Weird and New Weirder: An Interview with Jeff Vandermeer

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

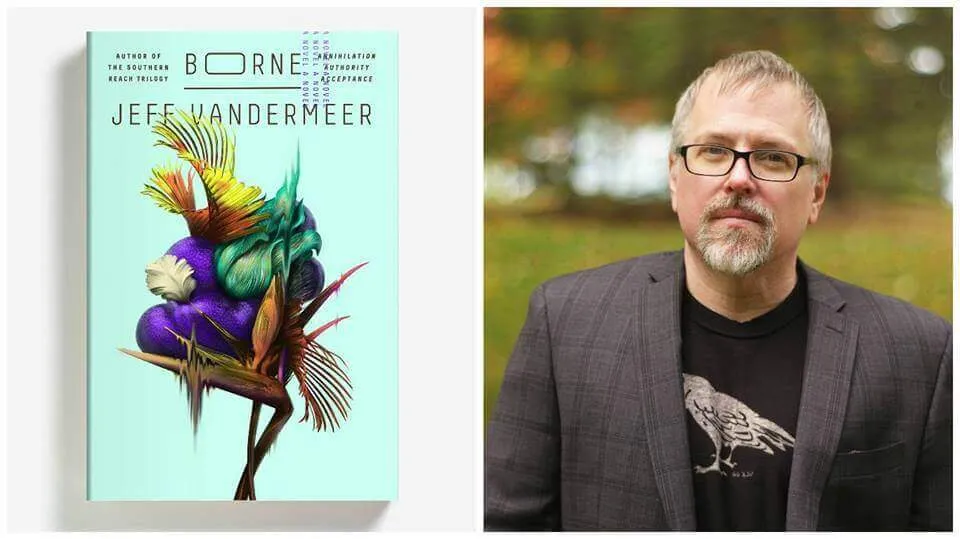

With influences ranging from Kafka to anime to his current home state of Florida, speculative fiction author Jeff Vandermeer’s works offer a unique blend of dark science fiction with hints of fantasy and something else, something weird—or more accurately, New Weird, a literary movement that challenges many of speculative fiction’s established tropes.

Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, starting with Annihilation, earned the Nebula Award and the Shirley Jackson Award. It was adapted for the big screen by Alex Garland, director of Ex Machina. Vandermeer’s followup to the Southern Reach series, Borne, released with rave reviews and hit the New York Times bestsellers list (among others).

When I discovered that Vandermeer would be keynoting at Writers Digest Conference, I couldn’t resist asking for an interview while we were both in New York City for the event. His wife, Ann Vandermeer—a speculative fiction legend in her own right, with a number of awards for her work including a Hugo—also presented at the conference.

If that’s not busy enough for one weekend, the couple was also taking advantage of the trip to hunt for furniture for their new home.

All the same, they kindly carved out a little time to talk.

Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, starting with Annihilation, earned the Nebula Award and the Shirley Jackson Award. It was adapted for the big screen by Alex Garland, director of Ex Machina. Vandermeer’s followup to the Southern Reach series, Borne, released with rave reviews and hit the New York Times bestsellers list (among others).

When I discovered that Vandermeer would be keynoting at Writers Digest Conference, I couldn’t resist asking for an interview while we were both in New York City for the event. His wife, Ann Vandermeer—a speculative fiction legend in her own right, with a number of awards for her work including a Hugo—also presented at the conference.

If that’s not busy enough for one weekend, the couple was also taking advantage of the trip to hunt for furniture for their new home.

All the same, they kindly carved out a little time to talk.

JV: I think that, well…weird fiction basically is something that was defined by Lovecraft, but basically, I think, existed before that, and has another thread, which is the Kafka-esque. And basically the idea is that unlike certain types of horror, the emphasis is not on the terror or the horror, the emphasis is on this beautiful unknown thing that may be monstrous but that isn’t automatically considered deadly or horrific, that may be even just by the narrator.

The idea is also to divest oneself of tropes that already come with so many associations that when you write about them, those associations come in. Like vampires—so a vampire story, in general, cannot be considered a weird story because it is not an unknown. It is a known that you are kind of repurposing or renovating.

And then New Weird is just simply that around the early part of this century there was a conversation being had, mostly by British writers, around the work of China Mieville and M. John Harrison, as to what do we call this impulse which seems to have new wave influences seems to incorporate things like Clive Barker’s body horror but is often set in secondary fantasy worlds.

What is this movement? You know, it’s partially genre, it’s partially whatever, and someone put forth the term New Weird. And it was a question, and it was a discussion, that has since solidified into a movement that some people don’t think exists. But it keeps welling up whenever one of us who was involved in the initial conversation has a book that hits big or something. And then suddenly, for example, with Annihilation suddenly I’m New Weird again, as opposed to just a writer or a Weird writer.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. I mean, New Weird is kind of a category, but it’s also led, in some places like in Eastern Europe, to editors being able to do whole marketing schemes. They call it New Weird and publish stuff that is deeply strange that they couldn’t otherwise publish. And so it’s had a very interesting effect. But it always makes me chuckle because it means so much and so little to so many people.

What is this movement? You know, it’s partially genre, it’s partially whatever, and someone put forth the term New Weird. And it was a question, and it was a discussion, that has since solidified into a movement that some people don’t think exists. But it keeps welling up whenever one of us who was involved in the initial conversation has a book that hits big or something. And then suddenly, for example, with Annihilation suddenly I’m New Weird again, as opposed to just a writer or a Weird writer.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. I mean, New Weird is kind of a category, but it’s also led, in some places like in Eastern Europe, to editors being able to do whole marketing schemes. They call it New Weird and publish stuff that is deeply strange that they couldn’t otherwise publish. And so it’s had a very interesting effect. But it always makes me chuckle because it means so much and so little to so many people.

For me, I like it as a descriptor, if I have to be described as anything, simply because it is hard to turn into a marketing term or category in a bookstore. And what I hate about the discussions about speculative fiction in particular are that they often become discussions about marketing, and not the art and craft of it, because of the fact that there is that tradition of the pulps and everything, and things coming from that commercial impulse.

So when you have something like Weird, I don’t mind being called that because it’s hard in the first place to define what that is, and I like that. I don’t really like being pinned down because I do like to write a lot of different things.

For me, I like it as a descriptor, if I have to be described as anything, simply because it is hard to turn into a marketing term or category in a bookstore. And what I hate about the discussions about speculative fiction in particular are that they often become discussions about marketing, and not the art and craft of it, because of the fact that there is that tradition of the pulps and everything, and things coming from that commercial impulse.

So when you have something like Weird, I don’t mind being called that because it’s hard in the first place to define what that is, and I like that. I don’t really like being pinned down because I do like to write a lot of different things.

JV: No, I don’t think there was any real crossover at all. Mostly because—and I don’t remember the timing of it—but I remember having a long conversation with Alex Garland where, because I had written the predecessory timeline novella, I had written the Predator novel, and I was very happy in both cases that there was no creative oversight—they let me do exactly what I wanted, and they didn’t change anything.

So, in that context, and then also, the fact that I’ve been lucky to have so much fan art, which I really encourage, I told Alex Garland you know, it’s fine if you make changes to the plot, if your entry point is different.

I think in retrospect I still would have preferred—you know, obviously, there are a lot of things about the movie I would have preferred be more faithful to the book.

And it’s also true to say that I didn’t envision certain kind of changes happening, I was mostly talking about story.

But I was fairly much removed from the movie, and in part because I was so involved in writing the novels then, too. And also because fairly early on I recognized that Garland was an auteur, in the sense that he has a vision and he’s just going to do it, and there’s not a lot that you can say. And that’s fine, if that’s your process, but it didn’t seem worth my time to work against that.

JV: Yeah, I deliberately wanted to blur the distinction between fantasy and science fiction, in part because the whole third part of the book becomes a quest in the fantasy traditional sense. But also because I think biotech is…dealing with it as hard science fiction is a huge mistake, because the way it’s going to permeate our lives is not going to be that way. It’s going to be in a more organic and synergistic way.

And I made the comparison that just because—I mean, you wouldn’t, in a contemporary realism novel, want to read six pages about how a smartphone works, right? And I feel like the blending of science fiction and fantasy is a way for me to get past that point about biotech.

And I think a huge tell is that a writer who is writing something about the future, about biotech, any kind of additional explanation is a tell that they’re not really writing from the point of view of a character from the future. They’re just writing from the point of view of a writer who can’t conceptualize what a person in the future, how they would interact with it. So the easiest way to do it was to blur it and have it be more fantastical.

I’m also really influenced by anime—by Miyazaki, by Mobius. And all of comic history…there is an equivalent of a giant flying bear, and no one cares what the explanation is. They just go along with it because the visual is compelling. And though I do have an explanation, that was part of the impulse was that, you can get away with such things, you can move past such explanations to something more interesting if you write it the right way.

And I’ll give a good example—In Finch, an earlier novel, I was trying to subvert noir stereotypes, and so I have this femme fatale character as a girlfriend, and I was trying to flip that by the end. It requires some patience, because it means that the reader has to, first of all, sense I’m doing that, and this isn’t going to be the usual thing.

But then, when I actually got to the point where I was trying to then make that character have their own story, I found that the constraint was actually making it impossible for me to think past that. And so at that point, I sent it out to several first readers who were women and said, “Look, I know I’m doing a crap job with this character, what is the problem?”

And immediately it was so simple. It was just like, “This is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong,” and it was just following what they said and giving them the thanks in the acknowledgement was enough to do it.

But it was quite telling to me that just working within a construct that typically is, or has been until recently, more male-oriented, was enough to also make it more difficult to write that. So that is just one example of focusing on the person, and then consciously trying to make sure it’s correct in some way.

I don’t know if that’s a good answer or not, but I don’t actually know how I do any of that, I just inhabit a character very deeply and just see where it goes.

It probably did help that just about every mentor I had growing up was a woman who was a poet or a writer. That probably helped knock some of the stupid out of the stuff? I don’t know.

And I’ll give a good example—In Finch, an earlier novel, I was trying to subvert noir stereotypes, and so I have this femme fatale character as a girlfriend, and I was trying to flip that by the end. It requires some patience, because it means that the reader has to, first of all, sense I’m doing that, and this isn’t going to be the usual thing.

But then, when I actually got to the point where I was trying to then make that character have their own story, I found that the constraint was actually making it impossible for me to think past that. And so at that point, I sent it out to several first readers who were women and said, “Look, I know I’m doing a crap job with this character, what is the problem?”

And immediately it was so simple. It was just like, “This is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong,” and it was just following what they said and giving them the thanks in the acknowledgement was enough to do it.

But it was quite telling to me that just working within a construct that typically is, or has been until recently, more male-oriented, was enough to also make it more difficult to write that. So that is just one example of focusing on the person, and then consciously trying to make sure it’s correct in some way.

I don’t know if that’s a good answer or not, but I don’t actually know how I do any of that, I just inhabit a character very deeply and just see where it goes.

It probably did help that just about every mentor I had growing up was a woman who was a poet or a writer. That probably helped knock some of the stupid out of the stuff? I don’t know.

Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, starting with Annihilation, earned the Nebula Award and the Shirley Jackson Award. It was adapted for the big screen by Alex Garland, director of Ex Machina. Vandermeer’s followup to the Southern Reach series, Borne, released with rave reviews and hit the New York Times bestsellers list (among others).

When I discovered that Vandermeer would be keynoting at Writers Digest Conference, I couldn’t resist asking for an interview while we were both in New York City for the event. His wife, Ann Vandermeer—a speculative fiction legend in her own right, with a number of awards for her work including a Hugo—also presented at the conference.

If that’s not busy enough for one weekend, the couple was also taking advantage of the trip to hunt for furniture for their new home.

All the same, they kindly carved out a little time to talk.

Vandermeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, starting with Annihilation, earned the Nebula Award and the Shirley Jackson Award. It was adapted for the big screen by Alex Garland, director of Ex Machina. Vandermeer’s followup to the Southern Reach series, Borne, released with rave reviews and hit the New York Times bestsellers list (among others).

When I discovered that Vandermeer would be keynoting at Writers Digest Conference, I couldn’t resist asking for an interview while we were both in New York City for the event. His wife, Ann Vandermeer—a speculative fiction legend in her own right, with a number of awards for her work including a Hugo—also presented at the conference.

If that’s not busy enough for one weekend, the couple was also taking advantage of the trip to hunt for furniture for their new home.

All the same, they kindly carved out a little time to talk.

EW: To start out I want to talk about what Weird fiction is, and also New Weird is a term I’ve been seeing. Is that a different movement? Is it a sub-genre?

EW: To start out I want to talk about what Weird fiction is, and also New Weird is a term I’ve been seeing. Is that a different movement? Is it a sub-genre?

JV: I think that, well…weird fiction basically is something that was defined by Lovecraft, but basically, I think, existed before that, and has another thread, which is the Kafka-esque. And basically the idea is that unlike certain types of horror, the emphasis is not on the terror or the horror, the emphasis is on this beautiful unknown thing that may be monstrous but that isn’t automatically considered deadly or horrific, that may be even just by the narrator.

The idea is also to divest oneself of tropes that already come with so many associations that when you write about them, those associations come in. Like vampires—so a vampire story, in general, cannot be considered a weird story because it is not an unknown. It is a known that you are kind of repurposing or renovating.

And then New Weird is just simply that around the early part of this century there was a conversation being had, mostly by British writers, around the work of China Mieville and M. John Harrison, as to what do we call this impulse which seems to have new wave influences seems to incorporate things like Clive Barker’s body horror but is often set in secondary fantasy worlds.

What is this movement? You know, it’s partially genre, it’s partially whatever, and someone put forth the term New Weird. And it was a question, and it was a discussion, that has since solidified into a movement that some people don’t think exists. But it keeps welling up whenever one of us who was involved in the initial conversation has a book that hits big or something. And then suddenly, for example, with Annihilation suddenly I’m New Weird again, as opposed to just a writer or a Weird writer.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. I mean, New Weird is kind of a category, but it’s also led, in some places like in Eastern Europe, to editors being able to do whole marketing schemes. They call it New Weird and publish stuff that is deeply strange that they couldn’t otherwise publish. And so it’s had a very interesting effect. But it always makes me chuckle because it means so much and so little to so many people.

What is this movement? You know, it’s partially genre, it’s partially whatever, and someone put forth the term New Weird. And it was a question, and it was a discussion, that has since solidified into a movement that some people don’t think exists. But it keeps welling up whenever one of us who was involved in the initial conversation has a book that hits big or something. And then suddenly, for example, with Annihilation suddenly I’m New Weird again, as opposed to just a writer or a Weird writer.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. I mean, New Weird is kind of a category, but it’s also led, in some places like in Eastern Europe, to editors being able to do whole marketing schemes. They call it New Weird and publish stuff that is deeply strange that they couldn’t otherwise publish. And so it’s had a very interesting effect. But it always makes me chuckle because it means so much and so little to so many people.

EW: How do you go about writing Weird? Is this something that chooses you with the story, or do you choose it and deliberately chase after it?

JV: I think there are writers who are just passing through, who are agile enough that they change their style or voice depending on the nature of the story, and they write some pieces of Weird fiction but they also write other stuff. I think for a lot of what you might call Weird writers, especially historically—and in doing the research for The Weird anthology, I’d say this is true—they tended to be outsider artists, they tended to basically be living the thing they were writing about; even if it was strange and uncanny, they were in some senses seeing the world in an uncanny way. For me, I like it as a descriptor, if I have to be described as anything, simply because it is hard to turn into a marketing term or category in a bookstore. And what I hate about the discussions about speculative fiction in particular are that they often become discussions about marketing, and not the art and craft of it, because of the fact that there is that tradition of the pulps and everything, and things coming from that commercial impulse.

So when you have something like Weird, I don’t mind being called that because it’s hard in the first place to define what that is, and I like that. I don’t really like being pinned down because I do like to write a lot of different things.

For me, I like it as a descriptor, if I have to be described as anything, simply because it is hard to turn into a marketing term or category in a bookstore. And what I hate about the discussions about speculative fiction in particular are that they often become discussions about marketing, and not the art and craft of it, because of the fact that there is that tradition of the pulps and everything, and things coming from that commercial impulse.

So when you have something like Weird, I don’t mind being called that because it’s hard in the first place to define what that is, and I like that. I don’t really like being pinned down because I do like to write a lot of different things.

EW: With the Southern Reach trilogy, you wrote all three of these novels in one year?

JV: Not really. I wrote one novel that was, [and] the idea for the whole trilogy was bought after I did that. Then I had about two years to write the other novels, but I spent most of one year thinking about them, and then wrote the second two in one year. The distinction is important just because I had a day job since 2007, so I hadn’t really written a whole lot of novels—I had written one novel, basically, where I had all the time in the world to write it, and had never been under deadline for something where I was writing full time. So prior novels I wrote at lunch, after dinner, things like that. And so I didn’t actually know what my process was. And it turns out that if I think about a novel for about a year, and then have a year to write two novels set in the same year with the same characters, basically, it’s not that big a deal. I’m not saying it wasn’t hard, but what I’m saying is that it didn’t warp what I wanted to do with the books, if that makes any sense. Sometimes I feel weird about talking about the process because people think, “oh well you wrote them so quickly,” but they’re exactly the way that I wanted them to be.EW: Did you learn any new tricks about making your process more efficient by doing that?

JV: I’m not a big fan of efficiency when it comes to creative writing. But I would say that I did have to compress certain things. Which is to say that, usually, you set a manuscript aside, you wouldn’t look at it for three months, and I didn’t have that option, So I had to find ways to trick myself into having perspective on something, to be able to come back to it with fresh eyes. I had to also—I was a real stickler for every detail of the setting being from first-hand knowledge. I didn’t want anything to be second-hand, and so a lot of my experience in Florida working as a software contractor going around to like county health departments helped a lot getting the weird bureaucracy of the Southern Reach down. And then I say in a lot of interviews, I broke into my own house for a scene because we needed to break into a house where the former director lived in and the current director was breaking into that house and I couldn’t visualize it, so those are the actual motions of breaking into my own house and recording my own house as her house. And that worked perfectly to get all the sensory details for that. So it was doing a lot of what I would call method acting, which is something I hadn’t done before. So for Control, who is paranoid in the second book, I had to get in that mindset for months at a time, to the point where I’m in my car…and there’s a mosquito smashed to the inside window that I don’t remember smashing. And so my paranoid thought as Control was that someone was in my car, searching my car, and happened to smash a mosquito while they were in here. Which is a minor thing you wouldn’t usually put in a novel, but for Control and for the novel, it worked perfectly. So as soon as I got out of the car, I added that to one of the scenes that I was working on. And so it added these little moments of authenticity because I was actually living in the character. And I really highly recommend researching what I would call drama techniques, things that actors do, and applying them to writing. I am also experimenting with looking at conceptual art projects and other art projects and thinking what is their translation into fiction? And I think that also helps create, to get somewhere new. EW: The creative collaboration between creating the movie for the first book while also writing the second and the third books—was there any creative synergy that came out of that, that affected how the second and third book developed? Or did you already have it all?

EW: The creative collaboration between creating the movie for the first book while also writing the second and the third books—was there any creative synergy that came out of that, that affected how the second and third book developed? Or did you already have it all?

JV: No, I don’t think there was any real crossover at all. Mostly because—and I don’t remember the timing of it—but I remember having a long conversation with Alex Garland where, because I had written the predecessory timeline novella, I had written the Predator novel, and I was very happy in both cases that there was no creative oversight—they let me do exactly what I wanted, and they didn’t change anything.

So, in that context, and then also, the fact that I’ve been lucky to have so much fan art, which I really encourage, I told Alex Garland you know, it’s fine if you make changes to the plot, if your entry point is different.

I think in retrospect I still would have preferred—you know, obviously, there are a lot of things about the movie I would have preferred be more faithful to the book.

And it’s also true to say that I didn’t envision certain kind of changes happening, I was mostly talking about story.

But I was fairly much removed from the movie, and in part because I was so involved in writing the novels then, too. And also because fairly early on I recognized that Garland was an auteur, in the sense that he has a vision and he’s just going to do it, and there’s not a lot that you can say. And that’s fine, if that’s your process, but it didn’t seem worth my time to work against that.

EW: Particularly with Borne, there seems to be a lot of blending of different genre tropes from science fiction and also fantasy—and specifically between the Company and Mord, and then the Magician, who are nemeses, the genres are almost pitted against each other, and I thought that was really cool. Is that something you were seeking to play with?

EW: Particularly with Borne, there seems to be a lot of blending of different genre tropes from science fiction and also fantasy—and specifically between the Company and Mord, and then the Magician, who are nemeses, the genres are almost pitted against each other, and I thought that was really cool. Is that something you were seeking to play with?

JV: Yeah, I deliberately wanted to blur the distinction between fantasy and science fiction, in part because the whole third part of the book becomes a quest in the fantasy traditional sense. But also because I think biotech is…dealing with it as hard science fiction is a huge mistake, because the way it’s going to permeate our lives is not going to be that way. It’s going to be in a more organic and synergistic way.

And I made the comparison that just because—I mean, you wouldn’t, in a contemporary realism novel, want to read six pages about how a smartphone works, right? And I feel like the blending of science fiction and fantasy is a way for me to get past that point about biotech.

And I think a huge tell is that a writer who is writing something about the future, about biotech, any kind of additional explanation is a tell that they’re not really writing from the point of view of a character from the future. They’re just writing from the point of view of a writer who can’t conceptualize what a person in the future, how they would interact with it. So the easiest way to do it was to blur it and have it be more fantastical.

I’m also really influenced by anime—by Miyazaki, by Mobius. And all of comic history…there is an equivalent of a giant flying bear, and no one cares what the explanation is. They just go along with it because the visual is compelling. And though I do have an explanation, that was part of the impulse was that, you can get away with such things, you can move past such explanations to something more interesting if you write it the right way.

EW: A few months ago, there was a Twitterstorm about men and how they are writing women characters. But I think one of the things that is really striking about the Southern Reach series and Borne is how dynamic and complicated the women characters are, and even contrary to a lot of the stereotypes. So where do you think some of those lines should be?

JV: I always try to focus on the specific person I am writing about, for one thing. I always try to make sure that that person is a combination of people I know to some degree, or observe, or know about; something from my imagination; and something that is personal to me. And then I just try to be true to what I think they would do how I think they would act. But there are certain things I think I have done consciously—like once I made a conscious decision not to have physical descriptions of the women in Annihilation, it served the narrative because that sort of subsumes them in the landscape more, but it was also making a point, and the point was that male authors tend to be crap at writing descriptions of women in novels. And I also wanted to make the point that you have to decide what you think of these women based on what they say and what they do, not what they look like. At the same time, I thought it was really valuable at the beginning of the second book to give you a better sense of who they were, and kind of shatter any kind of stereotypical images that may have built up anyway. And it was quite fascinating to me, in some cases, how some readers, even though that information is there in the second book, just read over it, just edited it out, like “I’m not going to let that get in the way of my actual mental image of them.” So it’s been really interesting. I think one thing too is that male writers get into real trouble when they think it’s really a good idea to lay down some rules on how to write women characters. I’ll always find that really a fascinating impulse. Or to not take feedback from, well, women when writing their books. And I’ll give a good example—In Finch, an earlier novel, I was trying to subvert noir stereotypes, and so I have this femme fatale character as a girlfriend, and I was trying to flip that by the end. It requires some patience, because it means that the reader has to, first of all, sense I’m doing that, and this isn’t going to be the usual thing.

But then, when I actually got to the point where I was trying to then make that character have their own story, I found that the constraint was actually making it impossible for me to think past that. And so at that point, I sent it out to several first readers who were women and said, “Look, I know I’m doing a crap job with this character, what is the problem?”

And immediately it was so simple. It was just like, “This is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong,” and it was just following what they said and giving them the thanks in the acknowledgement was enough to do it.

But it was quite telling to me that just working within a construct that typically is, or has been until recently, more male-oriented, was enough to also make it more difficult to write that. So that is just one example of focusing on the person, and then consciously trying to make sure it’s correct in some way.

I don’t know if that’s a good answer or not, but I don’t actually know how I do any of that, I just inhabit a character very deeply and just see where it goes.

It probably did help that just about every mentor I had growing up was a woman who was a poet or a writer. That probably helped knock some of the stupid out of the stuff? I don’t know.

And I’ll give a good example—In Finch, an earlier novel, I was trying to subvert noir stereotypes, and so I have this femme fatale character as a girlfriend, and I was trying to flip that by the end. It requires some patience, because it means that the reader has to, first of all, sense I’m doing that, and this isn’t going to be the usual thing.

But then, when I actually got to the point where I was trying to then make that character have their own story, I found that the constraint was actually making it impossible for me to think past that. And so at that point, I sent it out to several first readers who were women and said, “Look, I know I’m doing a crap job with this character, what is the problem?”

And immediately it was so simple. It was just like, “This is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong, this is what you’re doing wrong,” and it was just following what they said and giving them the thanks in the acknowledgement was enough to do it.

But it was quite telling to me that just working within a construct that typically is, or has been until recently, more male-oriented, was enough to also make it more difficult to write that. So that is just one example of focusing on the person, and then consciously trying to make sure it’s correct in some way.

I don’t know if that’s a good answer or not, but I don’t actually know how I do any of that, I just inhabit a character very deeply and just see where it goes.

It probably did help that just about every mentor I had growing up was a woman who was a poet or a writer. That probably helped knock some of the stupid out of the stuff? I don’t know.

EW: To start out I want to talk about what Weird fiction is, and also New Weird is a term I’ve been seeing. Is that a different movement? Is it a sub-genre?

EW: To start out I want to talk about what Weird fiction is, and also New Weird is a term I’ve been seeing. Is that a different movement? Is it a sub-genre? EW: The creative collaboration between creating the movie for the first book while also writing the second and the third books—was there any creative synergy that came out of that, that affected how the second and third book developed? Or did you already have it all?

EW: The creative collaboration between creating the movie for the first book while also writing the second and the third books—was there any creative synergy that came out of that, that affected how the second and third book developed? Or did you already have it all? EW: Particularly with Borne, there seems to be a lot of blending of different genre tropes from science fiction and also fantasy—and specifically between the Company and Mord, and then the Magician, who are nemeses, the genres are almost pitted against each other, and I thought that was really cool. Is that something you were seeking to play with?

EW: Particularly with Borne, there seems to be a lot of blending of different genre tropes from science fiction and also fantasy—and specifically between the Company and Mord, and then the Magician, who are nemeses, the genres are almost pitted against each other, and I thought that was really cool. Is that something you were seeking to play with?