On MONSTRESS and Mental Health

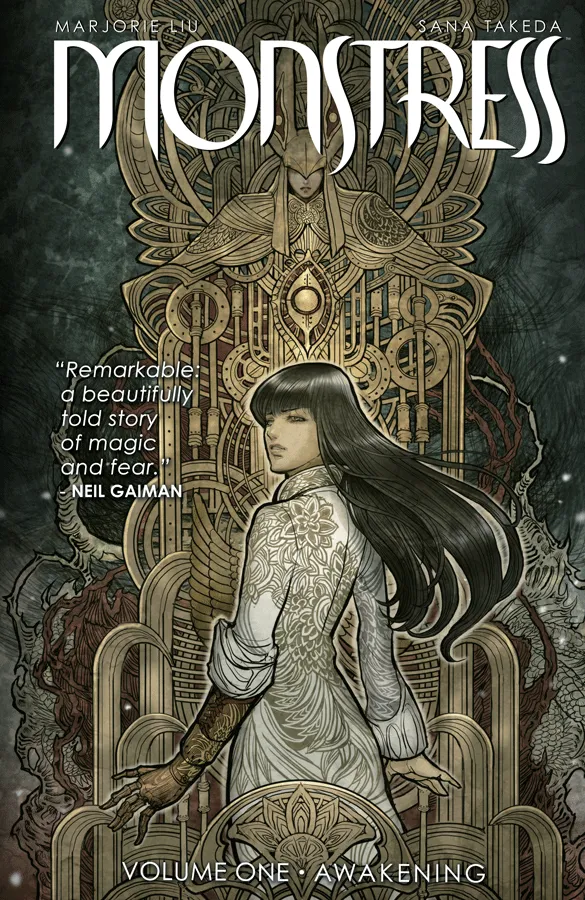

Monstress follows Maika Halfwolf and her companions through an alternate turn-of-the-century Asia as she tries to discover the truth behind what happened to her mother during the war between the Arcanics, magical beings, and the Cumea, a cult of sorceresses. Maika carries within her a powerful dark spirit that she struggles to understand and control, frequently to the detriment of those around her. Maika’s conversations with this spirit revolve around discovering what it is and how it got there, but the questions she asks may sound familiar to readers struggling with mental illnesses. For example, “what are you,” “why are you here,” and “what have you done to me,” among others.

Maybe it’s extreme to assume that everyone with a mental illness personifies said issue to the same extent that Monstress does between Maika and the dark spirit, but the metaphor of a young woman dealing with deeply traumatic experiences facing down a swirling, unknown entity that frequently causes her to lose control is hard to miss. And Liu and Takeda place it smack in the middle of both the plot and the lead character’s development, a move which demands conversation around what is actually happening to Maika. We don’t see this much in popular media, despite how mental health topics gain volume in 2018, and we certainly don’t see it in comics.

One of the things that stood out about Monstress upon its debut was how deeply flawed the mostly-female cast is. Not only do we not get conversations around women and mental health in media, but we especially don’t get to see the messy parts. Learning how to deal with life after trauma—or how to move through the world with crippling anxiety, or how to get out of bed during a depressive spell—is not a clean-cut process, regardless of how you slice it. There are days where we mess up, unintentionally or otherwise, and that’s normal and okay. It isn’t always soft-spoken self care and guided meditations. Sometimes it’s snapping at a friend because you’re anxious or repeatedly canceling plans because you can’t leave the house today. If you’re Maika, maybe you let the dark spirit inside you eat a fellow arcanic.

After infiltrating a Cumea laboratory in search of answers about her mother, Maika escapes with a few rescued Arcanics, expecting to find her friend and traveling companion Tuya waiting for her. Tired of telling her to let go of her violent need for revenge, Tuya has left, passing on the message that she could no longer wait through a talking cat named Ren. Ren then becomes the outside voice to Maika’s constant battle to understand the dark spirit. He breaks the news that, during a black-out where Maika thought she was in conversation with the spirit, she ate one of the rescued Arcanics, an event which prompts Maika to begin shoving her companions as far away as she can despite their insistence on returning. Ren warns Maika to not lose control and to not give in to the dark spirit. His frank tone and refusal to leave Maika on her own makes Ren a welcome presence in Maika’s struggle—even if only to the reader.

It’s important that readers see that even as Maika fights the darkness within herself and shoves her companions away in the process, they continue to come back, to care for her, to guide her as much as they can. Mental illness can be an isolating struggle, especially in a society where we’re told not to talk about it. But no one is alone in that fight.

Despite her messy moments, Maika isn’t interested in fixing her rage, propensity for violence, and need for revenge. But she wants to understand the thing living inside her—she wants information. And she has to travel the far reaches of the continent to find it. This mimics a lot of people’s journey in mental health in that, for an endlessly wide variety of reasons, people seek information that helps them better understand the way they function and why they function that way, with the hope that the end result will be a better quality of life. But the resources aren’t always readily available—not everyone can afford therapy or get to a center where therapy and similar resources are available. It’s a fight, one that in most cases, doesn’t stop in the presence of resources, so much as it just becomes a little easier.

This is what Maika does well in the face of all the darkness contained within her—she doesn’t give in. She keeps fighting and searching and demanding answers. And that’s what it is to live with trauma or mental illness—it’s a daily fight to keep moving. The beauty of Monstress is that Maika gives that fight a name and a face for readers to relate to and pull from in their own struggle. It’s a flawed and complex face to give, but it’s what readers need to see so they can know they’re not alone—whether in a fantasy world or real life.