The Malleus Maleficarum, and What It Meant for Witches

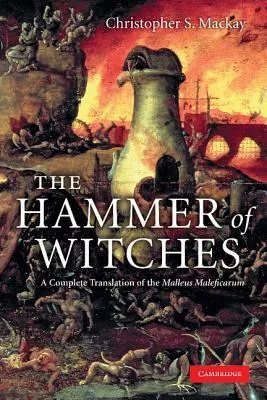

In 1486, a man named Heinrich Kramer, under the name Henricus Institor, decided to publish a treatise about witches, where to find them, and what to do about them: the Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches). His book shifted the way Western Europe (and later the early colonialists in North America), the Catholic Church, and the courts envisioned witchcraft in ways that would have incredible impact. (You have him to thank for our visions of Satan-worshiping packs of sexy women witches dancing in the woods.)

Kramer was one of the first on record to try to actually prosecute alleged witches. It was unsuccessful — he was bumped from his post. Arguably, that’s why he decided to write the Maleficarum. (Side note: he had a co-author, Jacobus Spenger, who was a professor of theology. He was prominent in the spread of reciting the Rosary, and didn’t really like writing all that much, so possibly had a lesser role.)

The Malleus had a scientific approach, laying out all arguments as well as refuting all possible opposing arguments, to defending the existence of witchcraft. Its purpose was to prove that sorcery was real, outline sorceresses’ practices, and give a structure and plan for how to convict and execute witches.

While the the Pope and the Catholic Church weren’t fully sold, and official adoption was sporadic — the Inquisition actually rejected it — the Malleus was a very, very popular book, going into 12 reprints between 1496 and 1519. The later witch hunts were all possible not because the Malleus was taken as law, but because it had shifted the very idea of what witchcraft was and how it was perceived in popular culture, and in doing so, dictated how it should be punished.

Here are the main takeaways of how the Malleus changed the face of witchcraft forever.

WITCHES = Stealing Penises

Here I must, before we go on, share my very favorite part of the Malleus with you, because I share it with everyone I can.

The Malleus tells us that witches very commonly stole male “members” right off their bodies, and that men often had to go and be nice to these witches and politely ask for them back. The text adds:

“As for what pronouncement should be made about those sorceresses who sometimes keep large numbers of these members (twenty or thirty at once) in a bird’s nest or in some cabinet, where the members move as if alive or eat [oats or other feed], as many have seen and the general report relates. It should be said that these things are all carried out through the Devil’s working and illusion.”

He follows that with this story:

“A certain man reported that when he had lost his member and gone to a certain sorceress to regain his well-being, she told the sick man that he should climb a certain tree and granted that he could take whichever one he wanted from the nest, in which there were very many members. When he tried to take a particularly large one, the sorceress said, ‘You shouldn’t take that one,’ adding that it belonged to one of the parish priests.”

(Did the parish priests pay him to write this?)

Just wonderful. Moving on.

Witches = Satanic

When this book was written, magic was viewed differently in Western and Central Europe, primarily through the lens of superstition. People in these regions may, for example, have believed that with certain tools, concoctions, words, or procedures, you could make your neighbor’s cow’s milk dry up, bring on an accident, or cause a woman to miscarry. But it was a local drama, an interpersonal one, punished at most with some time in the stocks, rather than a cosmic or religious issue.

Malleus changed things not because it introduced the idea of magic hiding in our midst, but because it introduced witchcraft as explicitly Satanic. The claim of the Malleus is that that sorcery is part of Satan’s quest to win the final war between hell and heaven. The Catholic church accepted that the Devil was regularly attempting to undermine God’s world and interfere in human affairs to do so. The Malleus establishes witchcraft as a unique heresy: Christopher S. MacKay notes in his introduction to the full translation that this “suggests that the plague of sorceresses is part of Satan’s efforts in the End Days.”

Sorcery, then, becomes satanism. In what scholars call the “the elaborated concept of witchcraft,” witches are not just casual magic users, but have renounced Christianity and entered a pact with the Devil. They assemble in groups, have sex, and practice “maleficent magic” in order to help corrupt the world and help Hell win the ultimate war against Heaven.

“What had previously been simply random instances of misguided activity now took on a far darker significance,” explains MacKay, “and any such activities could readily be taken as proof of adherence to this literally demonic conspiracy.”

And as we approach the apocalypse, according to the Malleus, humanity’s increasing corruption is then punished by God allowing there to be more corruption, as a sort of punishment. This causes then a downward spiral: MacKay writes that “the conception fits with the idea that the apocalyptic end of the world is near and that the perceived recent upsurge in sorcery plays a central role in the downfall of humanity.”

And so, under this narrative, witches become agents of Satan who are actively trying to disrupt our possible future paradise, who are trying to get the apocalypse to come sooner. If you were a believer, this was a terrifying thought, one that required a swift and brutal response.

This paradigm shift in perceptions about witchcraft brought with it an upgrade in severity towards fear of witches throughout Western and Central Europe. Formerly, the Catholic Church had seen witchcraft as misguided, distasteful, or even just as “delusions” caused by the Devil. But if witchcraft was a voluntary pact with the Devil himself, then it was heresy of the highest kind.

And at the time, heresy was a literal crime.

Witches = Heresy

Before 1400, it was rare to go after witches but not rare to go after heretics. Dominican friars would be sent by the Catholic Church to investigate potential heretics, as inquisitors. They were permitted to imprison suspects for years if they suspected guilt, and were permitted to use torture. If the suspects were convicted or considered unrepentant, the inquisitor would turn over the heretic to the secular authorities.

“The inquisitor would hypocritically state in the sentence that he asked the secular arm not to execute the heretic,” says MacKay, “but it was understood by everyone that the heretic was to be executed (normally by being burned alive) in accordance with secular laws against heresy.”

The paradigm shift that witches were demonic, heretics, and to be tried and executed would have consequences for centuries. Witchcraft became not only the purview of demonology and the Church, but a “secular” criminal concern.

And the Malleus did another important thing: it shifted blame squarely onto the shoulders of the corrupted. Witches signed their souls over willingly, corrupted by love, sex, envy, hatred. They entered the pact. The Malleus also emphasizes that witches, rather than the Devil himself, did most of the recruiting either by undermining others and making them need to go to witches for help or by introducing temptations to lure them in.

In other words: witches had no one to blame for their crimes but themselves, and they could be tried accordingly. And so they were: the worst witch hunts in Western and Central Europe were in 1560 and 1630, and we all know about the witch trials in Salem. By linking it with heresy, the Malleus made witchcraft punishable by death.

Witches = Women

Remember the silly things I mentioned earlier about witches stealing penises? Well, it was less funny than I made it sound. The Malleus shares all kinds of things that women can do with their sorcery. They can “turn humans’ minds to love or hatred,” “impede procreation,” “seemingly remove penises,” and “seemingly turn people into beasts.” Oh, and he also mentions “how midwives kill babies or offer them to Satan.”

Seeing a trend?

Men can do magic, and there’s a higher-class magic that gets done in a scholarly fashion as well, but the Malleus only cares about the women, and specifically the lower-class women, and especially the midwives (but we’ll come back to that). The Malleus spends a big chunk of its arguments establishing through the Bible and other “unquestionable” texts that women are loose-tongued, naive, prone to jealousy, and vulnerable — more likely to breach the faith “since they are defective in all the powers of soul and body.”

“The principal cause contributing to the increase of sorceresses is the grievous war between married and unmarried men and women,” claims the Malleus. “Virtually all the kingdoms of the world have been overturned because of women,” it adds. And of course, it all comes back to Eve, because doesn’t it always? His evidence that women are evil is that men, throughout the centuries, have written that women are evil. We are temptresses trying to undermine God’s plans.

It’s no coincidence that witchcraft in the Malleus is linked to both female promiscuity and male impotence. Or that it’s noted explicitly that while in the past sorceresses might have had to be forced to sleep with demons, nowadays they did it willingly. “Everything is governed by carnal lusting,” he concludes, “which is insatiable in them…and for this reason they even cavort with demons to satisfy their lust.”

Witches and women had been associated before, but the Malleus solidified it by proving that women in particular were the kind of witches who were Satan worshippers, who could topple kingdoms and kick us out of paradise, who could put the very battle between heaven and hell at risk for us all.

As you already know, this had consequences: sexual women, or sexy women, or women who men decided they wanted, could be declared witches if they proved to be noncompliant, or temptable, or simply rejected the wrong person. “Turning men into beasts” and “turning humans’ minds to love or hatred” — a woman’s body influencing a man’s mind in the wrong way might, itself, be witchcraft.

Witches = Midwives

Barrenness, sterility, impotence, and pregnancy were all relatively mysterious at the time the Malleus was written. Babies died all the time, as did mothers, and people didn’t always know why. Midwives gave women a fair amount of reassurance by helping them give birth, but there were still so many unknowns. Midwives could help women not conceive. Women had miscarriages, and no one knew how to prevent them.

Which is why it’s interesting who takes the blame, according to the Malleus: the midwives. And they weren’t just witches like the rest. Midwives, according to the Malleus, “surpass all others in evil.”

According to the Malleus, sorceresses can make men impotent, make women sick, and most crucially: murder fetuses and children.

The Malleus refers us to a common idea from its time: the world will head into Judgment Day when the number of people who have risen to heaven equal the number of angels who didn’t fall with the Devil. Unfortunately, midwives intentionally, though sometimes unwillingly, murder newborns. “The reason for this,” MacKay explains in his introduction, “is that the Devil knows that unbaptized children are not allowed into the kingdom of heaven and thus the consummation of the world and the day of judgment that will see the Devil cast into eternal perdition will be put off.”

In other words: midwives kill your children, or “offer them to the demons by devoting them with a curse,” in order to undermine all of our chances at being called up to Heaven once and for all. When a child dies, or a woman miscarries, or a child grows sick, be suspicious of your local midwife. She is on the side of hell.

In one of his first-person recountings, a woman describes how she fired one of her midwives in preference for another, and after the woman curses her in her own home, six months later, the woman suffers “savage torture in the guts,” and it turns out “rose thorns a palm long had been put inside of her along with countless other things.” He then recounts story after story of confessions from midwives who had killed or cursed countless children or made women sick out of bitterness, anger, envy, or vengeance.

Midwives threaten, he seems to say, our very future. These ideas, insidious, would influence future vendettas against local women practicing herbal medicine, against natural remedies and women with old knowledge of pregnancy-preventing potions and ways to ease birth. An institution that gave women more knowledge, more freedom with their bodies, and a certain trust among the women of their community now began to erode. Women could no longer trust those women. Not really.

The perception of witchcraft became linked to midwives, to miscarriage, to the death of newborns, and to barrenness. And so, women were cut off from their best source of local healthcare.

In Conclusion

The Malleus Maleficarum successfully associates witchcraft with a certain kind of emasculating, dangerous, Satan-worshipping woman who is plotting to undermine humanity’s biological future — and so the future of all of our souls — at every turn. Has your baby died, or has your penis stopped working? Maybe it’s that awfully sexy, rather independent midwife down the street. Good news: you can now report her to the local secular authorities.

Thanks to this gloriously misogynistic text, the concept of a “witch” becomes hopelessly braided in with women, female sexuality and pleasure, midwives and unsuccessful reproduction or the death of children — and with being executed, or specifically being burned at the stake.

By linking perceptions of witchcraft with Satan, with deliberate intent, with infant killing, and more, this paradigm shift led to more violence against women, in particular women who appeared to be knowledgable, independent, or empowered. It undermined the power of midwives and of sharing herbal knowledge around sex and procreation, by making that knowledge suspect. There is a straight line from the Malleus to the Salem Witch Trials.

We can blame the Malleus for our concept of witches, and while the idea of sexy female witchcraft has been reclaimed in so many fantastic books and movies, it’s vital to remember that it originally doomed hundreds of women to death — and subjected thousands more to the now-reinforced rabid fear of woman as a temptress set on undermining humanity.