MARCH and Racism in America: A Brief Personal Story

In February 2015, my work mentor (who is black) invited me (I am white) to see Ava DuVernay’s MLK biopic Selma.

“I asked my mother if she wanted to come see it,” my mentor said, “but she told me, ‘No. I lived it.'”

I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, where the specters of slavery and Jim Crow sit always at your side. One of the tourist attractions in my (rich, white) suburb is a preserved plantation house from 1845. In the city proper, you can’t find buildings that old; they were destroyed by the Union army on its March to the Sea. Popular historical tours focus on the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s instead – you can visit MLK’s house, church, neighborhood, and, of course, his grave. You can’t truly lionize someone until they’re dead, until they can’t do anything else to complicate their own legacy.

Maybe that’s why I didn’t know much about John Lewis when I was a kid, even though he represented the people of my city.

John Lewis was twenty-three years old in 1963, when he became chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He had already been beaten and arrested for his participation in the Congress of Racial Equality’s Freedom Rides. As SNCC chair, he helped organize the March on Washington, where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Unlike MLK, he lived to see many of the things he’d fought for become law and practice. He went into politics.

In 1986, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives on behalf of Georgia’s 5th District, which contains most of the city of Atlanta (the district has been redrawn multiple times in the last twenty years, but it has never contained my suburb as far as I am aware).

Since 1988 John Lewis has run for reelection fourteen times. In that time he has never received less than 69% of the vote.

At eighteen I moved to Illinois to get my degree, and to generally live in a different part of the country for a while. My randomly assigned roommate was African-American; unlike me, she’d come to school with a group of friends from her high school, which, unlike mine, was predominantly black. They were the first people I hung out with on campus. Early in my first semester they invited me to attend a mock awards show put on by the black student union, starring a group of talented students impersonating Mary J. Blige, Kanye West, Aretha Franklin. I had seen this event advertised around campus over the previous weeks. Until we took our seats, it had never occurred to me that I might be the only white person in attendance. But I was. That was the only time I have been the only person of my color in a room.

The next four years were much the same; no rules or laws or top-down social pressure kept us apart, but students generally socialized by race. I’d need a whole separate post to articulate my hypothesized reasons, but I’m certain at least one was the complacency of white students – myself included. We didn’t turn anyone away, but we didn’t hold our hands out very far, either.

After graduating I moved across Illinois and Indiana, following my husband’s career. We lived in a series of small towns, full of good, hard-working people who tended to believe that racism is “behind us.” They had no knowledge of their own community’s racist history, because there was no battle, the TV cameras never came, and, in some cases, people of color simply didn’t live there. My time north of the Mason-Dixon Line has been the most segregated time of my life.

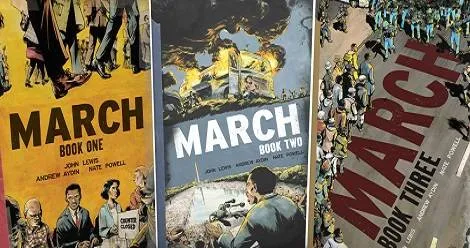

Meanwhile, John Lewis was publishing his memoirs, and he was doing it in a form literary purists might sniff at. John Lewis, pillar of the Civil Rights Movement, was writing a comic book.

I’m not saying racism isn’t a problem in Atlanta – in fact, I want to be very clear that the state of Georgia has a phenomenal problem with racism. I grew up in a place where people saw no essential conflict between naming a major thoroughfare after Ralph Abernathy and celebrating July Fourth at the foot of a giant Confederate monument. Racism is the rot at the core of our nation. But in Atlanta you can’t mothball the people from your textbooks because they’re right there in front of you, visiting their constituents, speaking on the evening news, feeding the homeless, running for mayor, solemnizing the opening of our Civil Rights Museum. As long as they’re alive, they won’t be forgotten.

There is a particularly dangerous racism that comes from forgetting.

John Lewis is now 76. He is the last living speaker from the March on Washington. My mentor’s mother, who doesn’t need Ava DuVernay to teach her about the Civil Rights Movement, is 81. John Lewis won’t be silent until the day he dies. But he will die. All of our freedom fighters will die.

I won’t call March easy to read. As a historian, I’ve paged through hundreds of documents of war and discrimination, and I can tell you that reading about it never gets easier. But a comic book is “easy” in the sense that the barrier to entry is low – it’s not as intimidating as an academic work, and the art can help convey both situational complexity and simple truth.

So it is essential to me that we have this memoir, in this format, in this time. Its National Book Award, announced just five days after Donald Trump’s presidential victory, is a rallying cry: We won’t forget our history. In fact, we’ll make it more accessible. We will read. We will write. We will remember our dead and honor our living.

We will march.