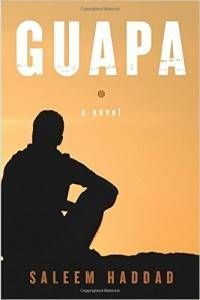

What a Novel About a Gay Arab Man Taught Me About Homophobia

Rasa is woken up in the middle of the night by the screams of his grandmother. Peering through the keyhole, ‘teta’ had caught him in bed with his boyfriend Taymur.

Thus begins Guapa, a debut novel by Saleem Haddad, on a gay man coming of age in an Arab city torn by a revolution-turned-civil war.

Haddad himself is of mixed heritage – he was born in Kuwait to a Lebanese-Palestinian father and an Iraqi-German mother, and worked for Doctors Without Borders in Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Lebanon and Iraq.

His novel comes at an important time – we need to have a conversation about homophobia in the Middle East. I was reminded of how important it is to have that conversation by the horrible massacre in Orlando last night.

Homophobia is part of casual street culture in the region, there is no doubt about that. In the patriarchal, hyper-masculine societies we live in, even the language is biased, the words for top and bottom, khawal and ‘ilq, are themselves casual insults. Lawat, a formal translation of the act of homosexual intercourse, is a reference to the people of the Prophet Lot, Sodom and Gomorrah.

ISIS, the terrorist group rampaging across the region, employs a particularly gruesome punishment – it literally throws gay people off of tall buildings, sending them to plummet to their deaths. It’s ironic that the more outwardly devout you are, the more horrible your track record, given the Qur’an itself declares that taking one life is equivalent to killing all of mankind. “Thou shalt not kill” is apparently more negotiable the more fundamentalist you are. Saudi Arabia and Iran still proscribe the death penalty for homosexuality.

There have been important steps. The judiciary in Lebanon has banned advertisements by psychiatrists claiming to “treat” homosexuality, reasoning that being gay is not an illness. Hamid Sinno, the lead singer of the alternative rock band Mashrou’ Leila, one of the most popular in the region, is openly gay.

But gay Muslims suffer a double ostracization – homophobia by their own co-religionists and those outside the Muslim community, and the Islamophobia raging amidst the rise of right-wing sentiment in the West in general. The recent uprisings in the Middle East have increased awareness of individual rights, but have not led to a conversation about LGBT rights for fear of alienating more conservative members of society. This is why novels like Guapa are important.

Guapa deals with many of these themes. The novel is incredible because it is both truthful and exhilarating – it takes place over 24 hours peppered with reflections and flashbacks as Rasa, a translator and fixer for Western journalists shuttling between the fundamentalists who have taken control of the slums and the authoritarian, disconnected world of the elite that has remained under government control. There is a violence and grit and earthiness to the story, the diesel fumes of the decrepit taxis, the beer-infused underground scent of Guapa, the bar and namesake of the novel, the sweaty embrace of Taymur and Rasa, they are just beyond reach, so visceral that you could almost smell them in the ink adorning the novel’s pages.

But perhaps the most truthful and most painful aspect of the novel is the hypocrisy it depicts. Rasa’s friend Majd, dressed in drag at a late-night party in Guapa, describes the masquerade that is Middle Eastern society, where outward morality belies a much more compromised existence. How can we claim an upstanding morality when our societies and nation-states are crumbling under sectarian division, religious fanaticism, and megalomaniacal psychopaths running our countries, destroying lives and freedoms without a peep from the sanctioned religious clergy? How can we claim the moral high ground while denying the humanity of our brothers and sisters, whether they are gay or on opposing sides of civil wars?

This tyranny of social mores, the concept of ‘ayb or shame, is the province of all Middle Eastern households. For Rasa it’s his teta, a kind of moral police, a guarantor of stability, but every house in the Middle East has a teta, often in the form of a patriarchal head of household, a household dictator that the leaders of our nations, our fathers, are modeled on.

The word for gay in Arabic is shazz. It probably translates directly to ‘queer,’ except that it hasn’t been appropriated. It means different, but it has negative connotations, someone who has disavowed the normal state of affairs. In his flashbacks, Rasa toys with all these different words, looking to see which one of them fits, and struggles with the shame and ‘ayb that his identity bestows on him in Arab society.

Except, we all have some of Rasa in us. Many of us don’t quite feel that we belong here or there, as out of place or equally at home in London and the Egyptian countryside. There is queerness in every one of us who rebelled against tyranny, even in the most die-hard jihadist rebel fighter. Queerness is not just a sexual orientation, it is a rebellion against a calcified social system. It’s part of every one of us. Being different is not a cause for shame because we are all different, nations of minorities all taking our own paths but unable to be ourselves.

We are all Rasa.