I was wrong) when her father Carson Drew takes a temporary job. He makes her promise to stop taking cases and focus on high school, which she does…but she can’t help herself, and arranges for them to live in the former home of a movie star who lived and died under mysterious circumstances. Nancy, while balancing school life complete with mean girls and a 12-year-old suitor (whut?), discovers that the movie star may have left an altered last will and testament…and a secret love child! GASP! Of course, Nancy breaks her promise and gets in deep, finding the love child (now a grownup woman played by Rachael Leigh Cook, whom I adore) and putting herself in grave danger!

It’s not a terrible plot, though it isn’t good, but the real problem is that Nancy is not Nancy. The movie uses her name and the basic concept of a teenager who solves all of the mysteries that keep falling into her lap, and tries to make another Veronica Mars (I guess) while ignoring everything that made Nancy stand out. They inexplicably give her a love of everything vintage and retro, dressing her in sweater sets for no reason. She is a little dorky and somewhat clueless, which is the opposite of the self-assured, confident Nancy of the books.

There is one scene in particular that exemplifies the total lack of understand the filmmakers had of the character: Nancy is driving, in pursuit of some bad guy henchmen, and loses them because she refuses to go above the speed limit. Nancy. Drew. Refuses. To. Chase. Henchmen.

(I will preface this by saying that Emma Roberts, who played Nancy, was delightful, as was the entire cast. They were not the problem.)

To save you time, I will summarize the movie: set in modern times, Nancy heads west to Los Angeles (side note, I have always thought River Heights was in California and have just learned that I was wrong) when her father Carson Drew takes a temporary job. He makes her promise to stop taking cases and focus on high school, which she does…but she can’t help herself, and arranges for them to live in the former home of a movie star who lived and died under mysterious circumstances. Nancy, while balancing school life complete with mean girls and a 12-year-old suitor (whut?), discovers that the movie star may have left an altered last will and testament…and a secret love child! GASP! Of course, Nancy breaks her promise and gets in deep, finding the love child (now a grownup woman played by Rachael Leigh Cook, whom I adore) and putting herself in grave danger!

It’s not a terrible plot, though it isn’t good, but the real problem is that Nancy is not Nancy. The movie uses her name and the basic concept of a teenager who solves all of the mysteries that keep falling into her lap, and tries to make another Veronica Mars (I guess) while ignoring everything that made Nancy stand out. They inexplicably give her a love of everything vintage and retro, dressing her in sweater sets for no reason. She is a little dorky and somewhat clueless, which is the opposite of the self-assured, confident Nancy of the books.

There is one scene in particular that exemplifies the total lack of understand the filmmakers had of the character: Nancy is driving, in pursuit of some bad guy henchmen, and loses them because she refuses to go above the speed limit. Nancy. Drew. Refuses. To. Chase. Henchmen.

Nancy Drew was a fashion-forward genius, finished with high school, with a father who fully supported her sleuthing. She was law-abiding, but would absolutely push that boundary to help someone, which is what all of her cases boiled down to. The ‘real’ Nancy wouldn’t let the bad guys get away by being so doggedly good. (I am fairly certain there were no speed limits in the 1930s, so an updated Nancy story needs to consider her responses to other breakable laws in the books and base its characterization on those. Nancy committed so many instances of breaking and entering, trespassing, etc., that I can’t see how having her refuse to speed is consistent characterization.)

Maybe Nancy as she was written is too dull for a modernization, though I don’t really see how. Perhaps the problem is with the men who are writing her now, and lack the imagination to meet the standards of the women whose words formed her story in the first place.

Nancy Drew was a fashion-forward genius, finished with high school, with a father who fully supported her sleuthing. She was law-abiding, but would absolutely push that boundary to help someone, which is what all of her cases boiled down to. The ‘real’ Nancy wouldn’t let the bad guys get away by being so doggedly good. (I am fairly certain there were no speed limits in the 1930s, so an updated Nancy story needs to consider her responses to other breakable laws in the books and base its characterization on those. Nancy committed so many instances of breaking and entering, trespassing, etc., that I can’t see how having her refuse to speed is consistent characterization.)

Maybe Nancy as she was written is too dull for a modernization, though I don’t really see how. Perhaps the problem is with the men who are writing her now, and lack the imagination to meet the standards of the women whose words formed her story in the first place.