A Reader’s Guide to Repealing the 8th

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

In 1983, the people of Ireland went to the polls in a referendum to amend the Constitution of Ireland. 66.9% of the population voted to approve the 8th Amendment, which would recognise the equal right to life of a pregnant woman and the unborn. In 2018, after 35 years of surviving the realities of the 8th Amendment, the people of Ireland returned to the polls and voted to repeal it.

Ireland has long been known as among the last bastions of unborn protection in the western world. Across the world, the repeal of the 8th was seen as a ‘blow to the church’, a surprise from a ‘largely Catholic country’ and ‘a quiet revolution’. It was all of these things, but it was also none of them.

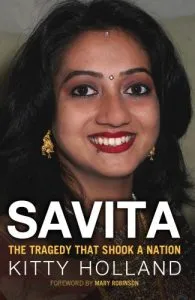

In October 2012, Savita Halappanavar, aged 31 and 17 weeks pregnant, was admitted to a hospital in Galway with her husband Praveen at her side. She was already miscarrying and requested a termination, but was told by medical staff that she could not have one; as there was still a foetal heartbeat, their hands were tied by the constitution. Within two days, Savita had died of heart failure caused by sepsis, after delivering a stillborn baby girl. Savita’s story is laid out with much more expertise by Kitty Holland in Savita, the Tragedy that Shook a Nation.

After her death, protests and vigils were held across Ireland for Savita and online, the campaign came to life in the form of a hashtag: #repealthe8th. For six years, the campaign raged across Ireland before polling day.

For many outside of the country, it is hard to imagine an existence where abortion is banned so comprehensively. Pregnant people who suffered rape, incest or fatal foetal abnormality could not access abortion in Ireland. Seeking an abortion is a crime, punishable by a 14-year prison sentence. Women who sought abortions had to ‘get the boat’, pay for travel to the United Kingdom and seek a termination there, no matter how prohibitively expensive. Drenched in shame and with no aftercare, two generations of Irish people faced this fear alone in the dark.

Over the years, several cases came before the Supreme Court in Ireland, some of which are featured in The Supreme Court by Ruadhan Mac Cormaic—among them, the case of the 14-year-old rape victim known only as X, who swore she would rather die than deliver her rapists’s child. There was also Miss Y, the asylum seeker who was pregnant by rape when she arrived in Ireland and went on hunger strike—she was eventually forced to have the child by way of a cesarean section she did not want. Or Miss P, who was used as a cadaveric incubator for her unborn child after she herself died in a tragic accident; her family had to go to the Supreme Court to have her life support turned off as her body decomposed in a hospital bed.

In October 2012, Savita Halappanavar, aged 31 and 17 weeks pregnant, was admitted to a hospital in Galway with her husband Praveen at her side. She was already miscarrying and requested a termination, but was told by medical staff that she could not have one; as there was still a foetal heartbeat, their hands were tied by the constitution. Within two days, Savita had died of heart failure caused by sepsis, after delivering a stillborn baby girl. Savita’s story is laid out with much more expertise by Kitty Holland in Savita, the Tragedy that Shook a Nation.

After her death, protests and vigils were held across Ireland for Savita and online, the campaign came to life in the form of a hashtag: #repealthe8th. For six years, the campaign raged across Ireland before polling day.

For many outside of the country, it is hard to imagine an existence where abortion is banned so comprehensively. Pregnant people who suffered rape, incest or fatal foetal abnormality could not access abortion in Ireland. Seeking an abortion is a crime, punishable by a 14-year prison sentence. Women who sought abortions had to ‘get the boat’, pay for travel to the United Kingdom and seek a termination there, no matter how prohibitively expensive. Drenched in shame and with no aftercare, two generations of Irish people faced this fear alone in the dark.

Over the years, several cases came before the Supreme Court in Ireland, some of which are featured in The Supreme Court by Ruadhan Mac Cormaic—among them, the case of the 14-year-old rape victim known only as X, who swore she would rather die than deliver her rapists’s child. There was also Miss Y, the asylum seeker who was pregnant by rape when she arrived in Ireland and went on hunger strike—she was eventually forced to have the child by way of a cesarean section she did not want. Or Miss P, who was used as a cadaveric incubator for her unborn child after she herself died in a tragic accident; her family had to go to the Supreme Court to have her life support turned off as her body decomposed in a hospital bed.

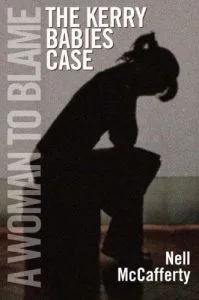

Ireland’s history of mistreating women (and children) is widely known and documented. We have paid a heavy cost for allowing Church institutions to dominate our society for so many generations. Mother and Baby Homes. Magdalene Laundries. Philomena Lee, her lost child and families like hers. Ann Lovett, who gave birth aged 15 at a grotto in rural Ireland, where both she and her child died of hypothermia. The reports of child abuse by senior clerics in the Church. Or the horror story of the Kerry Babies, documented in Nell McCafferty’s A Woman to Blame.

Following Savita’s death and with the start of the campaign to Repeal the 8th, other voices stepped out from the gloom. Women from across Ireland shared their stories—stories of travelling to England for termination help for fatal foetal abnormalities, only to have a baby’s ashes posted back to Ireland by standard mail. Stories of abusive relationships, pregnancies resulting from rape, pregnancies where poverty was set to take too heavy a toll; pregnancies where Irish women simply felt they could not complete because the weight of it would hurt them so much. Pregnancies where little girls were forced to give birth to their own little ones.

Off the back of a popular Facebook page in Ireland, Oh My God What a Complete Aisling by Emer McLysaght and Sarah Breen was a prominent and bestselling novel in Ireland in 2017—and with warmth, humour and dignity, it captured the reality of abortion, the heartbreaking realness of it just how close to home it can come.

Though it was originally seen as a young woman’s campaign, the vote proved beyond doubt that Ireland’s older generations also felt the burn of the 8th and the toil of the shame on their backs. Posters advocating YES and NO votes hung from poles and walls. Leaflets were printed by the thousand and debates were hot headed and miserable. It was heavy and soul-wearying and I think it fractured us a little as a nation; Ireland has healing to do in its aftermath.

I realise this article is incredibly biased in favour of Repealing the 8th Amendment; I was part of the campaign for six long years and was proud that all of my family voted with me. In truth there is not too much published work about maintaining the amendment because it was the status quo for so long—however, Conor O’Riordan’s Debating the Eighth: Repeal or Retain offers a series of essays on both sides of the argument from prominent spokespersons and is worth a read to understand the cultural context. You will notice also that many of the books I mention here were written by women—there is no denying the strength of the feminist movement in Ireland and the overwhelming fact that it changed Ireland forever. This was, predominantly, a women’s revolution.

Ireland’s history of mistreating women (and children) is widely known and documented. We have paid a heavy cost for allowing Church institutions to dominate our society for so many generations. Mother and Baby Homes. Magdalene Laundries. Philomena Lee, her lost child and families like hers. Ann Lovett, who gave birth aged 15 at a grotto in rural Ireland, where both she and her child died of hypothermia. The reports of child abuse by senior clerics in the Church. Or the horror story of the Kerry Babies, documented in Nell McCafferty’s A Woman to Blame.

Following Savita’s death and with the start of the campaign to Repeal the 8th, other voices stepped out from the gloom. Women from across Ireland shared their stories—stories of travelling to England for termination help for fatal foetal abnormalities, only to have a baby’s ashes posted back to Ireland by standard mail. Stories of abusive relationships, pregnancies resulting from rape, pregnancies where poverty was set to take too heavy a toll; pregnancies where Irish women simply felt they could not complete because the weight of it would hurt them so much. Pregnancies where little girls were forced to give birth to their own little ones.

Off the back of a popular Facebook page in Ireland, Oh My God What a Complete Aisling by Emer McLysaght and Sarah Breen was a prominent and bestselling novel in Ireland in 2017—and with warmth, humour and dignity, it captured the reality of abortion, the heartbreaking realness of it just how close to home it can come.

Though it was originally seen as a young woman’s campaign, the vote proved beyond doubt that Ireland’s older generations also felt the burn of the 8th and the toil of the shame on their backs. Posters advocating YES and NO votes hung from poles and walls. Leaflets were printed by the thousand and debates were hot headed and miserable. It was heavy and soul-wearying and I think it fractured us a little as a nation; Ireland has healing to do in its aftermath.

I realise this article is incredibly biased in favour of Repealing the 8th Amendment; I was part of the campaign for six long years and was proud that all of my family voted with me. In truth there is not too much published work about maintaining the amendment because it was the status quo for so long—however, Conor O’Riordan’s Debating the Eighth: Repeal or Retain offers a series of essays on both sides of the argument from prominent spokespersons and is worth a read to understand the cultural context. You will notice also that many of the books I mention here were written by women—there is no denying the strength of the feminist movement in Ireland and the overwhelming fact that it changed Ireland forever. This was, predominantly, a women’s revolution.

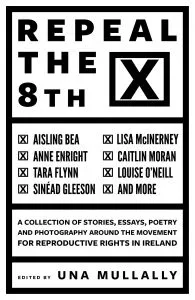

Ireland is a nation of migrants. Last Friday, May 25th, I went #hometovote, with thousands of other Irish people who had the capacity and the money to get there on time. My flight, and many others, were filled with people wearing Repeal jumpers and badges, demanding a better future. I picked up a copy of Repeal the 8th, a collection of creative work edited by Una Mullally, featuring a whole bunch of great feminists including Anne Enright and Tara Flynn.

I voted with my family and returned to the airport. I landed in London to see the Exit Polls come in, estimating a near 70% Yes vote in favour. I sat down at my kitchen table and cried for Savita.

Ireland is a nation of migrants. Last Friday, May 25th, I went #hometovote, with thousands of other Irish people who had the capacity and the money to get there on time. My flight, and many others, were filled with people wearing Repeal jumpers and badges, demanding a better future. I picked up a copy of Repeal the 8th, a collection of creative work edited by Una Mullally, featuring a whole bunch of great feminists including Anne Enright and Tara Flynn.

I voted with my family and returned to the airport. I landed in London to see the Exit Polls come in, estimating a near 70% Yes vote in favour. I sat down at my kitchen table and cried for Savita.

In October 2012, Savita Halappanavar, aged 31 and 17 weeks pregnant, was admitted to a hospital in Galway with her husband Praveen at her side. She was already miscarrying and requested a termination, but was told by medical staff that she could not have one; as there was still a foetal heartbeat, their hands were tied by the constitution. Within two days, Savita had died of heart failure caused by sepsis, after delivering a stillborn baby girl. Savita’s story is laid out with much more expertise by Kitty Holland in Savita, the Tragedy that Shook a Nation.

After her death, protests and vigils were held across Ireland for Savita and online, the campaign came to life in the form of a hashtag: #repealthe8th. For six years, the campaign raged across Ireland before polling day.

For many outside of the country, it is hard to imagine an existence where abortion is banned so comprehensively. Pregnant people who suffered rape, incest or fatal foetal abnormality could not access abortion in Ireland. Seeking an abortion is a crime, punishable by a 14-year prison sentence. Women who sought abortions had to ‘get the boat’, pay for travel to the United Kingdom and seek a termination there, no matter how prohibitively expensive. Drenched in shame and with no aftercare, two generations of Irish people faced this fear alone in the dark.

Over the years, several cases came before the Supreme Court in Ireland, some of which are featured in The Supreme Court by Ruadhan Mac Cormaic—among them, the case of the 14-year-old rape victim known only as X, who swore she would rather die than deliver her rapists’s child. There was also Miss Y, the asylum seeker who was pregnant by rape when she arrived in Ireland and went on hunger strike—she was eventually forced to have the child by way of a cesarean section she did not want. Or Miss P, who was used as a cadaveric incubator for her unborn child after she herself died in a tragic accident; her family had to go to the Supreme Court to have her life support turned off as her body decomposed in a hospital bed.

In October 2012, Savita Halappanavar, aged 31 and 17 weeks pregnant, was admitted to a hospital in Galway with her husband Praveen at her side. She was already miscarrying and requested a termination, but was told by medical staff that she could not have one; as there was still a foetal heartbeat, their hands were tied by the constitution. Within two days, Savita had died of heart failure caused by sepsis, after delivering a stillborn baby girl. Savita’s story is laid out with much more expertise by Kitty Holland in Savita, the Tragedy that Shook a Nation.

After her death, protests and vigils were held across Ireland for Savita and online, the campaign came to life in the form of a hashtag: #repealthe8th. For six years, the campaign raged across Ireland before polling day.

For many outside of the country, it is hard to imagine an existence where abortion is banned so comprehensively. Pregnant people who suffered rape, incest or fatal foetal abnormality could not access abortion in Ireland. Seeking an abortion is a crime, punishable by a 14-year prison sentence. Women who sought abortions had to ‘get the boat’, pay for travel to the United Kingdom and seek a termination there, no matter how prohibitively expensive. Drenched in shame and with no aftercare, two generations of Irish people faced this fear alone in the dark.

Over the years, several cases came before the Supreme Court in Ireland, some of which are featured in The Supreme Court by Ruadhan Mac Cormaic—among them, the case of the 14-year-old rape victim known only as X, who swore she would rather die than deliver her rapists’s child. There was also Miss Y, the asylum seeker who was pregnant by rape when she arrived in Ireland and went on hunger strike—she was eventually forced to have the child by way of a cesarean section she did not want. Or Miss P, who was used as a cadaveric incubator for her unborn child after she herself died in a tragic accident; her family had to go to the Supreme Court to have her life support turned off as her body decomposed in a hospital bed.

Ireland’s history of mistreating women (and children) is widely known and documented. We have paid a heavy cost for allowing Church institutions to dominate our society for so many generations. Mother and Baby Homes. Magdalene Laundries. Philomena Lee, her lost child and families like hers. Ann Lovett, who gave birth aged 15 at a grotto in rural Ireland, where both she and her child died of hypothermia. The reports of child abuse by senior clerics in the Church. Or the horror story of the Kerry Babies, documented in Nell McCafferty’s A Woman to Blame.

Following Savita’s death and with the start of the campaign to Repeal the 8th, other voices stepped out from the gloom. Women from across Ireland shared their stories—stories of travelling to England for termination help for fatal foetal abnormalities, only to have a baby’s ashes posted back to Ireland by standard mail. Stories of abusive relationships, pregnancies resulting from rape, pregnancies where poverty was set to take too heavy a toll; pregnancies where Irish women simply felt they could not complete because the weight of it would hurt them so much. Pregnancies where little girls were forced to give birth to their own little ones.

Off the back of a popular Facebook page in Ireland, Oh My God What a Complete Aisling by Emer McLysaght and Sarah Breen was a prominent and bestselling novel in Ireland in 2017—and with warmth, humour and dignity, it captured the reality of abortion, the heartbreaking realness of it just how close to home it can come.

Though it was originally seen as a young woman’s campaign, the vote proved beyond doubt that Ireland’s older generations also felt the burn of the 8th and the toil of the shame on their backs. Posters advocating YES and NO votes hung from poles and walls. Leaflets were printed by the thousand and debates were hot headed and miserable. It was heavy and soul-wearying and I think it fractured us a little as a nation; Ireland has healing to do in its aftermath.

I realise this article is incredibly biased in favour of Repealing the 8th Amendment; I was part of the campaign for six long years and was proud that all of my family voted with me. In truth there is not too much published work about maintaining the amendment because it was the status quo for so long—however, Conor O’Riordan’s Debating the Eighth: Repeal or Retain offers a series of essays on both sides of the argument from prominent spokespersons and is worth a read to understand the cultural context. You will notice also that many of the books I mention here were written by women—there is no denying the strength of the feminist movement in Ireland and the overwhelming fact that it changed Ireland forever. This was, predominantly, a women’s revolution.

Ireland’s history of mistreating women (and children) is widely known and documented. We have paid a heavy cost for allowing Church institutions to dominate our society for so many generations. Mother and Baby Homes. Magdalene Laundries. Philomena Lee, her lost child and families like hers. Ann Lovett, who gave birth aged 15 at a grotto in rural Ireland, where both she and her child died of hypothermia. The reports of child abuse by senior clerics in the Church. Or the horror story of the Kerry Babies, documented in Nell McCafferty’s A Woman to Blame.

Following Savita’s death and with the start of the campaign to Repeal the 8th, other voices stepped out from the gloom. Women from across Ireland shared their stories—stories of travelling to England for termination help for fatal foetal abnormalities, only to have a baby’s ashes posted back to Ireland by standard mail. Stories of abusive relationships, pregnancies resulting from rape, pregnancies where poverty was set to take too heavy a toll; pregnancies where Irish women simply felt they could not complete because the weight of it would hurt them so much. Pregnancies where little girls were forced to give birth to their own little ones.

Off the back of a popular Facebook page in Ireland, Oh My God What a Complete Aisling by Emer McLysaght and Sarah Breen was a prominent and bestselling novel in Ireland in 2017—and with warmth, humour and dignity, it captured the reality of abortion, the heartbreaking realness of it just how close to home it can come.

Though it was originally seen as a young woman’s campaign, the vote proved beyond doubt that Ireland’s older generations also felt the burn of the 8th and the toil of the shame on their backs. Posters advocating YES and NO votes hung from poles and walls. Leaflets were printed by the thousand and debates were hot headed and miserable. It was heavy and soul-wearying and I think it fractured us a little as a nation; Ireland has healing to do in its aftermath.

I realise this article is incredibly biased in favour of Repealing the 8th Amendment; I was part of the campaign for six long years and was proud that all of my family voted with me. In truth there is not too much published work about maintaining the amendment because it was the status quo for so long—however, Conor O’Riordan’s Debating the Eighth: Repeal or Retain offers a series of essays on both sides of the argument from prominent spokespersons and is worth a read to understand the cultural context. You will notice also that many of the books I mention here were written by women—there is no denying the strength of the feminist movement in Ireland and the overwhelming fact that it changed Ireland forever. This was, predominantly, a women’s revolution.

Ireland is a nation of migrants. Last Friday, May 25th, I went #hometovote, with thousands of other Irish people who had the capacity and the money to get there on time. My flight, and many others, were filled with people wearing Repeal jumpers and badges, demanding a better future. I picked up a copy of Repeal the 8th, a collection of creative work edited by Una Mullally, featuring a whole bunch of great feminists including Anne Enright and Tara Flynn.

I voted with my family and returned to the airport. I landed in London to see the Exit Polls come in, estimating a near 70% Yes vote in favour. I sat down at my kitchen table and cried for Savita.

Ireland is a nation of migrants. Last Friday, May 25th, I went #hometovote, with thousands of other Irish people who had the capacity and the money to get there on time. My flight, and many others, were filled with people wearing Repeal jumpers and badges, demanding a better future. I picked up a copy of Repeal the 8th, a collection of creative work edited by Una Mullally, featuring a whole bunch of great feminists including Anne Enright and Tara Flynn.

I voted with my family and returned to the airport. I landed in London to see the Exit Polls come in, estimating a near 70% Yes vote in favour. I sat down at my kitchen table and cried for Savita.