The Value of Abandoning a Book

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I’m always interested by the calculations people make in deciding when to abandon a book. The lines they draw in the sand to separate what works for them from what absolutely doesn’t.

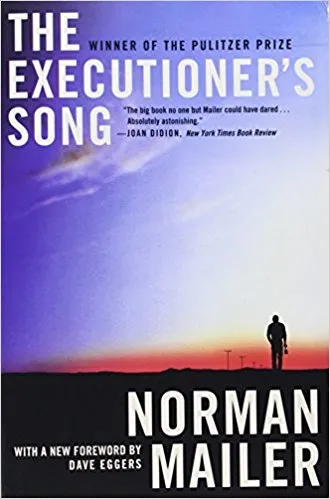

While I agree with these approaches in principle, my own method is quite different. You’ll rarely catch me abandoning a book once I’ve begun. For the most part, I’m committed once I’ve decided to read it. At least, that’s how I was for a long time. It took the right text—or rather, the wrong one—to make me realize the value of abandoning a book. I’m not going to go through all of the volumes I’ve left behind. I merely want to share the book that let the light in—Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979).

Purchased on a true-crime high after I read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Mailer’s 1100-page epic didn’t just show me the value of abandoning a book. It gave me the satisfaction of getting your money back once you return it to the bookstore (true story, and the only time that’s ever happened to me). With my experience of Mailer in mind, I’d like to revisit some popular tests that offer us an escape from a book that just isn’t doing it for us.

While I agree with these approaches in principle, my own method is quite different. You’ll rarely catch me abandoning a book once I’ve begun. For the most part, I’m committed once I’ve decided to read it. At least, that’s how I was for a long time. It took the right text—or rather, the wrong one—to make me realize the value of abandoning a book. I’m not going to go through all of the volumes I’ve left behind. I merely want to share the book that let the light in—Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979).

Purchased on a true-crime high after I read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Mailer’s 1100-page epic didn’t just show me the value of abandoning a book. It gave me the satisfaction of getting your money back once you return it to the bookstore (true story, and the only time that’s ever happened to me). With my experience of Mailer in mind, I’d like to revisit some popular tests that offer us an escape from a book that just isn’t doing it for us.

While I agree with these approaches in principle, my own method is quite different. You’ll rarely catch me abandoning a book once I’ve begun. For the most part, I’m committed once I’ve decided to read it. At least, that’s how I was for a long time. It took the right text—or rather, the wrong one—to make me realize the value of abandoning a book. I’m not going to go through all of the volumes I’ve left behind. I merely want to share the book that let the light in—Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979).

Purchased on a true-crime high after I read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Mailer’s 1100-page epic didn’t just show me the value of abandoning a book. It gave me the satisfaction of getting your money back once you return it to the bookstore (true story, and the only time that’s ever happened to me). With my experience of Mailer in mind, I’d like to revisit some popular tests that offer us an escape from a book that just isn’t doing it for us.

While I agree with these approaches in principle, my own method is quite different. You’ll rarely catch me abandoning a book once I’ve begun. For the most part, I’m committed once I’ve decided to read it. At least, that’s how I was for a long time. It took the right text—or rather, the wrong one—to make me realize the value of abandoning a book. I’m not going to go through all of the volumes I’ve left behind. I merely want to share the book that let the light in—Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979).

Purchased on a true-crime high after I read Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, Mailer’s 1100-page epic didn’t just show me the value of abandoning a book. It gave me the satisfaction of getting your money back once you return it to the bookstore (true story, and the only time that’s ever happened to me). With my experience of Mailer in mind, I’d like to revisit some popular tests that offer us an escape from a book that just isn’t doing it for us.