Why We Should Stop Searching for the Next Gone Girl

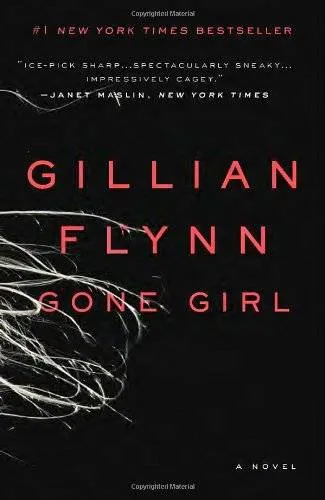

Like many other readers, I was totally engrossed in Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl when I read it. I couldn’t put it down. When the movie came out, I was so excited to go see it. Heck, I even wrote a paper about the novel, which I presented at a conference. I understand the obsession with Gone Girl and everyone’s desire to find a psychological thriller that will recreate that feeling we all got when the big twist hit us. I’ve even been pulled in by the occasional psychological thriller touting itself as the next Gone Girl.

But this has got to stop.

Gone Girl’s Amy Elliott Dunne is a complex character, Flynn’s direct counter to the problematic “strong female character” which has annoyingly purveyed so many narratives for so many years. The problem with the stereotypical “strong female character” is that she’s not allowed to have any flaws. She must do everything perfectly without complaining or showing any weaknesses whatsoever. Often, a “strong female character” is only strong when displaying strength that is coded as masculine.

Amy scoffs at this idea of the perfect woman in her “cool girl” speech; Flynn writes, “for a long time Cool Girl offended me. I used to see men – friends, coworkers, strangers – giddy over these awful pretender women, and I’d want to sit these men down and calmly say: You are not dating a woman, you are dating a woman who has watched too many movies written by socially awkward men who’d like to believe that this kind of woman exists and might kiss them.”

Real women are flawed, in other words. Real women are not fantasies based on male ideals of strength and perfection. And sometimes, as is the case with Amy Dunne, real women are a little crazy. And while it’s totally not okay to treat others the way Amy Dunne treats people in Gone Girl, we enjoy reading her because she’s allowed to be complicated and imperfect and, most importantly, unlikeable in the way that men have been written since… well, forever.

Yet what has risen in Gone Girl’s wake is a new and equally problematic female character archetype – the unwieldy off-the-rails woman. This woman is not any more complicated than the “strong female character.” Her craziness is not a personality, and her bouts of insanity that not even she can control allow for absolutely any twist possible that the writer wants to imagine. How very convenient. How very lazy. How very problematic.

Not only is this an issue from a feminist standpoint – if a woman isn’t boringly perfect, must she be out of control? Can’t we have imperfect female characters who land somewhere in the middle of this dichotomy? – but it is also troubling from a mental health standpoint. In a lot of contemporary trendy thriller novels, mental illness has become a character device used to explain away erratic behavior. Anne Conti in The Couple Next Door (Shari Lapena) blacks out and kills people – but she’s on 50mg of Zoloft and is suffering from postpartum depression, so readers should not be surprised that she’s also insane. Rachel Watson in The Girl on the Train (Paula Hawkins) may or may not have killed a woman, but she can’t be sure; she’s an alcoholic, so anything’s possible.

The stigma around mental illness is already so great. People are afraid to talk about their own struggles with mental health because of what people might think of them. Mentally ill people are seen as dangerous and irresponsible, which can lead to compelling and frightening narratives; however, these are lazy narratives. These are narratives that aren’t representing women or mental illness fairly. Authors have to do better.