The Top 10 Adapted Screenplay Oscar Winners, Ranked

Time for the second half of my ranking of the last 20 winners of the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay. (If you missed the first half, you can catch up here.)

#10: BlacKkKlansman

This one plays faster and looser with the truth than I generally like in adaptations. A lot of this happened much differently, and there are things that the people represented did both earlier and later that are…inconvenient for the story Lee and Willmot tell. But I find myself not caring. The movie is electric, raucous, and somehow manages to show the absurdity of white supremacy while taking it deadly seriously. It’s a high-wire act executed with a bit of a shimmy.

#9: Call Me By Your Name

Here is an inspiring fact: Call Me By Your Name screenwriter James Ivory was 89 when the movie came out in 2017. Ivory, of course, is no stranger to lush stories of longing in beautiful places. And while this was more shabby academics on holiday than well-heeled expats, the basic idea still plays: wanting someone you shouldn’t want, getting them, and lo and behold, the things that made it a bad idea are still there. It is just so painful and lovely. And Michael Stuhlberg gets a monologue that I think about often.

#8: 12 Years a Slave

Adapting a 150-year-old slave narrative, whose authorship/transcription is somewhat disputed, is not easy. 12 Years a Slave is brutal and beautiful, harrowing and horrible. I’m glad, though, that the Academy recognized the script, because it was the relationships between the characters, and the various ramifications of the permutations of those relationships, that gave this tour through hell of our own making a humanity that the machinery of slavery was built to destroy.

#7: Sideways

In many ways, this is what I want from a screenplay. Sharp characters, terrific lines, and memorable scene after memorable scene. Flawed characters that we fall in love with all the more because of the specificity of their foibles. Chances are, you’ve drank much more Pinot Noir than you would have if Sideways didn’t make it a sensation. It’s a testament to writing that Sideways is the rare comedy to take home the Oscar in this (or really any) category.

#6: Women Talking

I finally caught this on a plane last summer and was completely blown away. It had been a while since I read the novel, but something about the theater-like setting of the barn intensified the dialogue and interactions between women in a way I wasn’t expecting. I am sure others have compared it to 12 Angry Men, and I wish more movies would realize that a group of people talking passionately about something urgent makes for a great movie.

#5: Moonlight

Books have it a little easier when representing long stretches of time — say, over the course of a lifetime. Part of it is that reading a book for ten hours is just longer than watching a movie for two, especially since that ten hours is likely spread out over several days (or more). You are with the characters longer, so the passage of time feels a little more real as well. With a movie, you have the added problem of needing multiple actors to play a kid and an adult (and sometimes different actors as adults, even). The tripartite structure of Moonlight takes the challenge head-on, following not just one but two characters over decades and across actors. To do this well, you have to pick the right scenes and write them well. Each feels a part of a whole but meaningfully dense on its own. I think Moonlight does this so well that it goes unnoticed. But it shouldn’t.

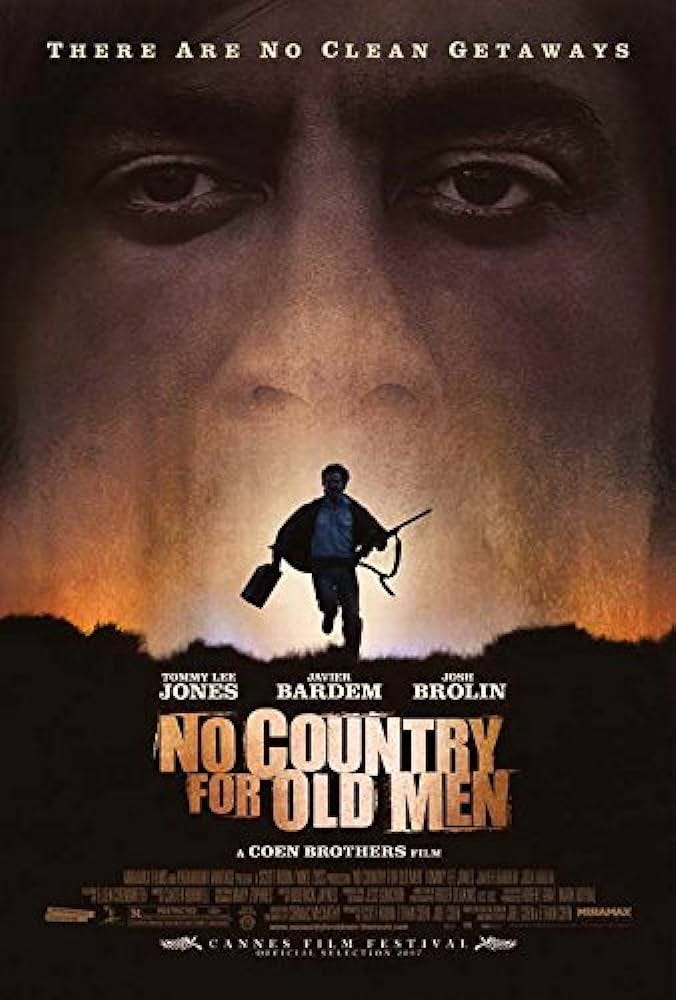

#4: No Country for Old Men

I moved this one around. A lot. I could make a case for it being #1. Also could make a case that McCarthy really did the work and the Coens just didn’t screw it up. No Country has characters you can’t look away from and dialogue so good that it can make you forget there is a gun in the room (this is the opposite of Tarantino, who always writes around the gun in the room). There aren’t a lot of changes to the book, but that is no guarantee of anything. The Sheriff (Jones) and Chigurh (Bardem) are both sharpened rather than dulled, though in that sharpening, perhaps simplified as well.

#2/#3: The Big Short and Moneyball

I have Moneyball on in the background right now. I often have it on in the background. I don’t remember the last time I watched The Big Short from start to finish, but I watch clips all the time (the Jenga tower scene I probably have watched two dozen times). They are very different tonally: Moneyball is Sorkin at his most muted, and The Big Short squeezes every bit of adrenaline it can about a story that is ultimately about numbers on Bloomberg terminals. I think both screenplays are doing the same thing, though: finding characters and moments that we can understand, even if we don’t understand the underlying math. Both scripts are marvels of efficiency, neither eliding complexity nor reveling in it. Both expanded the kinds of nonfiction books that could be made into movies: movies that aren’t just faithful to their source material, but elevate it.

#1: The Social Network

A bizarro version of The West Wing: a group of brilliant near-kids with no sense of duty, little structure, and a shapeless, encompassing ambition. Eisenberg takes Sorkin’s Mensa-level rata-tat-tat dialogue to its absurd conclusion: a flat machine gun of self-serving verbal barbs. Is this how Facebook was made? Not exactly. Is this why Facebook was made? Not exactly. Does it speak to our sense of what it means that Facebook was made? Yes. Is this even a movie about the making of Facebook? Not really. I think of it more as The Godfather of the Silicon Valley era, and much like The Godfather did for the Mafia, The Social Network made the mythology of Zuckerberg, Facebook, tech bros, and digital disruption — even for those in it.

Find more posts like this via our subscription publication, The Deep Dive! Weekly staff-written articles are available free of charge, or you can sign up for a paid subscription to get additional content and access to community features.