Moriarty Was an Afterthought

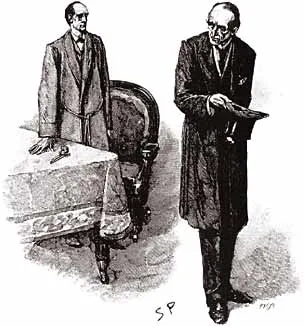

Ask anyone to list literature’s greatest rivalries, and one of the first pairs on the list will undoubtedly be Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty. Even non-Sherlockians are well acquainted with the epic battle of brains and brawn that played out between these two smartest men in England, and with the initially tragic, ultimately triumphant climax to their conflict. This is, at least in part, thanks to the fact that virtually every film and TV adaptation focuses extensively—and, in some cases, all but exclusively—on the enmity between the world’s only consulting detective and the world’s worst mathematics professor.

Frankly, it makes me wonder if the people adapting Doyle’s stories have actually read them.

Huh? Where did all that come from?

In real life, it came from Doyle’s desire to be rid of Sherlock Holmes, a character he’d grown tired of writing. And so he conjured an all-powerful antagonist from thin air and threw him into the story with his usual bored disregard for continuity.

In-universe, an explanation for Moriarty’s rather abrupt introduction can be found in The Final Problem’s second paragraph, where Watson says that “the very intimate relations which had existed between Holmes and myself became to some extent modified” after Watson’s marriage. In other words, they weren’t hanging out so much by this time. If they weren’t speaking regularly, obviously Holmes could not have told Watson about the growing threat Moriarty presented.

Still, it would have taken Moriarty time to amass so vast a criminal empire. Shouldn’t there have been rumblings even before Holmes and Watson’s estrangement? Surely Moriarty’s name should have come up once or twice in an earlier story? It should have, but it doesn’t. Perhaps this is why so many adaptations insist on giving Moriarty the spotlight: to fill in the gaps left by Doyle’s ennui. But with so much else going on in the source material, having every adaptation focus on the same narrow, comparatively minor elements quickly becomes monotonous.

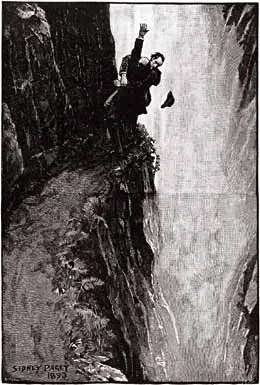

Nor does Moriarty himself actually appear in any Sherlock Holmes story. His actions are related via secondhand flashbacks, told by Holmes to Watson after the fact. Doyle retroactively tried to enhance Moriarty’s role by namedropping him in The Valley of Fear, which takes place before The Final Problem but was published a solid decade after Holmes and Moriarty disappeared at Reichenbach. It is a halfhearted attempt at best and in no way alters the impression that Moriarty was always an afterthought in his creator’s mind.

There’s nothing strictly wrong with this interpretation, but it does get frustrating for people like me, whose attitude towards the naughty professor can be summed up as “Moriarty, Shmoriarty.” Lucky for us, Doyle wrote so many Sherlock Holmes stories and Moriarty occupies such a small space within them that, in terms of the original canon, he is quite easy to ignore.