A Note of Gratitude to Mary Oliver on Her Birthday

Six months ago, at the age of thirty-one, single, and in the middle of a career change, I uprooted my life in a Boston suburb just ten minutes from where I’d grown up, and moved to a tiny island thirty miles off the coast of Massachusetts. After seven years of running my own farm business, I wanted a change. I’d dreamed my whole life of living year-round on the island. There were plenty of reasons not to go, of course. I’d be leaving my family and friends and a business I’d built up over many years. I’d be starting over in a tiny community where I didn’t know anyone.

I moved anyway. Not for any of the typical reasons a person might uproot their life—a job or a partner, for example—but because of the way one particular beach on this island makes me feel. When I walk along this beach, when I look out at the ocean, and the beach grass shimmering in the dunes, I feel something deep and expansive in my heart. It is a physical sensation that no other place on earth has ever evoked in me. In every imaginable weather, windy, rainy, snowy, blazing sun, cool grey clouds—this beach makes my heart beat faster. It is a place I love in a way I have never loved any other place. I moved because I wanted to be closer to that feeling.

Mary Oliver was the first person who ever articulated that kind of love for me.

Her poems, above all else, are love letters to the natural world, and to specific places and parts of that world. She dares to write about lilies and hawks and snakes, about wooded paths and stretches of shoreline, as if these things are as important, as vital, as any human being. She gave me permission to love places in a way I didn’t know I was allowed to love.

I was a geeky, quiet, outdoorsy queer teenager. While other kids my age were at parties, I was spread out on a blanket underneath a tree in my favorite park, reading poetry and scribbling in my journal. I loved books and wild places; I was often anxious around people. Mostly I was happy, but sometimes it weighed on me, this difference between me and my peers. When I read Mary Oliver, I felt seen. I had read other poets of the natural world—Wordsworth, Whitman, Frost—but none of them spoke to me as directly and accessibly as Mary Oliver. Reading her work felt like coming home.

In one of her most famous poems, Wild Geese, she writes:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

In another, The Summer Day, she writes:

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

For years, I repeated the lines of these poems over and over again to myself: You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves. Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? What a revelation! Here was a famous poet—a gay woman, like me—insisting that the deep joy I felt walking along a particular beach or sitting atop a certain mountain was not strange or silly, but the soft animal of my body, loving what it loved. She gave words to that feeling I got in my heart when I lay down on the sand and listened to the waves. Reading those words was both a validation and a celebration of who I was.

Her poems, above all else, are love letters to the natural world, and to specific places and parts of that world. She dares to write about lilies and hawks and snakes, about wooded paths and stretches of shoreline, as if these things are as important, as vital, as any human being. She gave me permission to love places in a way I didn’t know I was allowed to love.

I was a geeky, quiet, outdoorsy queer teenager. While other kids my age were at parties, I was spread out on a blanket underneath a tree in my favorite park, reading poetry and scribbling in my journal. I loved books and wild places; I was often anxious around people. Mostly I was happy, but sometimes it weighed on me, this difference between me and my peers. When I read Mary Oliver, I felt seen. I had read other poets of the natural world—Wordsworth, Whitman, Frost—but none of them spoke to me as directly and accessibly as Mary Oliver. Reading her work felt like coming home.

In one of her most famous poems, Wild Geese, she writes:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

In another, The Summer Day, she writes:

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

For years, I repeated the lines of these poems over and over again to myself: You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves. Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life? What a revelation! Here was a famous poet—a gay woman, like me—insisting that the deep joy I felt walking along a particular beach or sitting atop a certain mountain was not strange or silly, but the soft animal of my body, loving what it loved. She gave words to that feeling I got in my heart when I lay down on the sand and listened to the waves. Reading those words was both a validation and a celebration of who I was.

I can’t say that I moved to this small and beloved island because of Mary Oliver. But I first read her work when I was a young person struggling to figure out who I was in the world, and her poems were part of what shaped me. The way she writes about place—about the natural world—like it is something to love as deeply and honesty and specifically as you love a person—has been the most consistent and important thread running through my adult life. Everything I have done, in one way or another, has been about my love for the specific and inimitable landscape of home.

These days, in the afternoons, I walk my dog along that beloved beach. I look out at the ocean, I feel my heart beating, I feel a deep, deep gratitude welling in my chest. I think of Mary Oliver, of the ordinary courage she poured into her poems, the exaltation of them, radical love of place running through them like a current. Her poems did not save me, exactly; they did not change my life. They reflected back to me the deepest part of myself, and that is an equally extraordinary and humbling gift.

Happiest of birthdays, Mary Oliver, from a deeply grateful lover-of and wonderer-in the world.

I can’t say that I moved to this small and beloved island because of Mary Oliver. But I first read her work when I was a young person struggling to figure out who I was in the world, and her poems were part of what shaped me. The way she writes about place—about the natural world—like it is something to love as deeply and honesty and specifically as you love a person—has been the most consistent and important thread running through my adult life. Everything I have done, in one way or another, has been about my love for the specific and inimitable landscape of home.

These days, in the afternoons, I walk my dog along that beloved beach. I look out at the ocean, I feel my heart beating, I feel a deep, deep gratitude welling in my chest. I think of Mary Oliver, of the ordinary courage she poured into her poems, the exaltation of them, radical love of place running through them like a current. Her poems did not save me, exactly; they did not change my life. They reflected back to me the deepest part of myself, and that is an equally extraordinary and humbling gift.

Happiest of birthdays, Mary Oliver, from a deeply grateful lover-of and wonderer-in the world.

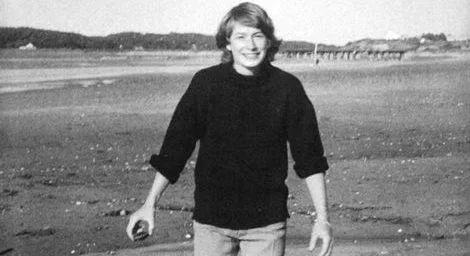

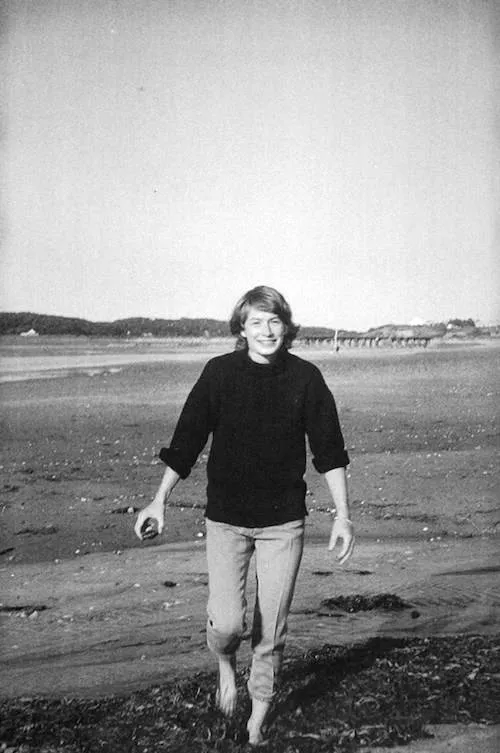

‘My first clam,’ 1964 (Photograph: Molly Malone Cook)

A well-worn copy of Mary Oliver’s New & Selected Poems still gets an honored spot on the shelf by my bed.