A Guide to Japanese Poetry Forms

We’ve all heard of haiku, but that’s far from the only Japanese poetry form. On the contrary, it’s only one in a long line of poetic forms that predate many English forms of poetry. Japanese poetry forms, in particular, have always fascinated me not only for its brevity but for a different approach to content. While this isn’t a comprehensive text, this guide to Japanese poetry forms is a good place to start.

Waka

The earliest Japanese poetry has its roots in Chinese poetry and the Chinese language. While the earliest Japanese poems written in Chinese were called kanshi, the first Japanese poems written in Japanese were called waka. Waka are less a form than a broad term for classical Japanese poetry.

| Form Name | Meaning of the Form Name | Lines and Syllables |

| Bussokusekika | Buddha Footprint Poem | Six lines 5/7/5/7/7/7 |

| Choka | Long Poem | Nine lines 5/7/5/7/5/7/5/7/7 |

| Katauta | Half Poem, Poem Fragment | Three lines 5/7/7 |

| Sedoka | Head-repeated Poem, Memorized Poem | Six lines 5/7/7/5/7/7 |

| Tanka | Short Poem | Five lines 5/7/5/7/7 |

These classic Japanese poetry forms are still in use today, not only by Japanese poets, but poets around the world. In Victoria Chang’s recent book, OBIT, she largely used poems shaped like obituaries to mourn her parents. Interspersed in these mournful pages were small poems about her children, all of which were in the tanka form.

Renga

Of all the classic, waka poetry forms, tanka were the most popular. They were so popular, in fact, that poets started using them to communicate. One poet would write the first three lines, and then another poet would complete the six-line stanza. Six lines wasn’t enough to foster a conversation, however, and so the renga was born.

Renga use the tanka form of 5/7/5/7/7, but use that as a stanza. A renga must have at least 100 stanzas. Between the 12th and 15th centuries, renga were a favorite pastime not only of Japanese poets, but everyone in Japan from aristocrats on down. Renga were initially based on light, comic topics. As time went on and the form stayed popular, however, more serious renga were written. Thus a distinction between mushin (comic) and ushin (serious) renga was drawn.

Haiku

Look again at the tanka or renga form. Pay close attention to those first three lines. Five syllables, seven syllable, five syllables. Sound familiar? Spinning out of the 100-stanza renga and six-line tanka was the most famous Japanese poetry form: haiku. Even at a fairly young age, I remember English teachers assigning the haiku form because of the small size and lack of rhyme. The form consists of three lines: five syllables, seven syllables, and five syllables. Only 17 total syllable. Simple, yes?

Well, maybe not so simple. Haiku generally focus on nature. With so few syllables available, every image needs to pack as much punch as possible. Rather than simply describing a pastoral setting, haiku seek to explore nature as a metaphor for emotion and the emotions evokes by nature.

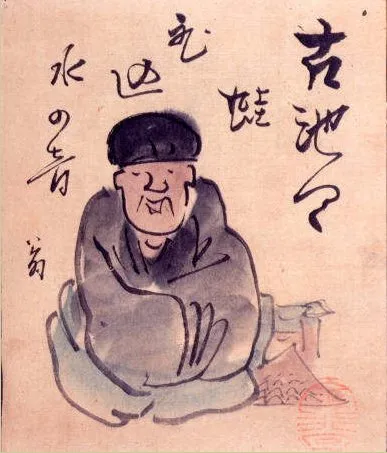

One of the most famous haiku is by Matsuo Bashō, titled “The Old Pond,” which can be found in Basho: The Complete Haiku.

Despite its popularity, haiku is actually a newer Japanese poetry form. It started to be written in the 17th century, and the term haiku only came into use in the 19th century. Karai Senryu created a variation (the Senryu, named after him) that changed its focus from nature and emotion to human foibles and the irony of life. These variants are often far less serious and more satirical than their older cousin. Haiku was popularized in English in the early 20th century by the imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, H.D., and T.E. Hulme.

Haiga

Haiga is not actually a form of poetry, but rather a different way of delivering that poetry. Japan, like China, has a storied history with calligraphy. Not only are the words important, but way in which these words are placed upon a page can be things of beauty and art.

As early as the 7th century in China and the 17th century in Japan, poems were laid over a painting using calligraphy. During Japan’s Edo period, the haiku and senryu forms became the chosen forms for this particular artistic treatment, and so the haiga was born. Haiga were frequently painted on wood blocks, cloth, or paper, and used as room decorations.

In Zen Buddhism, creating a haiga is one way of meditating, focusing on the words of the poem, the pastoral painted image, and the calligraphy all at once. In modern day, haiga seems to have found a twisted home with Instagram. Just search for poetry to find hundreds of images with stanzas floating in front of them. Okay, maybe that’s pushing the form too much.

Now grab some paper and a pencil and write yourself a haiku. Give the tanka a spin. While you’re at it, remember to make your haiku a metaphor for nature and the your inner emotional landscape. Write a tanka about your kids (or somebody else’s kids) like Victoria Chang. Embrace these wonderful Japanese poetry forms and all the depths they contain.