Scratch and Sniff Books: ’80s Fad or the Future of Children’s Literature?

I set out to write a history of scratch and sniff books, but I found a baffling lack of information. Am I the only one to wonder how this book format came to be and why it never had its moment in the sun alongside scratch and sniff stickers? Or is this a closely guarded secret of the ivory tower, gated from such bookish plebes as myself? Regardless, I’ve pieced together what little I could find online, in scholarly articles, and through crowdsourcing to put together an explanation and timeline. What is the appeal of scratch and sniff books? How did they come to be? And do they have a future?

A Prelude to Scratch and Sniff Books

While humans are not generally known for our sense of smell, our noses are able to detect one trillion odours. Smells also have a strong association with memory, able to bring us back to a long-forgotten moment in childhood in an instant. We already consume books with our eyes, our ears (through audiobooks), and even our hands (both with traditional books and with touch-and-feel books). So why not involve our noses, too? After all, if we want to remember what we read, why not involve the sense linked with memory?

Of course, if you’re reading a physical book, that is inherently a multisensory experience. Bookworms are insufferable in our need to comment on how good books smell, whether you prefer fresh printed pages or an aged vintage fragrance. You can get book smell scented candles or perfume, as well as merch that proclaims you are a proud book sniffer.

This obsession with the smell of books isn’t new, though. In 1992, the French National Archives in Paris had its distinctive scent synthesized and bottled. It is appetizingly described as a “mixture of decaying leather and paper, mustiness and sweat,” which is supposed to remind the smeller of our own mortality (“The Multisensory Experience of Handling and Reading Books” by Charles Spence).

While scratch and sniff books may seem like a gimmick, the incorporation of smell into text is something we’re accustomed to in magazines, where perfume and cologne samples may be included between pages. It’s also been used in advertising, including in The Los Angeles Times in 2007, when they featured a scratch and sniff advertisement for upcoming movies, including one for Mr. Magorium’s Wonder Emporium that smelled like cake (Spence).

Even in the 1950s, some periodicals were printed on scented paper, and one excited author talked about the future of “best smellers,” where cookbooks could be printed on pages which have scents to match the recipe (Spence). Sadly, we have yet to reach the golden age of best smellers, though there is at least one scratch and sniff cookbook: The Scratch + Sniff Bacon Cookbook by Jack Campbell from 2018.

A Timeline of Scratch and Sniff Books

While there had been experiments with scented pages previously, most of the history of the written word, there was a big technological hurdle to matching scents with books. A page sprayed with perfume will have that scent fade fairly quickly. There was no way to mass produce something that would allow a scent to stay strong within the pages of a book while it was being printed, stored, and shipped — the smell would disappear before it made it to the hands of the consumer.

That is, until the 1960s. That’s when the company 3M revolutionized microencapsulation — I won’t bore you with the scientific details, but suffice to say these tiny capsules could contain scents until they were broken (through scratching or rubbing), allowing those smells to last far longer than was possible previously.

Once microencapsulation became cheaper and more common, the 1970s brought the first wave of scratch and sniff books, utilizing this new technology. Little Bunny Follows His Nose by Katherine Howard, published in 1971, is often credited as the first, but I was able to find one published in 1970: The Sweet Smell of Christmas by Patricia Scarry (Richard Scarry’s wife!) Both are Little Golden Book titles, and they’ve both been reprinted many times.

Side note: if you’re a student of classic kidlit, you might be thinking, wait, didn’t Pat the Bunny have a scratch and sniff page, and wasn’t that published in the 1940s? The first edition did not, however: the scented flowers were not added until the third edition.

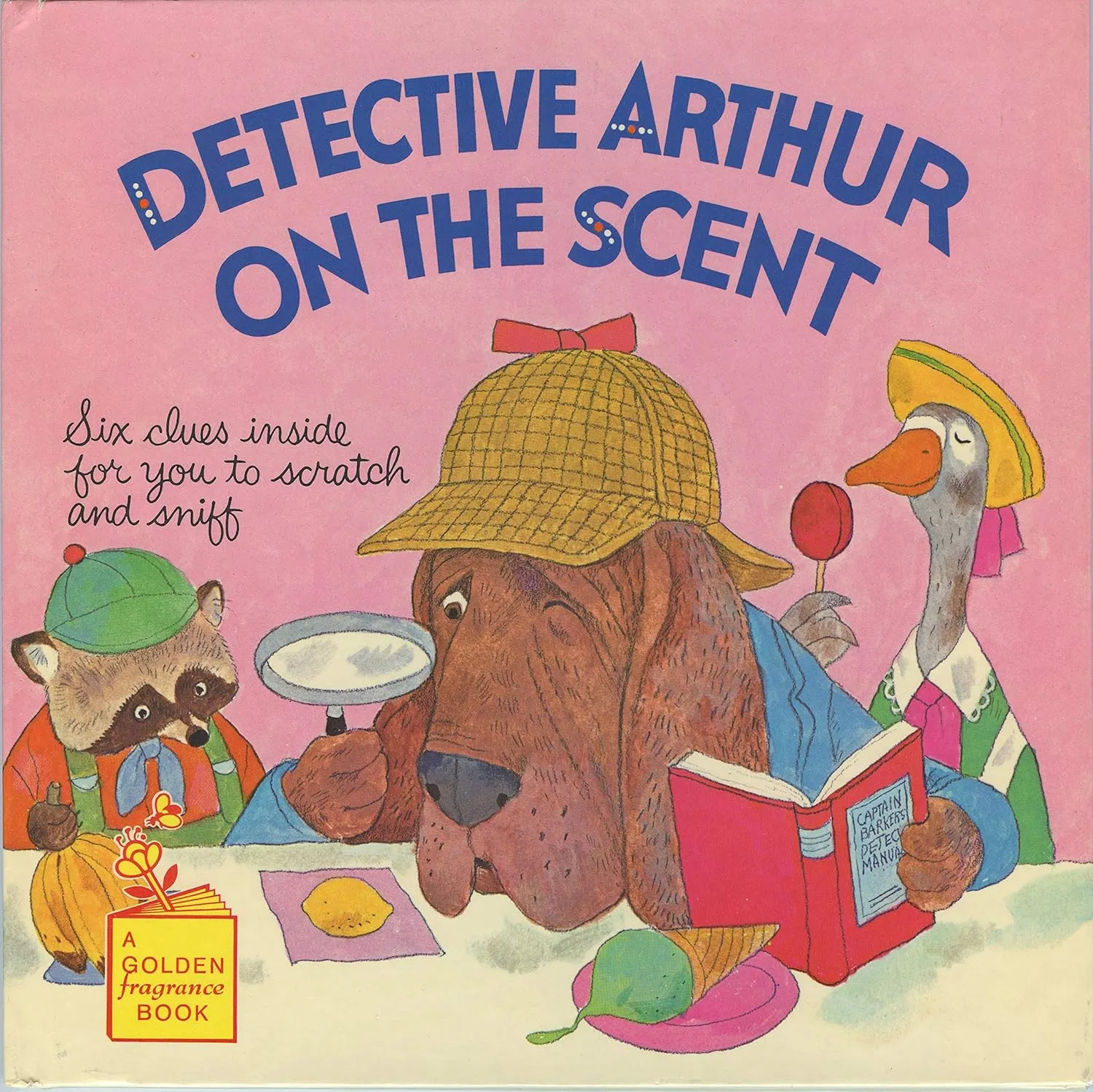

More scratch and sniff books out in 1971 include The Enchanted Island: A Young World Scratch-and-Sniff Book by Desmond Marwood, Cranberry Thanksgiving by Wende and Harry Devlín, Pepito the Naughty Donkey (Fun-to-Sniff Books) by Jennifer Courtney, and Detective Arthur on the Scent (A Golden Fragrance Book) by Mary J. Fulton.

It’s interesting to see how these early examples explain the concept of scratch and sniff, including advertising that they come with “fragrance labels” or “fragrance pictures.” Within a few years, though, “scratch and sniff” was considered self-explanatory.

These early scratch and sniff books were clearly experimental, trying different subject matter and formats. The early 1970s had two different “Fragrance Calendars” for kids: Sniffy’s 1973 Fragrance Calendar and the 1974 Golden Fragrance Calendar. Both of these look absolutely adorable, but I can’t find any “fragrance calendars” published after these two. You can, however, take a peek inside both of them through sold Etsy listings: here is Sniffy’s and here’s the Little Golden Books calendar. You can find your birth month’s scent!

Scholastic even tried a scratch-and-sniff poetry book in 1975: Sniff Poems. Meanwhile, outside the kidlit sphere, Hustler Magazine has a Scratch ‘n’ Sniff centerfold in its August 1977 issue.

The scratch and sniff sticker fad, of course, blew up in the 1980s. But scratch and sniff books didn’t seem to follow: as far as I can find, there were about the same amount of them put out in the 1980s as there were in the ’70s. To use a very imprecise reference, Amazon currently lists about 18 scratch and sniff books published in the ’70s, 13 in the ’80s, and 15 in the ’90s — increasing to 39 in the 2000s, 37 in the 2010s, and 23 so far in the 2020s.

I was expecting to see a spike of books in the ’80s and ’90s — publishing takes so long that a delay between a trend and their adoption seems likely — dropping off afterwards. Instead, the numbers stayed fairly steady: scratch and sniff books seem to have never quite taken off or fully disappeared.

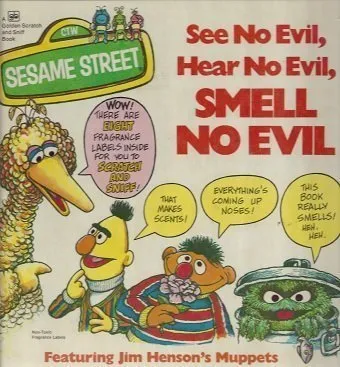

Since the 1990s, they’ve been popular options for franchises: there are multiple Star Wars scratch and sniff books, including A More Wretched Hive: The Mos Eisley Cantina and Fuzzy as an Ewok, as well as scratch and sniff books for Scooby Doo, Winnie the Pooh, Mickey Mouse, Popeye, Ice Age, Paw Patrol, Fancy Nancy, and Sesame Street, to name a few. Not surprisingly, there are several Strawberry Shortcake scratch and sniff books.

From the 1990s onward there were also more adult scratch and sniff books, though they have remained an anomaly. In 1995, there was New York Smells: N.Y.C.’s 1st Scratch & Sniff Guide, which I believe is also the last scratch and sniff guide to New York City — though I did find a recent scratch and sniff guide to Cuba. 2006 brought us Backstage With Beth And Trina: A Scratch-and-Sniff Adventure by Julie Blattberg and Wendi Koontz, which includes the smells of stale beer, cigarettes, marijuana, strawberry lip gloss, and vomit.

The most common kind of adult scratch and sniff books have a common theme: drugs, including alcohol. Published mostly in the late 2010s, there’s The Essential Scratch & Sniff Guide To Becoming A Wine Expert, The Essential Scratch & Sniff Guide To Becoming A Whiskey Know-It-All, The Scratch & Sniff Guide to Beer (not to be confused with The Ultimate Scratch & Sniff Guide to Loving Beer), The Indispensable Scratch & Sniff Guide To Cannabis, and The Scratch & Sniff Book of Weed. (Hey, did you know some dispensaries use scratch and sniff stickers on their bags of weed? Now you know.)

The generous interpretation here would be that smell is an essential part of becoming an expert in things like wine, but the more likely explanation is the shock factor. Scratch and sniff is so closely associated with kids’ books that the adult options tend to be very far away from their picture book counterparts. It’s a shame because there are many topics that a scratch and sniff guide would be useful for, like flower identification or a guide to using herbs in cooking.

Scratch and Sniff Books Today

Now that we’ve seen how scratch and sniff books developed, what do they look like today?

Well, as mentioned earlier, they seem to be holding steady as a rare but never quite disappearing children’s book format. Of course, they’re more expensive to produce than a standard children’s book, but consider this: when I search Amazon for touch and feel books, I get over 30,000 results. The same is true of pop-up books. For scratch and sniff: under 900, and many of those are false matches. Scratch and sniff stickers are cheap, and most kids’ books won’t need custom scents (unlike, say, a guide to whiskey smells). Touch-and-feel books, on the other hand, have a variety of components, including a mix of cloth, plastic, and other textures. I find it hard to believe that they’re more economical than scratch and sniff books, which just add stickers onto board book pages.

Most of the papers I read while researching this topic mentioned the increased interest in “olfaction” in recent years, given that a common symptom of COVID-19 is loss of smell. Even outside of that, though, anyone who has handed a toddler a scratch and sniff book knows they fascinate kids today just as much as they did 10, 20, or 50 years ago — maybe more so, since they’re more used to screens being interactive than paper. Just take a look at these adorable photos of a toddler sticking her whole nose in a scratch and sniff book.

Many people have argued that the reason ebooks never overtook physical books as expected is that reading is a multisensory experience that includes touch and smell (Spence). Parents and kids are more engaged when reading paper books instead of ebooks (JAMA Pediatrics). Kids can physically turn the pages, too, which is interactive. Many readers, children and adults, also appreciate paper books as a break from screens. So why not lean into that interactive advantage of picture books and include more sensory elements, like smell?

As for the kind of scratch and sniff books on the market now, franchises continue to be popular. For original stories, one study looked at the subjects of scratch and sniff books listed on Amazon and found that the vast majority had two themes: food and festivities, like holidays (“Children’s Olfactory Picturebooks: Charting New Trends in Early Childhood Education” by Natalia Ingebretsen Kucirkova and Selim Tosun). Most included five to seven scents per book, though they specifically were looking at stories that incorporated scents, not books where the entire focus is the scratch and sniff elements. The smells included usually represented food or places.

The Future of Scratch and Sniff Books

Scratch and sniff books may have languished in obscurity since their invention, but like with smell-o-vision, we’re still imagining a great multisensory media future.

eBooks and scented books currently don’t overlap, but that could change. In 2014, the oBook (as in “olfactory book”) was invented by Professor David Edwards and his students Rachel Field and Amy Yin (Kucirkova and Tosun). It consisted of a digital book on an iPad connected to Bluetooth-connected aroma dispensers. When certain spots were touched on the screen, smells were released. This was a prototype, but it shows scented ebooks are possible.

Kucirkova and Tosun argue that there are so many more possibilities for olfactory picturebooks. (They stylize picture books as one word.) The best picturebooks, they explain, are ones where the illustrations and text complement — not duplicate — each other. In the same way, then, scratch and sniff books can move beyond duplicating the information in the text and the image. Instead of a page saying “This is an apple” with a picture of an apple and the smell of an apple, smells can be incorporated in a more abstract way. An example they give is the smell of cinnamon for a character with a warm personality, or even as a way to transition between scenes like background music does in film.

In our beautiful future of oBooks, Kucirkova and Tosun imagine that just as font, text size, and brightness could be adjusted, so could smell intensity. Smell could even be used to induce a mood conducive to the story, like incorporating lavender into a bedtime story book.

But Kucirkova and Tosun don’t stop there for a multisensory reading experience. They imagine that with the improvements in both 3D printing and eco-friendly paper alternatives, edible books could be next, which would be a whole new way to interact with a story:

“The intensity of engaging the gustatory sense enables or limits the materiality of an edible book (if readers want to taste the book, the book naturally becomes smaller or disappears). If not consumed, edible books, particularly those created with rice paper, decay over time, so their existence is both reader-contingent and time-contingent. The more readers engage with an edible book, the more they embody the shared space between them and the text, but the more they may render this space immaterial.”

Alas, we are still far from exploring the true potential of scratch and sniff books, never mind olfactory ebooks. In the TV show Pushing Daisies, an author uses scents in a scratch and sniff self-help book to bring success to his readers, truly embodying an abstract incorporation of olfaction that Kucirkova and Tosun be proud of — we can only hope its real-life counterpart will be published next.

Justice for Scratch and Sniff Books!

Thank you for following me through this scratch and sniff literary journey. On reflection, I can see why there isn’t more written on the history of scratch and sniff books: despite being more than 50 years old, scratch and sniff books still seem to be in their infancy. Compared to even other specialty formats like touch and feel books or pop-up books, scratch and sniff books are rare.

Scratch and sniff books are entrancing for toddler readers and can be useful for adult readers, whether it’s by identifying wine by smell or — theoretically — complementing a gardening book. Incorporating scent can make a book more immersive for readers of any age. Smells can affect emotions, and using them thoughtfully can add dimensions to a story.

Unfortunately, most of these uses have either rarely been implemented or are firmly in the hypothetical. The technology is there, and kids tired of screens are eager to stick their noses in the pages of a book. We just need publishers to explore the many possibilities offered by adding another sense to the reading experience.

You might say that in terms of the true potential of scratch and sniff books, we’ve only scratched the surface.

The comments section is moderated according to our community guidelines. Please check them out so we can maintain a safe and supportive community of readers!

Leave a comment

Join All Access to add comments.