Making Maps for Books: Two Cartographers Tell Us How It’s Done

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

How exactly does one go about making a map of a make-believe place?

To find out, I contacted some publishers, and they hooked us up with their mapmakers, who told us how they work with authors, how they draw maps, and what they’ve contributed to the fictional worlds they draw.

So sit back, and prepare to travel without moving, as cartographers Tim Paul and Rhys Davies take us through the process of making a map of a place that doesn’t exist.

Who decides to include the map? The publisher or the author?

According to Lauren Panepinto, creative director for Orbit Books, the decision to include a map in a book is usually up to the author, although the publishing house does have some say, particularly if the author’s map spoils aspects of a story.

“Many authors keep maps of differing levels of complexity as a writing tool, and those get passed along to me through the editor, and we discuss whether a map will enhance the reader experience,” she says. “In most cases it does, but sometimes there’s an aspect you don’t want to reveal yet, so we may do maps later in the series, or have different maps of different parts of the world in different books.”The process is similar at Prometheus’s sci-fi and fantasy imprint, Pyr, according to editorial director Rene Sears. Usually the author happens to have a map on hand already and passes it on to the publishers.

“Most often at Pyr that map starts with the author,” she says, “either to help them keep track of where their protagonist has been or is headed, or as a world-building exercise in and of itself. From there, Pyr finds an artist to translate the author’s map — which might be very elaborate or might be not much more than a scrawl — into something that will not only help the reader get a sense of place but add aesthetically to the finished book.”

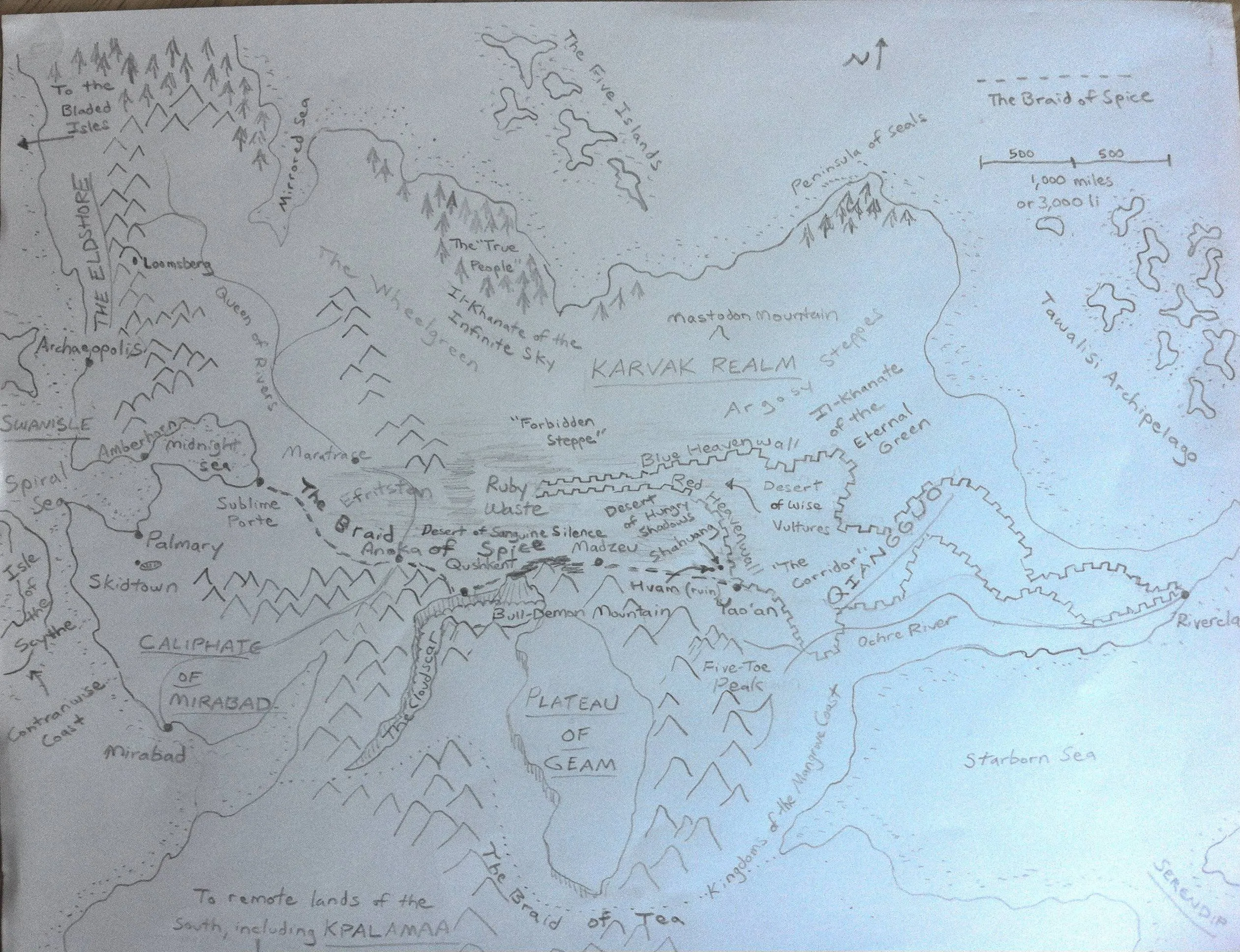

- Author sketch of the map from Chris Willrich’s THE SILK MAP.

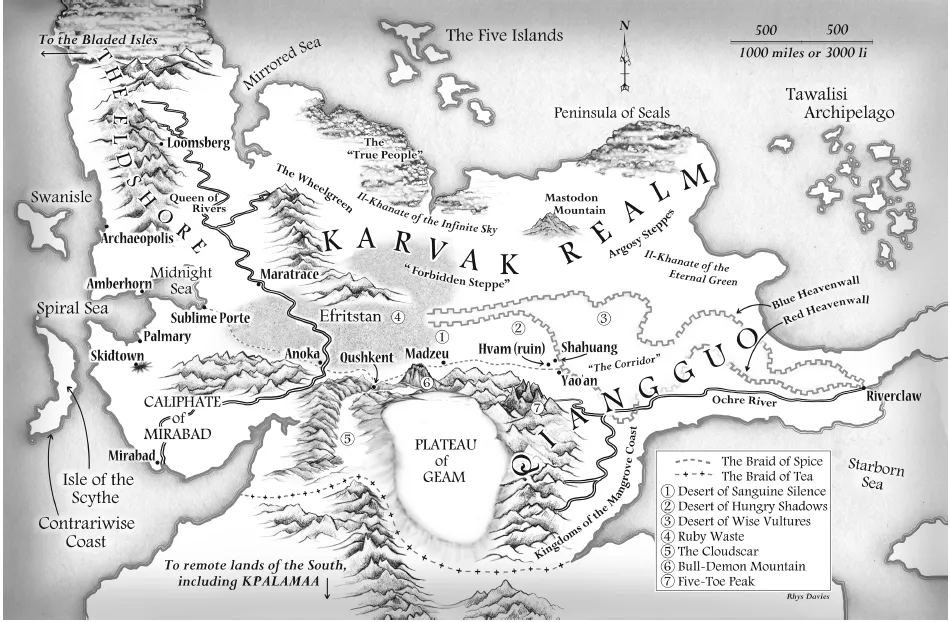

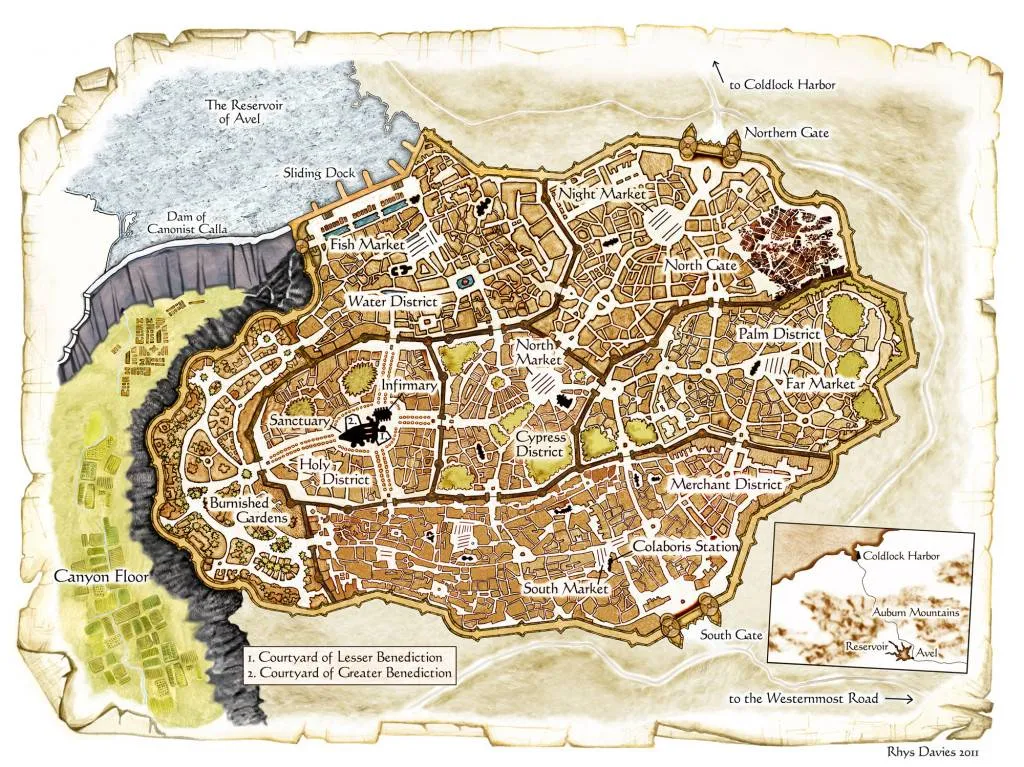

- The final map from Chris Willrich’s THE SILK MAP, by Rhys Davies.

Left, Author sketch of the map from Chris Willrich’s THE SILK MAP. Right, the final map by Rhys Davies

That’s where the artists come in.“You really need someone that specializes in maps, because it can be extremely tedious work if you’re not attracted to that aspect,” said Panepinto. “You also can’t just have any cartographer do the map — remember, these are maps of places that don’t exist! They need to be drawn out of the author’s mind and then illustrated.”But wait. How does one get into making maps of imaginary places? Tim Paul, who makes maps for Orbit as well as other clients, has been an artist all his life, majoring in Fine Art Figure Drawing at Wayne State University and working as an illustrator. His expertise as a mapmaker, however, comes from another passion of his: Paul has been playing Dungeons & Dragons since the age of 14.

“I always loved making my own worlds and maps for Dungeons and Dragons,” he said. “But it took a while to put together that illustration and map-making can go together.”Rhys Davies, a mapmaker who has worked with Pyr and Tor, is also a trained artist who specialized in fine art at art school. He came to map-making after leaving a product design job at Yankee Candle. (He was fed up with drawing birdhouses and snowmen, he says.) “A friend at St. Martins/Macmillan put me on to a wonderful art director at Tor who needed a map for a new series of novels.” The books were Charles Brokaw’s Code books. “It all tumbled on from there,” he said. Fun fact: When asked if they had a favorite map growing up, both Paul and Davies immediately pointed to J.R.R. Tolkien’s map of Middle Earth. (“For me there is only one fantasy map,” said Davies.) From the author’s mind to the fly-leaf Map artists need two things from an author: a list of all the names and places that are going to be on the map and a rough draft of the map itself. Some of those roughs are turned in on anything from scraps of paper to napkins, but others, says Davies, are clearly planned out.

“Most authors do have a rough sketch of their world, if for their own reference,” said Paul. “I’ve gotten very rough sketches, where just the names of the countries have been placed on a paper, showing their location to each other, to more detailed drawings.”

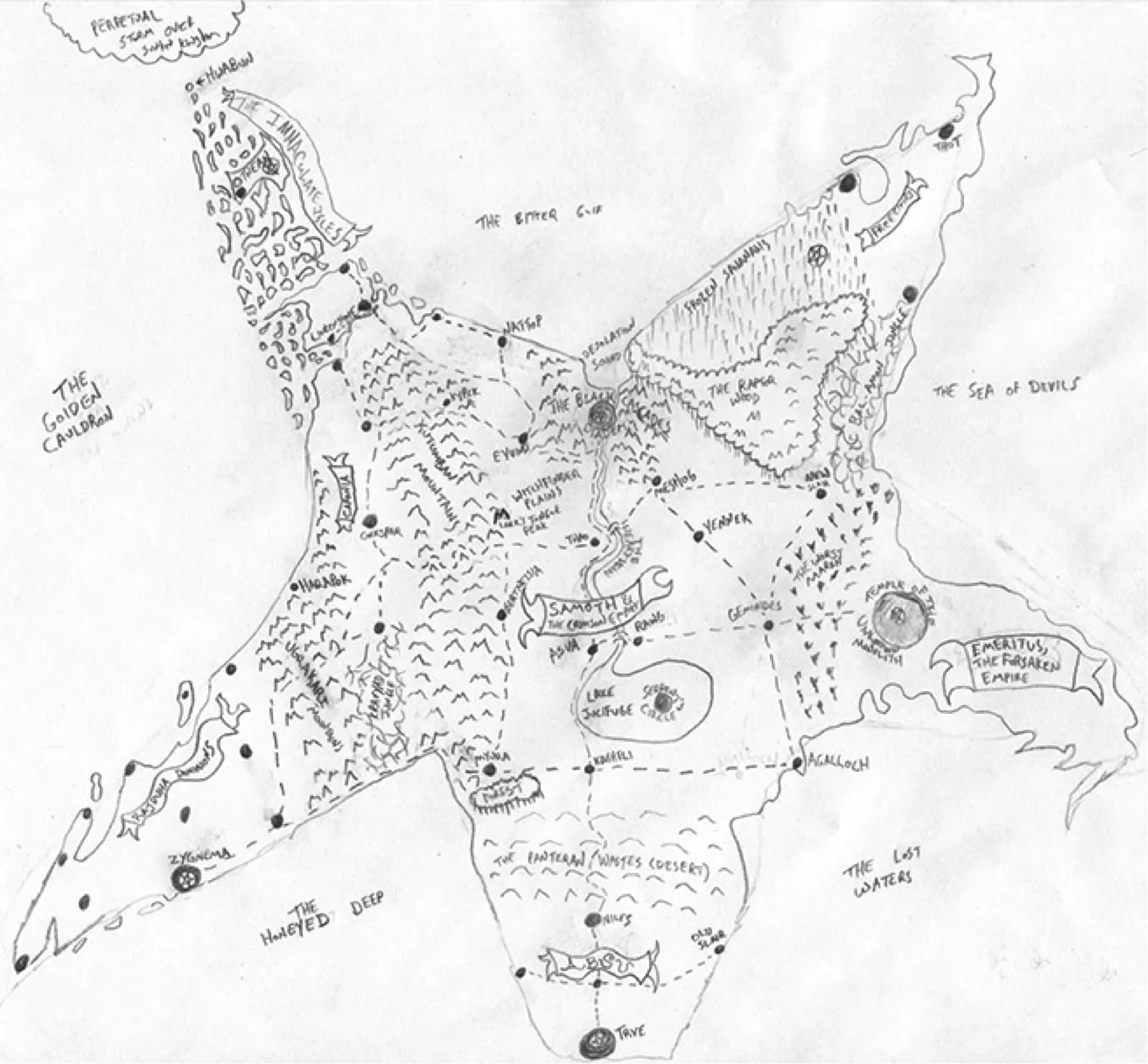

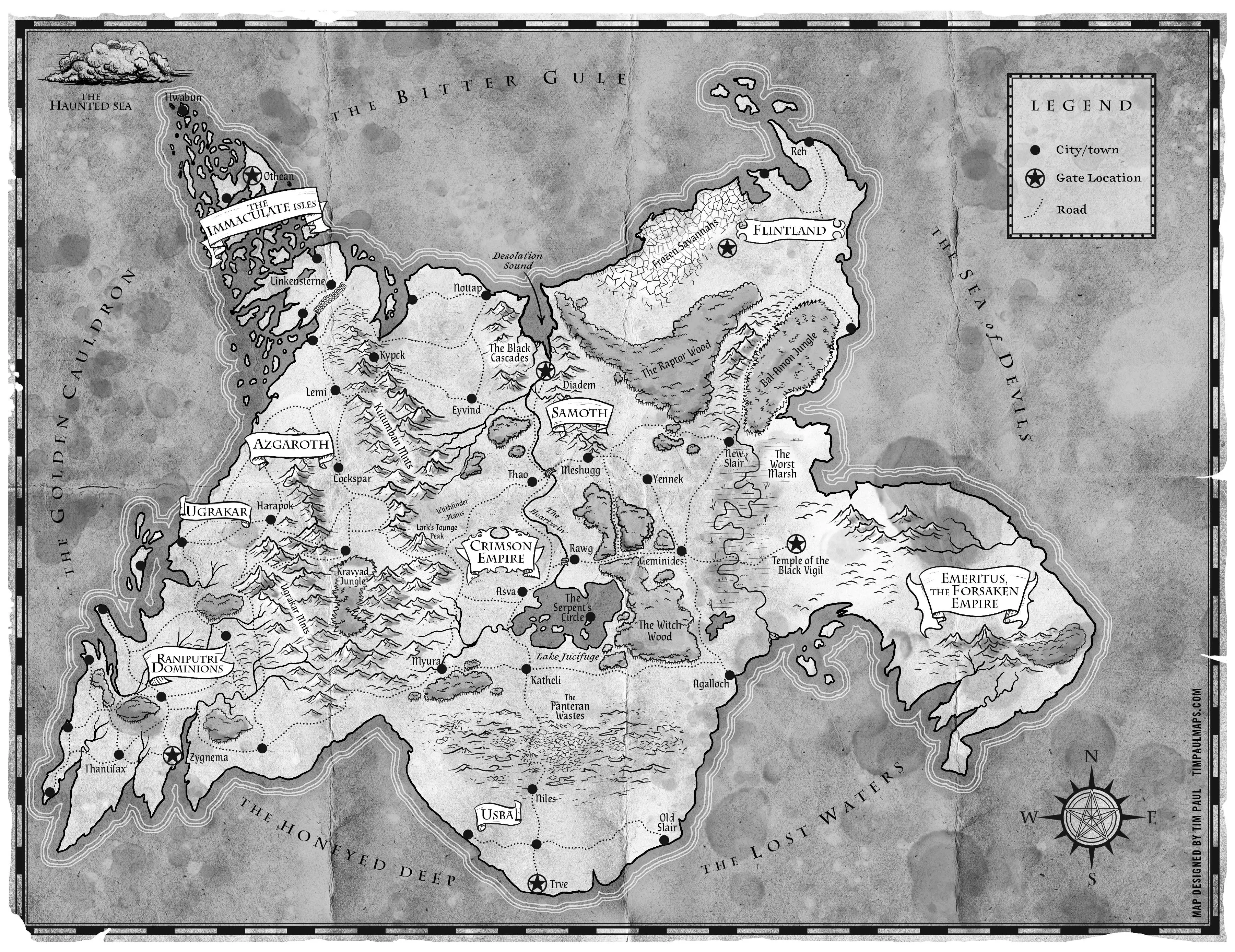

- Author sketch of the map for Alex Marshall’s A CROWN FOR COLD SILVER

- Tim Paul’s in-progress map.

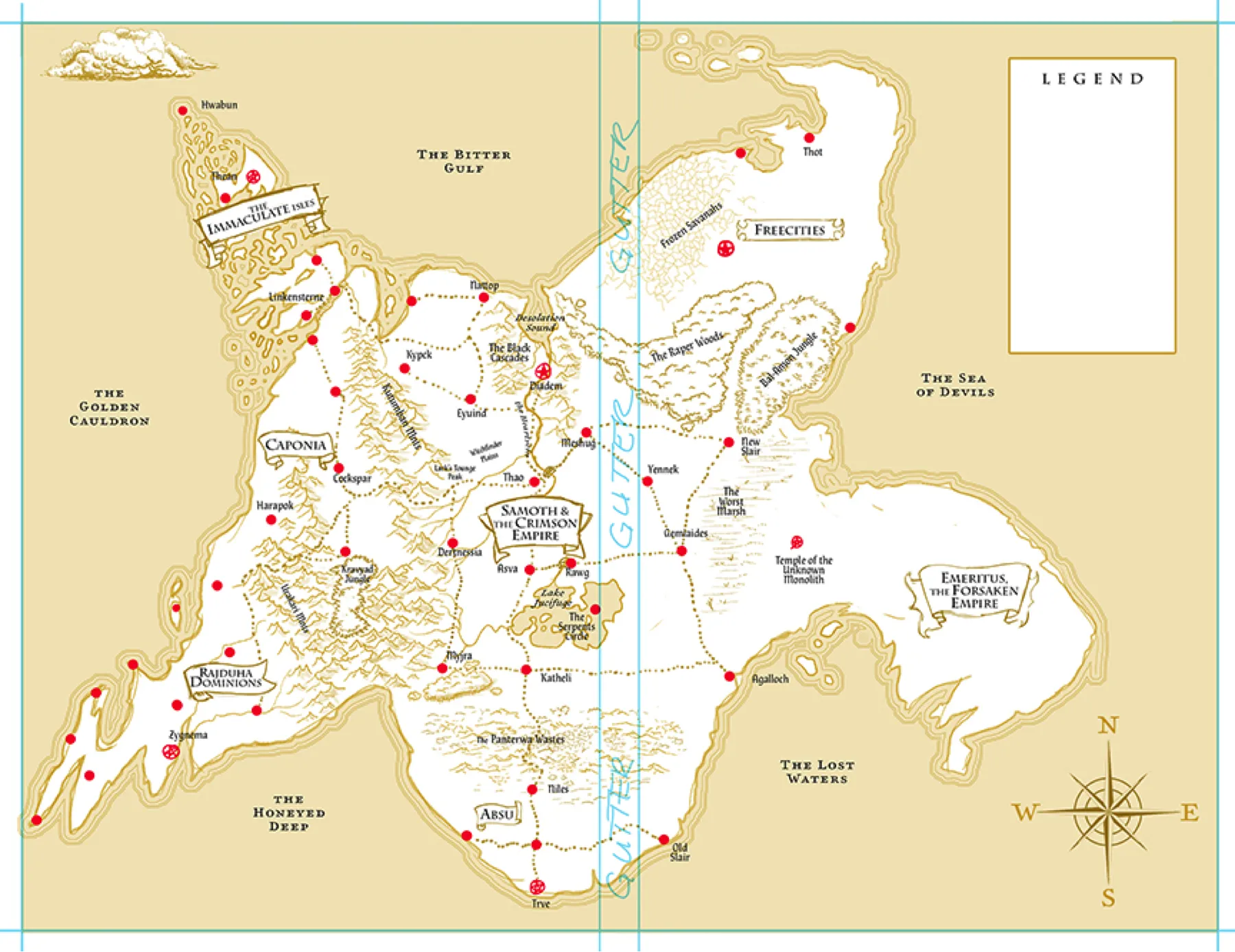

- The final map

From top left, clockwise: Author sketch of the map for Alex Marshall’s A Crown for Cold Silver. Tim Paul’s in-progress map. The final map.

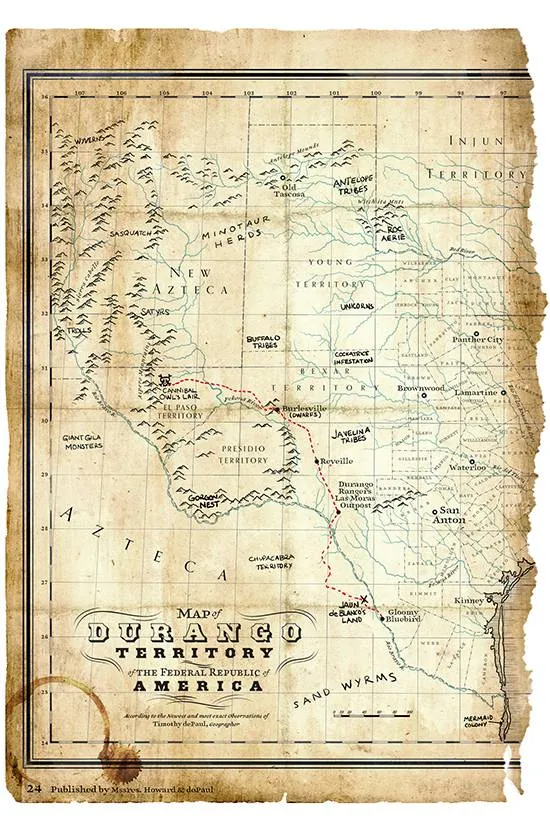

Occasionally, but not often, mapmakers get to read a copy of the book. This was the case for Paul, who had a chance to read Wake of Vultures by Lila Brown before making the map (the Wake of Vultures map is currently his favorite).“I really wanted to make a map that could easily be an artifact from the world of the book,” he said. “I came up with the idea that the map could be a page ripped from an atlas, and someone had written notes on it. Both Lauren and the author liked this idea. I then got to stick in a couple of little details that only a few people will get. I love stuff like that.”Both Paul and Davies usually begin drafting their maps by hand. Davies works by hand before turning to Photoshop to clean things up, fine-tune his work and add old paper textures to the finished product (he uses different textures for the land, the sea, etc.). For Paul, who uses a Cintiq touchscreen, working by hand also means he’s working electronically.

“Once the information is processed, and I start, the process is pretty much the same for each map,” said Paul. “I draw a rough pencil, and place all the names, and other map elements, such as grids, compass roses, cartouches, and borders. I’m just going for placement and accuracy.”The maps also have to be tweaked so that they fit on the page.

“If it’s a double page map consider that there needs to be a clear space down the middle for the gutter,” said Davies. “You can’t have any crucial towns or details fall into the gutter.”Real world geography vs. fantasy geography The artists send their maps to the authors for feedback; at this point, there can be a lot of back-and-forth, or “tennis-matching”, as Davies calls it. The author needs to make sure the map is consistent with the story and the mapmaker needs to make sure the map makes sense. For the second book in Blake Charlton’s Spellwright series, Spellbound, Davies and the author worked together to create a map of a city, and Davies found that he needed to make the city believable; he and the author had to decide on a workable street pattern and Davies had to draw buildings that corresponded with the income of the inhabitants in certain neighborhoods. Does the geography of a fantasy map have to match real world geography? That depends on the mapmaker and the author. Davies, who also creates real world maps for other genres (real maps are most challenging because accuracy is key, he says), does sometimes adjust rivers so that they don’t flow uphill. Paul does the same, but for the most part, isn’t too bothered by geography that doesn’t match the real geography of our own planet. “These are fantasy worlds and anything is possible, so me personally, I don’t stick to the 100 percent authentic possible geography concept,” he said. Mapmakers are world builders, too According to Panepinto, the mapmaker is as much of a world builder as the author is. Davies is hesitant about calling himself a world builder; the author, he says, is the one with the true vision of his or her world. He did mention, however, that one of the authors he had worked with was using the map Davies had drawn for his first book as a reference for the next book in a series.

“I did once get a note from an author who, after seeing the finished map, realized that he’d got a geographical element really wrong in his first book and was going to revisit a particular city in the next book after studying the map,” he said. “That felt a little bit like my being the hand of god!”Paul has had similar experiences — an author has changed a small detail in the book to match the map — and that does make him feel like a world builder. Mostly, however, he feels like a world builder because his work sets up a book.

“A map comes before the text in most books, and a good map can help set up, in the mind of the reader, what they might expect before they read a word. You can visually help set the stage in a very subtle way with how you make your map. That’s a visual form of world building.”