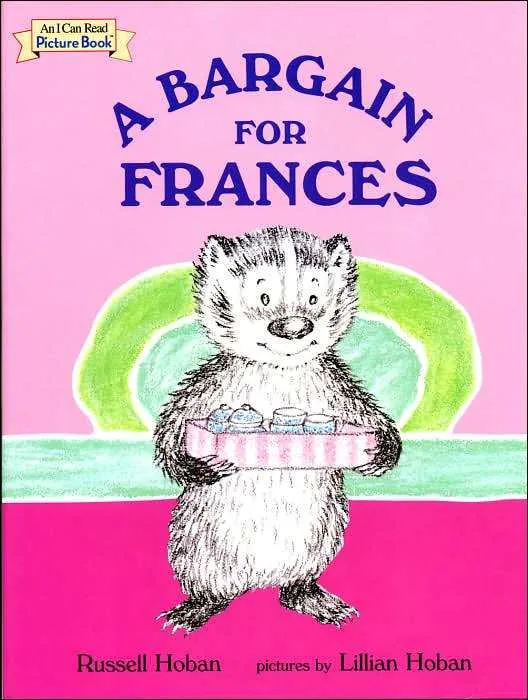

Russell Hoban’s Frances the Badger

Russell Hoban’s “Frances The Badger” #kidlit series was a staple of my childhood. My mom read Bedtime for Frances to me umpteen times, umpteen being defined as so many times that she memorized it and not so many times as I got tired of hearing it. It captured something, this precocious, semi-sweet, and – alright let’s just say it – obnoxious little girl badger. Badger – get it? Frances badgered.

“But Frances’ mom allows Frances to eat only bread and jam,” I told my mom, who said, with what I realize now was humor, “I don’t care what your others friends’ moms are doing.” Frances’ mom is one crazy-like-a-fox badger. She serves Frances a slice of bread and a jar of jam breakfast, lunch, and dinner, without judgement or commentary, until Frances breaks down. “But I thought you only liked bread and jam,” her mom says, feigning surprise, “of course you can have spaghetti and meatballs.”

In Bedtime for Frances, Frances has trouble going to sleep. Not exactly a new trope in children’s literature. What makes it classic is the specificity of Frances’ anxieties. To adults, kids are just scared for no particularly good reason, we call them “formless fears.” But to kids, their fears very much have form. Um, hello? That crack in the ceiling? Spiders could totally come out of there.

Frances’ father, whom she wakes up in the middle of the night with yet another worry, is illustrated perfectly. He opens one eye half-mast, it’s as if he’s been drooling in the deep REM sleep that parents of young children get so little of, and you can tell he just wants to spit and claw, or whatever badgers do. But he keeps it together, and his voice soft. He digs deep for kindness, put on his robe, and goes to investigate wht turns out to be moth banging against Frances’ window. That’s good parenting, I think to myself, as I read it to my children, for what feels like the bazookillionth time. Those badgers are good parents.