What We Say When We Market Queer Stories

I was scrolling through Instagram recently when I came across a post from YA author Malinda Lo, featuring a photo of White Houses by Amy Bloom, a new historical novel about the romantic relationship between Eleanor Roosevelt and Lorena Hickock. Lo, author of awesome queer girl YA novels such as Ash and A Line in the Dark, expressed excitement for the book, but she also had something to say about marketing queer stories to straight people:

“I’m not excited about the Joyce Carol Oates blurb on the cover because it describes their relationship as “secret, scandalous.” What year is this for crying out loud?! Do we still have to sell novels about queer women as scandalous? This isn’t merely a nitpick; using these words still situates queer relationships as abnormal and wrong. Everything I know about this book tells me that’s certainly not Bloom’s intention. Stupid damn blurb.”

I wholeheartedly agree with Lo’s condemnation. Blurbs are tricky, and oftentimes awkward business. To get a blurb from a big-name author may feel like such a victory that it doesn’t matter that such an established and bestselling author slyly suggests the novel exists solely to titillate. Too often, queer history is swept aside or explained away as something that just didn’t happen back then, and Oates’s blurb, no matter how complimentary, reinforces this mindset.

Coming from Oates, this nonsense isn’t surprising. She has a history of making problematic remarks about representation and books in general. Just last year, she made a remark disparaging Mississippians’ ability to read and was gloriously rebutted by Angie Thomas. It’s tempting to shake my head at this particular blurb and think, Ugh, go home, Joyce. Except, this is just one of the many ways that books about and by queer people are positioned as other. It’s indicative of an industry that loudly proclaims #WeNeedDiverseBooks and celebrates Pride, but still enables these micro aggressions against queer people in order to sell queer stories to a straight audience.

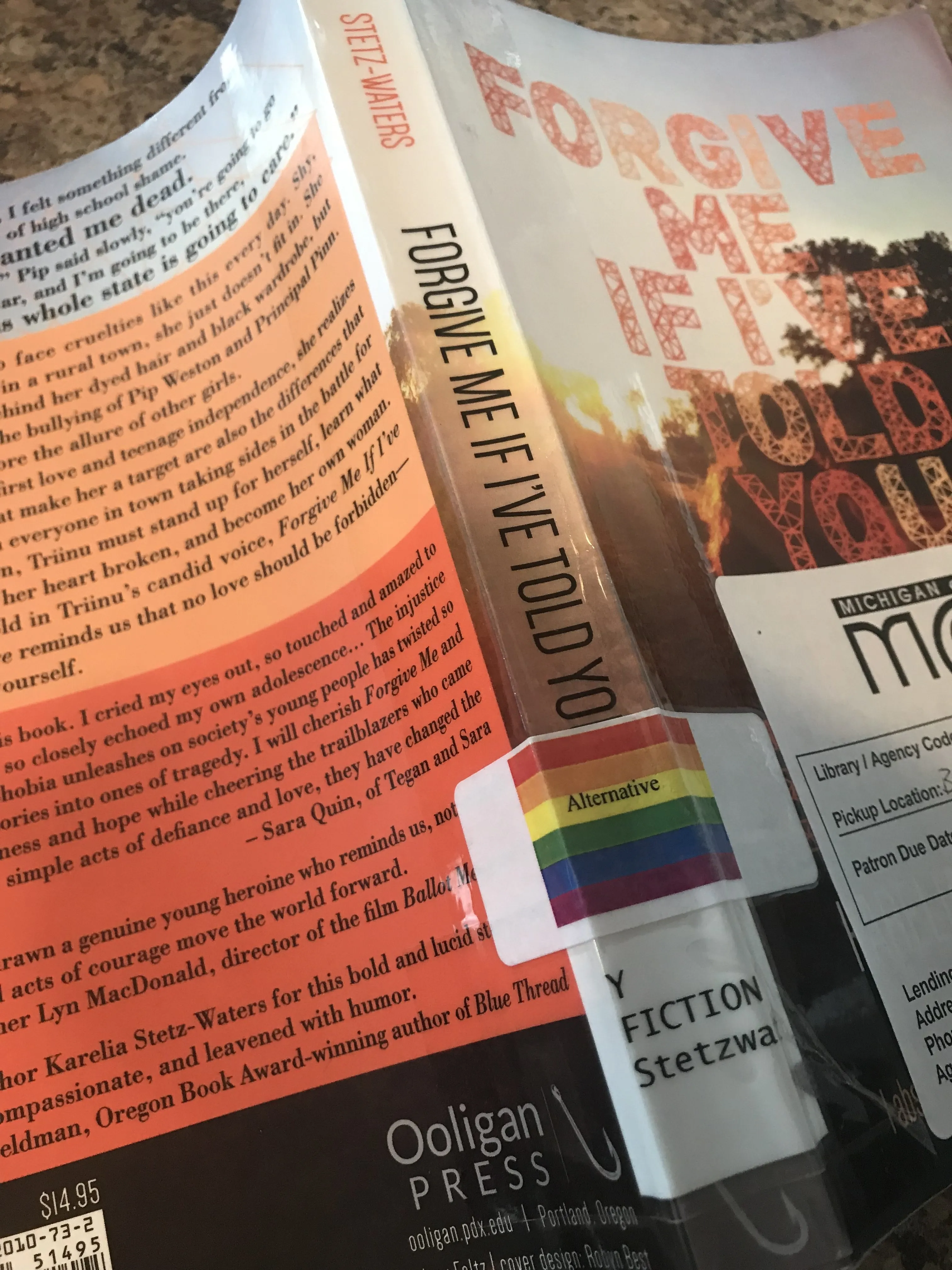

The problem isn’t limited to blurbs and publishing, or marketing queer stories to straight readers, either. After setting down my phone, I decided to start Forgive Me If I’ve Told You This Before by Karelia Stetz-Waters. It’s a YA coming-of-age novel about a teen girl realizing she’s gay just as her home state of Oregon is taking sides on the issue of legislating discrimination against gay people in the early 1990s. I acquired a copy through inter-library loan, and when it arrived, it had this sticker on the spine:

Right above the spine label with the call number, what looks to be a DIY (i.e. not purchased through a library supply company) rainbow sticker, with the word “Alternative” written across it.

As a cataloging librarian in a public library, I know firsthand the task of labeling and cataloging materials in even a small collection is arduous and requires careful consideration of a variety of factors. The goal is to ensure that patrons are able to easily find materials so that they circulate. There is often no one way, or easy way to go about doing this. The debate surrounding integrating LGBTQ+ interest books into a collection vs. designating a special section for them has played out in library land and in bookselling. I touched upon it in my discussion about covers for LGBQT+ YA books in 2016, and I’ve had to confront the question of visibility vs. safety in my own workplace. To be absolutely clear, this rainbow sticker does not offend me. What makes me pause is the word “Alternative,” which begs the question, alternative to what?

Of course, I already know the answer to that. Alternative to straight, and the implication, by extension, is alternative to normal. That one little word changes the conversation from “should we label these books?” (to which there is no easy or right answer) to: Who benefits from this Alternative label? Who suffers from it?

I don’t know anything about the lending library, the community they serve, the collection they’ve curated, or the conversations the librarians must have had about labeling their books. As a fellow librarian, I’m choosing to give them the benefit of the doubt by believing that their DIY sticker is meant to guide, not turn away. But I also wonder if any queer people were involved in the placement of this sticker, in choosing the word “Alternative” to sit in the yellow band of the glorious rainbow flag. I think not. If it were my library, if it were me, I’d fight against that word. I’d fight against that sticker, too, but for much more complicated reasons than I can go into here. I’d want this book, and every other LGBTQ+ interest book, to be shelves alongside books featuring straight relationships, not because they don’t deserved to be celebrated or noticed, but because they should be treated as normal.

Forgive Me If I’ve Told You This Before is a terrific book. It’s a beautifully-written story of friendship and identity (not just sexual, either) set against an interesting back drop of Oregon in the late ’80s and early ’90s. It’s about family and bullying and religion. It’s a book that I know I will be able to wholeheartedly recommend to fans of The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth. It’s also incredibly difficult to read at times. The protagonist, Triinu, faces intense bullying, not just at the hands of her peers, but from adult spiritual leaders, teachers, and administrators in her own high school. When she dares to report a hate note left on her locker, the principal, a proud and outspoken homophobe, tells her she’s exaggerating, that someone is expressing political feelings, not hate speech. Triinu backs down because her safety is at stake. I read that chapter with the paperback pages clutched tightly between my fists, breathing heavily.

It’s not that bad anymore, I tell myself. Things have changed.

Things have changed. Laws have changed, hearts have changed, popular opinion has changed, but ugly ideas still cling, watered-down with enough flashy words and rainbow flags until, if you squint, they’re just pretty enough to slap on the covers and spines of the books we market to readers.