On Outlander, Romance, and Diana Gabaldon

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I’m a romance reader, and I came to Outlander through my online romance reading friends. I still remember reading it one summer about eight years ago at a gathering of my college friends on the coast. I hid up in the kids’ sleeping loft, hoping nobody would miss me, as I devoured the love story of Jamie and Claire.

Outlander was recognized by the Romance Writers of America in 1991 as the “Best Romance of the Year.” In 2011, Gabaldon was a featured speaker at the RWA National Meeting, and Outlander consistently ranks as a top romance among readers and experts. In 2015 it made both Goodreads’ Top 100 Romance Novels and NPR’s list of 100 Swoon-worthy Romances.

Not all romance readers love Outlander. Many object to things like Claire’s adultery, Jamie’s beating of Claire, and/or the rendering of Scotland as “Ochlassieland”: gorgeous scenery, handsome, noble Scots, and some scumbag English dudes. And not all readers of the saga are romance readers, either, not by a long shot. But I think it’s fair to say that the romance community has embraced the series. If you have any doubts, I invite you to scroll through some of the 20,000 plus reviews on Amazon. Woman after woman, romance reader after romance reader.

This is why I was disappointed to read, in a recent interview, Diana Gabaldon’s comments about her series not being romance. This isn’t news: she has been saying this for a long time, probably because people keep asking. And most romance readers, including me, would actually agree with her, especially about the second and later books.

But I wish she could speak to her personal view of her books without at the same time making comments about the romance genre that are either dismissive or inaccurate.

Here’s an example:

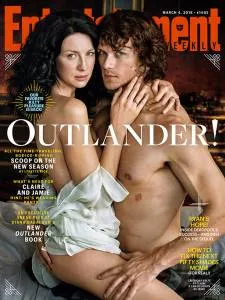

I think she’s spot on about why this magazine cover, and the generally romantic and lusty marketing of Starz Outlander works:

“For those complaining that the EW cover doesn’t properly express the depth, complexity, etc. of the story (books or show)…well…no. It doesn’t. Would you like to suggest a pictorial cover that a) _would_ express that, and b) would appeal instantly to a wide audience? It’s one image; there’s no conceivable way for a single image to encompass this story, or a fraction of it. A magazine cover is meant to do _one_ thing: attract eyeballs. With luck, said eyeballs will zip to Jamie and Claire, but will also see the word “Outlander”.”

I guess I’m not sure why it’s not undignified for TV watchers to be attracted to images like this, or campaigns like “The Kilt Drops.”

In the same Facebook post to her fans, Gabaldon writes “I like well-written romance novels.” Do you find that phrasing kind of odd? Like, would a mystery reader say “I like mysteries. The well-written ones.” I can imagine Gabaldon’s reaction to a reader who approaches her signing table to say, “I really like your books. The well-written ones, I mean.”

I think it would be nice if Diana Gabaldon embraced the very strong romantic elements of her story as much as she embraces the historical elements or the time travel or the literary elements.

I think she’s spot on about why this magazine cover, and the generally romantic and lusty marketing of Starz Outlander works:

“For those complaining that the EW cover doesn’t properly express the depth, complexity, etc. of the story (books or show)…well…no. It doesn’t. Would you like to suggest a pictorial cover that a) _would_ express that, and b) would appeal instantly to a wide audience? It’s one image; there’s no conceivable way for a single image to encompass this story, or a fraction of it. A magazine cover is meant to do _one_ thing: attract eyeballs. With luck, said eyeballs will zip to Jamie and Claire, but will also see the word “Outlander”.”

I guess I’m not sure why it’s not undignified for TV watchers to be attracted to images like this, or campaigns like “The Kilt Drops.”

In the same Facebook post to her fans, Gabaldon writes “I like well-written romance novels.” Do you find that phrasing kind of odd? Like, would a mystery reader say “I like mysteries. The well-written ones.” I can imagine Gabaldon’s reaction to a reader who approaches her signing table to say, “I really like your books. The well-written ones, I mean.”

I think it would be nice if Diana Gabaldon embraced the very strong romantic elements of her story as much as she embraces the historical elements or the time travel or the literary elements.

Once the couple [in a romance novel] is married, that’s the end of the story. And in our story, that means we would have stopped at episode seven.But far from being anti-romance, this trope is so common in historical romance that it has a name: “the marriage of convenience.” Virtual strangers when they marry, Jamie and Claire continue to fall in love and work on their relationship until they reach a point of happiness, unity, and safety at the end of the first novel. Nothing genre-busting about that. In the interview, Gabaldon explains that: “A romance is a courtship story. In the 19th century, the definition of the romance genre was an escape from daily life that included adventure and love and battle. But in the 20th century, that term changed, and now it’s deemed only a love story, specifically a courtship story.” Ok, I guess if a romance is “only a love story,” Outlander doesn’t count. But then, neither do most romance novels. The main protagonists in a romance novel are not just stick figures walking around on a blank page looking for each other. They are people. And people live in a time, at a place, with other people. Yes, the central plot of romance novels is the love story, but in telling that story, romance writers explore history, social issues, ethics, and politics. There’s more: “Finally, my agent called and he said, “Well, they finally decided what to do with your book! The hardcover will go out with the other hardcover fiction, but they’d like to try to sell the paperback as romance.” I had two objections. If you call it a romance, it will never be reviewed by the New York Times or any other respectable literary venue. And that’s okay. I can live with that. But more importantly, you will cut off the entire male half of my readership. They would say, “Oh, well, it’s probably not for me.” So my agent said, “Well, we could insist that they call it science-fiction or fantasy, because of the weird elements, but bear in mind that a bestseller in sci-fi is 50,000 in paperback. A bestseller in romance is 500,000.” And I said, “Well, you’ve got a point!”” I’m a little surprised Gabaldon’s publisher was so stumped. I mean, humankind had figured out how to market multi-genre books before 1991 (Colleen McCullough? Jean Auel? Anne Rice?). But I think she gives marketing departments too much credit for her success. Romance readers didn’t help make Outlander a bestseller because it had a magically magnetic romance label. They chose to read it, they loved it, and they did what readers who love a book do: they shouted it to the rooftops. Sometimes when Gabaldon talks about the importance of the romance label, I picture romance readers as babies who think a toy ball has disappeared when you close your fist around it. Really, we can be trusted to find books with strong romantic elements, even if they aren’t not in the romance section of the book store. The Time Traveler’s Wife, Me Before You, and the Vorkosigan series are just a few examples. I was also puzzled by her worry about the covers: “Provided we had dignified covers — we wouldn’t have bosoms and Fabio and things like that — and also that if the books became visible, they would reposition them as fiction.” I’m not sure I understand this marketing strategy: put on the sheep’s clothing (not too racy, though) for the romance readers, then show the wolf to everyone else? I do understand what she’s saying about romance covers. But I’d rather not call them “undignified.” I mean, undignified for whom? the authors? The cover models? The readers? A lot of readers get a kick out of those clinches, and even find them really beautiful, and who am I to tell them their pleasure is unseemly or beneath them? This point about covers also confuses me a little because Gabaldon has defended some of the racier images of Claire and Jamie. Like this one:

I think she’s spot on about why this magazine cover, and the generally romantic and lusty marketing of Starz Outlander works:

“For those complaining that the EW cover doesn’t properly express the depth, complexity, etc. of the story (books or show)…well…no. It doesn’t. Would you like to suggest a pictorial cover that a) _would_ express that, and b) would appeal instantly to a wide audience? It’s one image; there’s no conceivable way for a single image to encompass this story, or a fraction of it. A magazine cover is meant to do _one_ thing: attract eyeballs. With luck, said eyeballs will zip to Jamie and Claire, but will also see the word “Outlander”.”

I guess I’m not sure why it’s not undignified for TV watchers to be attracted to images like this, or campaigns like “The Kilt Drops.”

In the same Facebook post to her fans, Gabaldon writes “I like well-written romance novels.” Do you find that phrasing kind of odd? Like, would a mystery reader say “I like mysteries. The well-written ones.” I can imagine Gabaldon’s reaction to a reader who approaches her signing table to say, “I really like your books. The well-written ones, I mean.”

I think it would be nice if Diana Gabaldon embraced the very strong romantic elements of her story as much as she embraces the historical elements or the time travel or the literary elements.

I think she’s spot on about why this magazine cover, and the generally romantic and lusty marketing of Starz Outlander works:

“For those complaining that the EW cover doesn’t properly express the depth, complexity, etc. of the story (books or show)…well…no. It doesn’t. Would you like to suggest a pictorial cover that a) _would_ express that, and b) would appeal instantly to a wide audience? It’s one image; there’s no conceivable way for a single image to encompass this story, or a fraction of it. A magazine cover is meant to do _one_ thing: attract eyeballs. With luck, said eyeballs will zip to Jamie and Claire, but will also see the word “Outlander”.”

I guess I’m not sure why it’s not undignified for TV watchers to be attracted to images like this, or campaigns like “The Kilt Drops.”

In the same Facebook post to her fans, Gabaldon writes “I like well-written romance novels.” Do you find that phrasing kind of odd? Like, would a mystery reader say “I like mysteries. The well-written ones.” I can imagine Gabaldon’s reaction to a reader who approaches her signing table to say, “I really like your books. The well-written ones, I mean.”

I think it would be nice if Diana Gabaldon embraced the very strong romantic elements of her story as much as she embraces the historical elements or the time travel or the literary elements.