Soft and Quiet: Self-Censorship In An Era of Book Challenges

In the wake of ever-increasing book challenges, legislature meant to silence educators, and hostile board meetings for schools and libraries, what’s gone unsaid is the means by which professionals within these institutions have had to radically alter the ways they select material.

“They’re asking ‘who’s going to complain?’,” explains Anna*, “not ‘who needs this?’”

Anna, who works as a school librarian in suburban Wisconsin, is in an ideal situation when it comes to potential book challenges. Her school, already targeted this year by right-wing censors, has a robust collection development policy and an administration that supports the decisions made by its educators and library staff.

Still, what’s happening inside the school reflects an even-bigger censorship issue: quiet censorship.

Quiet censorship — also known as soft censorship or self-censorship, terms used interchangeably — is when materials are purposefully removed, limited, or never purchased at all despite it being a title that would serve a community. It’s always been an issue with intellectual freedom, but now, with more “parental rights” groups demanding curricular and collection oversight, even the best professionals who don’t believe in censorship are falling victim to choosing the path of considering the people who may complain over those who may need the material.

In Anna’s school, this plays out in several ways.

“I was working with a really bright, innovative teacher who was rethinking how to teach To Kill a Mockingbird in class. We were building a reading list that could supplement the text for her honors class, and based on the teacher’s criteria, I suggested Out Of Darkness by Ashley Hope Perez,” Anna said. “The instructor said to me ‘I can’t afford to add it because of the attention it’d bring.’”

That cost-conscious language is chilling, especially knowing that one of the big goals of the groups pushing for censorship is to create a cascade of time- and dollar-heavy distractions within schools and libraries. This is now not only part of the equation those working in these institutions are considering, but it’s also what makes soft censorship appealing. If the book’s never included, then it can’t create the situation of a challenge or pushback from parents, community members, or those who simply enjoy being part of the disruption of public education.

Anna notes another piece of soft censorship emerging within her school — again, one with all of the supports and structures in place to be a space where any and all choices of material by professionals are respected and regarded as appropriate — is where books are being shelved.

“None of our libraries have purchased Too Bright to See by Kyle Lukoff, despite it being a multi-award-winning middle grade book. If we do buy it, we’ll have a copy in the middle school library, but none in the elementary schools,” she said. “We have a single copy of Melissa by Alex Gino, again in the middle school and not the elementary school. Books about gender or sexuality are put in the middle school and don’t make it to the elementary schools.”

Middle grade books, appropriate for readers from 3rd to 7th or 8th grade, would fit into the elementary school libraries by age and content appropriateness, be it Lexile level, award accolades, and/or critical acclaim. The books haven’t been pulled, per se. But they’ve never had the chance to reach their intended readership. Considering who is going to complain before who needs to see themselves in these books is dangerous and it’s the line of thought those working to ban books seek to create in the minds of those within public institutions.

They’re asking “who’s going to complain,” not “who needs this?”

That pressure becomes a challenge for educators and library workers who wrestle with just how far they can put themselves on the line for a book. Where all parents claim they desire a diverse collection and educational material for their children, the feedback is far less thankful and much more likely to elicit calls of but not like this or this. They game the system, demanding that both sides are played, and the power of censor-friendly groups is much larger than any individual within a library or school, even in supportive environments.

Anna explained: “One teacher told me they couldn’t use Here To Stay by Sara Farizan as a class read because it was about a Muslim person. ‘Someone would yell about that,’ the teacher said. Books like these fit perfect for the curriculum or unit, but now we’re too focused on who might be mad about it and not the value it has.”

Making collection-appropriate choices to serve a diverse world shouldn’t be radical, and yet, thanks to the fears and costs associated with those choices, it is. While educational institutions are short staffed, with fewer people eager to enter these fields because of their politically charged realities and historically low pay, teachers and librarians worry they’ll lose their jobs, healthcare, and entire lives by fighting these battles. This is precisely what’s at stake across the country as more states institute educational gag orders and introduce legislation aimed to create a culture of fear within public institutions like schools and libraries.

An individual’s ethics are unable to withstand the realities of capitalism, and more, by choosing to battle, any individual knows their name will be all over the internet. Their reputation may be smeared by those seeking censorship in ways that impact their ability to even be employed again.

And in many cases, individuals aren’t safe to be whistleblowers inside the institutions where they’re seeing such soft censorship. Middle school librarian Gavin Downing is still employed by Cedar Heights Middle School as a librarian, despite calling out the soft censorship in which his principal engaged. Librarian Brooky Parks, on the other hand, lost her job with High Plains Library District for bringing light to their censorship-friendly programming policy.

If no one speaks up, though, the true breadth of quiet censorship remains unknown.

Ronna Dewey is a parent of three living in the Downingtown Area School District (DASD) in Pennsylvania. Downingtown is about 30 minutes from Lower Merion, the epicenter for one of the largest parental censorship groups in the country, No Left Turn. Moms for Liberty has an active chapter in the area, too.

Beginning in October of 2021, school districts in the Philadelphia suburbs began to see book challenges at their meetings. Among the most notable for Dewey included a challenge at North Penn school district. At the meeting, a challenger wore a Moms for Liberty shirt and read passages from All Boys Aren’t Blue, creating a viral moment for the group as it was shared on Moms for Liberty’s social media.

A board meeting at West Chester Area School District four days later brought a challenge to Gender Queer. It was no normal challenge. The meeting was so disruptive that it made national news and word spread across local social media as well.

Downingtown had been spared so far, but that changed October 27, when the Uwchlan Township Republican Committee shared a blog post on Facebook calling out materials in DASD they believed were sexually explicit and “pornographic.” Four seats on the DASD school board were up in the election that would happen a week later, November 2.

No formal complaint was filed by any individuals associated with the Republican Committee, nor by a parent.

A Facebook post on DASD’s page on October 29, 2021, though, indicated that three books were removed from Downingtown West High School.

Due to “allegedly-inappropriate language and images,” and their appearance on a “nationally-circulating book list,” All Boys Aren’t Blue, Gender Queer, and Me, Earl, and The Dying Girl were immediately removed from the library. That nationally circulating list was either from No Left Turn or Moms for Liberty — these groups operate from using the same lists, scanning pages and creating shareable content on social media that national and local censorship groups use in their complaints.

DASD removed the books without a formal complaint, and Dewey said they never once informed the parents or school community beyond a social media post. Parents would have needed to tune into the November 3 virtual school board meeting to hear about the initial decision to pull the books for review.

The transparency here is far more than in many schools practicing this quiet or soft censorship. But the school has a formal review process, following a formal complaint about material, and these books were pulled because of a circulating list and pressure from groups outside the school. Not because any individual or group followed the proper channels. Notably, the school has an informal complaint policy, too, to which the superintendent is to resolve the matter informally as well.

Of note in the review process in either case is that books will remain accessible for students. Likewise, the policy spells out under its guiding principles that “No parent/guardian has the right to determine instructional reading, viewing, or listening material for students other than his/her own children.”

At the November 3 meeting of the school board, Dr. Emelie Lonardi, Superintendent of DASD updated the board and attendees about the decision to pull the books for review. It’s a disturbing response, particularly for its condescending, anti-intellectual language about what the superintendent wishes she could do to these books, as well as for the clear disregard for the professional judgment of her own staff: She wished she could rip pages out of All Boys Aren’t Blue and that the art in Gender Queer was graphic, like caricatures.

Librarians will need the full support of District administration. Will they get it?

It’s clear that by attempting to pull the books, the school wanted to get ahead of potential social media blowback, especially in the wake of the posts by the local Republican committee. But the school also failed to follow in its own reconsideration policies, removing the books and keeping them off shelves for months — they were not returned to Downingtown West High School until after the January 12 school board meeting.

In the interim between the November and January meetings, the DASD administration formed a committee to reevaluate their reevaluation policies. Further, despite attempts to hide what was going on by addressing it in a circumvent way via Facebook, DASD drew significantly more attention to what they were doing, as seen in the comments section and subsequent update to the initial post. Notably, the update mentions their work on reevaluating the selection policy and that “while we do believe that varied perspectives help to create a more inclusive, well-rounded understanding of our community, we are also sensitive to the age-appropriateness of materials and a parent’s right to decide what is suitable for their child.”

DASD also has a policy for selection of materials, including that selected titles showcase a range of beliefs, experiences, and backgrounds, and that decisions are made with “principle above personal opinion and reason above prejudice in selecting materials.”

Policies and procedures are but paper when not followed, and without question, the superintendent’s personal opinion not only clouds this situation but will impact future decisions made by qualified staff.

The books may be back on shelves while this process is underway, but what concerns Dewey and what should concern any parent in this district is the blatant disregard for their own policy, not just in removing the books without reason, but in their disregard for parental notification beyond the Facebook post. More, the superintendent’s own perspective shades the process, something they pride themselves in not allowing to happen.

“I am concerned that silent censorship will continue. For example, school librarians may be afraid of ordering potentially controversial materials in the future for fear of retribution. I’ve seen several local librarians put on blast on social media and have their jobs threatened. Librarians will need the full support of the District administration. Will they get it?,” asked Dewey.

Dewey’s concern is warranted. Among the proposed changes for DASD book selection for its libraries include each item in the collection being labeled as to its content in the catalog, as well as a recommended age and reading level. Those descriptions might include noting sexual content or graphic violence and new language in the proposed policy gives leeway for personal judgment to make those determinations. Of special concern is this: “Titles that are determined to be pervasively vulgar with respect to language or images and/or contain content that is determined to be morbid, degrading, or excessively interested in sexual matters or work that is not educationally suitable which taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, historical/political, or scientific value will be excluded from the library.”

This is a slippery slope and opens wide the door to soft censorship. Who determines what those standards are within the context of providing a wide and necessary collection of material? If it’s the library staff, what value system do they use to determine appropriate titles? In this particular district, it’s clear where the superintendent stands — she made her feelings well known at a board meeting — and knowing that, library and school workers rightfully fear that their superiors won’t support their decisions.

Instead of fighting for books like Gender Quer or All Boys Aren’t Blue in the future, it might be easier to simply not purchase them at all, as these professionals weigh the choice between who might get mad and who might need the material.

“In the proposed new guidelines,” Dewey explained, “parents will have the opportunity to opt their children out of books, but with no requirement that they need to read a book prior to opting out. Maybe if parents who protested books took the time to actually read them in their entirety, rather than just cherry-picking words, phrases or pictures, they might see how valuable these resources can be.

Passages from Gender Queer have empowered censors. They’ve pulled pages out of context, showing them off at board meetings, sharing them across their groups, marking out talking points to use when they complain.

None of the pages they’re using or citing are the most dangerous.

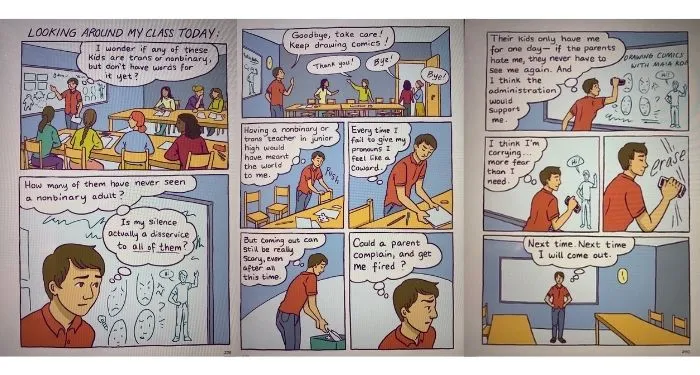

The most dangerous pages are the final three in the book. Kobabe, invited to teach a comics class at a high school, never once mentions eir gender. E doesn’t note eir pronouns. When the class ends and e erases the chalkboard, e wonders about this choice.

“I wonder if any of these kids are trans or nonbinary, but don’t have words for it yet. How many of them have never seen a nonbinary adult?” the thought bubble reads. “Is my silence actually a disservice to them all?”

E continues to consider this in the following two pages. Seeing a trans or nonbinary teacher growing up would have meant the world to em. But e didn’t stand up and say something.

“Every time I fail to give my pronouns I feel like a failure. But coming out can still be really scary, even after all this time.”

As e recycles the papers from the class, e looks out.

“Could a parent complain and get me fired?”

E erases the board and thinks about how the kids will never see em again. Thinks the administration would support em, especially since e’s just there a day.

“I think I’m carrying…more fear than I need.”

The following panel simply reads erase as Maia continues cleanup.

“Next time. Next time I will come out.”

Self-censorship is this promise, again and again and again. It is the impossible decision between who might get mad and who needs to be seen or heard.

*Not her real name.

For more ways to take action against censorship, use this toolkit for how to fight book bans and challenges, as well as this guide to identifying fake news. Then learn how and why you may want to use FOIA to uncover book challenges.