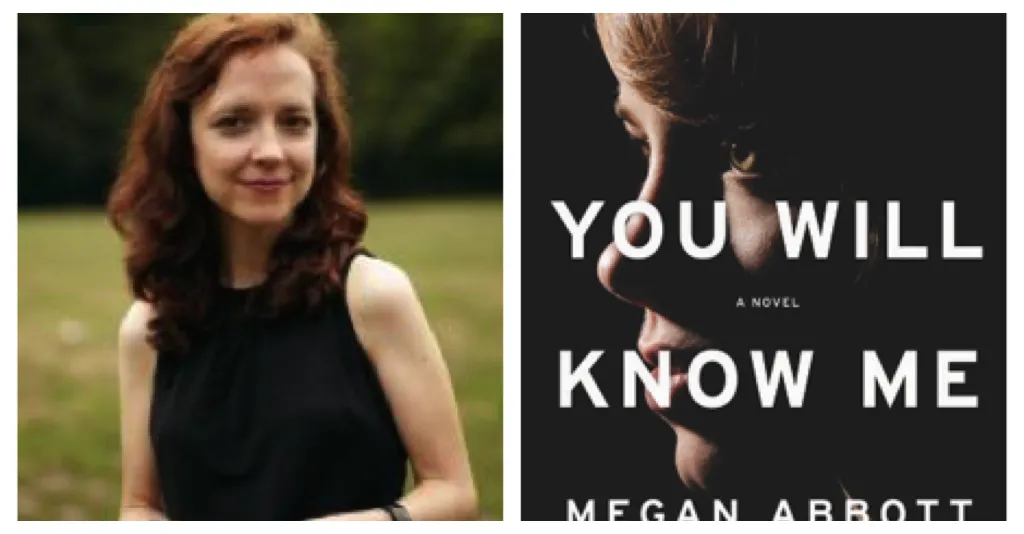

“Girlhood as a kind of freedom, womanhood as a kind of burden”: An Interview with Megan Abbott

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Acclaimed thrill writer Megan Abbott’s You Will Know Me hits shelves right as Olympics season gears up. These two things may not appear to have anything in common, but the novel follows a gymnastics prodigy whose family puts everything on the line to help their daughter succeed.

Abbott’s novel is far more than a story about an elite gymnast. It’s a book that explores girlhood, secrets, ambition, and the ways that a family works when a prodigy is among them. The themes in this book traverse some of the same territory she’s tread in previous thrillers, as well as in her earlier noir titles, but she does so in a way that continues to be fresh, exciting, and absolutely worth delving into.

But rather than expand upon why this book, as well as Abbott’s previous titles, are worth reading, here’s a chat with the author herself about why she writes what she does, why girlhood is such a fascinating topic in literature, female friendship, feminism, and so much more.

Oh, and we talk about the differences between adult fiction and young adult fiction, as well as some of Abbott’s favorite teen reads. Light and easy stuff, y’all!

You Will Know Me is your latest release and it follows an Olympic hopeful gymnast. On the surface, it’s a story about ambition and the sacrifices a family will make to ensure success. Let’s start with the basics: what inspired the story?

I’ve always been fascinated by the families of prodigies. How power works, and ambition. How, or if, one can separate the child’s drive from the parents’. Then, during the London Olympics in 2012, I saw this viral video of the parents of American gymnast Aly Raisman watching their daughter’s routine and it kind of blew me away. They were so invested in it, so connected to her. They moved as she moved. They knew every beat of the performance. The online response to it was all over the place. Some people found it funny, others found it problematic, or worse. There’s never a simple answer to how invested parents should be in their children’s development, but with exceptionally talented children, these questions become trickier. Before long, the story was just unfurling for me and I started writing.

But this isn’t a book about superficiality. It’s about the things that lie in the shadows. You mine ambition and madness, both on the part of Devon, the Olympic hopeful, as well as her parents and her coaches. What draws you toward writing about these two meaty topics in a way that connects them to one another and yet also distances them from each other?

Thank you so much. And my difficulty in framing an answer tells you how intertwined they feel to me. I do think female ambition is viewed by the culture at large. It’s hard not to think about it all the time in this election year. So that tension—especially as a female writer with my own ambitions—fascinates me. It seems like ambition for the sake of female achievement—whether it’s the female herself or her family or significant other—is far more frequently treated as excessive, threatening, even pathological. Women are still, in general, taught to mask their drives, their desires, their goals. Or to find ways to soften them, prettify them. It’s only been in recent years—in particular, in female sports—that ambition has begun to be reframed as beautiful, powerful. So a lot of this thinking—murky though it is!—found its way into the book.

While Devon’s parents are heavily involved in her gymnastics career, she maintains a very private life all her own. This sort of “second life” is a hallmark of YA fiction, in that we see the teenager’s stories from their point of view, which often lacks the involvement of their parents. You bring the parents in, both in You Will Know Me and in your previous novel, The Fever. How do you successfully offer up what it is that we see through our adult lenses and, at the same time, offer up what the truth of things is as — if not more — sharply through the eyes of a teenager?

It is so interesting, isn’t it? I don’t have kids, but my friends who do talk about that weird transition—or even moment—when you realize you have no idea what’s going on in your child’s head. It’s such an important thing when you’re growing up—to develop an inner life, a secret life. But in the case of the Knox family, I think it’s particularly freighted because they are so much more involved with each other due to their shared efforts. Growing up, I was so close to my parents and it often felt like a betrayal when I began to keep “secrets” (however harmless) from them. I think that feeling informed a lot of You Will Know Me. In especially close families, it can be so much more surprising—the secrets teens keep from parents and, by the same token, the ones parents keep from teens.

Devon’s not just inherently talented; she’s driven to be the best she can be. She is ambitious. Ambition is, of course, a trait that can be lumped into the sweet little category of what makes a female character unlikable. Between that, rage that you explore in Dare Me, and hysteria in The Fever, you’ve set up a cast of teenage girls who are emotionally complex. What makes these traits so rich and raw to explore?

I think the rawness comes from how comparatively untrod this terrain has been. American novels are in some ways defined by the male coming of age story, the male hero. Male ambition and male conquest. Male doubt and male midlife crisis. There have always been writers who told just as strident, violent and rich female stories—from the Brontës to Sylvia Plath to Charles Portis and onward—but we still have a lot of ground to make up. And in recent years, in large part because of efforts made in YA and crime fiction, we’re staking new turf at a rapid rate, and it feels good.

In your last three books, there’s been a focus on an active, engaged, and intense use of the female body. Dare Me features fiercely competitive cheerleaders; The Fever follows girls who become ill with a tic disorder; and You Will Know Me puts a powerhouse gymnast’s body into the spotlight. In these portrayals, the girls have complete control over their bodies. These aren’t the dead girls of thrillers and in fact, your books don’t feature the ever-popular “Girl” title trend. They aren’t passive, yet there’s still an outsider spotlight put upon them — from spectators to fearful parents. Can you talk a bit about the adolescent female body, why it takes on the roles it does in your stories, and what you think it means that it is such an object of fascination, of horror, and ultimately, of literary power?

This is an area I don’t think I’ll ever lose my fascination with. The female body, especially the young one, has always been a spectacle in our culture. I guess one could argue it’s about fertility, survival of the species depends on it, which makes it dangerously powerful. So when we make it object of the gaze, we exert some control over it. The body is to be looked at but never to return that look. Instead, it’s static, site of fantasy. And in my books (and I’m far from the only author doing this), I’ve tried to reverse the lens. What happens when the female body looks back? Or when the female body as subject—and a subject so powerful that not even the owner itself can always control it? In You Will Know Me, it is Devon’s gift and curse. It can turn on her at any moment. I became fixated in particular on the way some gymnasts hope to forestall puberty because it will disrupt the physics of their routines. It will weight them down. Girlhood as a kind of freedom, womanhood as a kind of burden. It’s such complicated stuff.

Female friendship has been a pretty hot topic in the last year or so. We’ve seen pieces discussing great fiction with tough female friendships, as well as pieces by writers and critics that attempt to color all female friendships as one thing. What sort of aspects do you think play a role in the most authentic and successful depictions in fiction?

I feel like I’ve read some superb books in this area just in the last few months, like Girls on Fire by Robin Wasserman, Rich and Pretty by Rumaan Alam, Under the Influence by Joyce Maynard. I think as long as the relationship is complicated, and changeable, it’s going to feel real. It isn’t always—but often is!—about power and intensity. It doesn’t always center on a deeper rivalry—but often does! Sometimes, especially in one’s early teens, it can feel like the most dramatic of romances. The thing it isn’t, I think, is some watered-down version of Sex in the City (which itself was much more clever about the prickly nature of friendships than the copycats to follow). Just like you can never know what goes on in another person’s marriage, friendships are tangled things, and that is also the source of their great beauty.

In your writing, you flirt with how complicated female relationships can be — they can sway from utterly platonic to being fiercely sensual…even somewhat sexualized. What is it that makes female relationships such a ripe area of fictional exploration–and are there any particular aspects in your mind that separate teen girls, specifically?

I will always be drawn to the intensity of teen girl duos, how they can become almost a merging of identities. I think these kinds of friendships are the ways we find ourselves, build ourselves, create ourselves. And they’re rehearsals for all the relationships to come. Whether it’s two outsiders, or two opposites, or two girls brought together my circumstance or chemistry—it’s so important to our notions of womanhood going forward. Who we’re going to be, how we’re going to choose to be treated, and to treat others. And it’s all happening during this time of firsts—these tester runs into adulthood. And now, with social media and everything it’s wrought, it’s even more complicated, more a dense thicket of feeling and intimacy. Or maybe I’m just writing about them all the time to figure out my own relationships with other women. Sometimes I still find I’m a different person with all of them.

Playing off that and the previous question, why do you tackle the sexuality of teen girls in your work? Because it’s not just about their own experiences of becoming sexual beings. You delve into the ways the world puts expectations of their sexual awakening (and purity and socially-demanded ignorance) upon them.

I think we’re still deeply frightened, as a culture, of teen girl desire—and female desire in general. My book The End of Everything is the one that still tends to elicit upset responses from readers. The notion that a thirteen-year-old girl might long for the father of a friend was so disturbing to so many readers—in part, because they’re viewing it from cautious adult eyes. But when you’re thirteen, you’re just feeling what you’re feeling. When young teen boys express desire for adult women, it’s routine, or funny. But when girls do…

Madness — or perhaps it could be labeled hysteria – is an undercurrent in your contemporary thrillers, from the way that girls aren’t allowed to be ambitious and become powderkegs because of it, to the ways that parents will go all out in order to protect the purity of their girls. This begs the question: in what ways does madness stem from social expectations and in what ways is it simply part of being an adolescent hormonal cocktail?

I admit, in my books, at least, I don’t consider it madness at all! “Madness,” like “hysteria,” often becomes a word we use to diminish or control or separate ourselves from that which we find uncomfortable, troubling. I think, in some ways, desire or anger or any of the primal feelings can make us feel crazy, they unsettle us, especially when those feelings come from a young woman. We want to make a joke of it, or dismiss it, or contain or stigmatize it because it makes us so uncomfortable. And that strenuous effort—isn’t that, by some measure, the real “madness”?

Your work, especially your teen-centered novels of late, have tremendous teen appeal but are packaged for adult readers. Where do you think the line between adult fiction and YA fiction falls? What makes your work adult fiction, rather than YA fiction?

Boy, I have no idea! I suppose I think of them as adult fiction because adult characters are so central in all them, including adult POVs. But I’m not sure where one draws the line or if one should. I don’t really understand the notion that adults shouldn’t read books about teenagers and vice versa. We read what we connect to, right?

Everyone loves to ask if an author’s work is feminist, and it’s a question that’s been asked of you in plenty of previous interviews (to which you’ve answered you don’t write with a message in mind — a perfect response!). But rather than ask that, what I’d like to know is this: what do you think makes a work of fiction feminist?

I should clarify that I definitely am a feminist, but if I approached writing a novel with a specific agenda, I’d be afraid the story and characters wouldn’t be organic. That said, I think my view of the world, of equality, of sexual violence and the burden of sexual and gender stereotypes, is still present in my books. I think if you refuse to accept traditional, oppressive ideas of female characters or male ones, if you refuse to force your characters into rigid structures or stereotypes or make them be role models, if you instead let them behave messily, think bad thoughts, do what they want…well, that’s what I want in a book. And, to me, that’s what makes a book feminist.

The idea readers need to come away with a message from a book is off-putting and reductive of the reading experience. That said, knowing how much of your fiction is centered on teen girls, it’s impossible not to wonder: what do you hope teen girls who read your work take away from it? What about adults? What, if anything, makes the hopeful takeaways differ?

Ultimately, I want the reader, any reader, to enjoy the book. To connect to the characters. I love hearing that, say, an adult male reader identified with, say, Addy in Dare Me (which I’ve heard a surprising amount). And I’ve loved hearing teen readers say they thought about their parents differently after reading Tom’s (the dad’s) perspective in The Fever. If an adult reader thinks more expansively about teenage girls after reading the book, or if a teen reader thinks one of the books speaks to her experience, I’m thrilled.

What is some of your favorite teen fiction? I’d love to know three of your favorite reads when you were a teenager and three YA novels you’ve read and loved as an adult.

Growing up, I adored S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, which I read over and over again, Judy Blume’s Deenie and all the Lois Duncan teen suspense novels, but if I had to pick one, I’ll go with Daughters of Eve. In the last few years, my favorites are E. Lockhar’s We Were Liars, and I know it’s a cliché, but I did love Hunger Games. And I just re-read all my beloved V.C. Andrews novels and the one that looms largest for me now is My Sweet Audrina, doubtless the craziest book I’ve ever read (that’s a compliment, of course!). I’m also catching up on all the Courtney Summers and Nova Ren Suma books.

Acclaimed thrill writer Megan Abbott’s You Will Know Me hits shelves right as Olympics season gears up. These two things may not appear to have anything in common, but the novel follows a gymnastics prodigy whose family puts everything on the line to help their daughter succeed.

Abbott’s novel is far more than a story about an elite gymnast. It’s a book that explores girlhood, secrets, ambition, and the ways that a family works when a prodigy is among them. The themes in this book traverse some of the same territory she’s tread in previous thrillers, as well as in her earlier noir titles, but she does so in a way that continues to be fresh, exciting, and absolutely worth delving into.

But rather than expand upon why this book, as well as Abbott’s previous titles, are worth reading, here’s a chat with the author herself about why she writes what she does, why girlhood is such a fascinating topic in literature, female friendship, feminism, and so much more.

Oh, and we talk about the differences between adult fiction and young adult fiction, as well as some of Abbott’s favorite teen reads. Light and easy stuff, y’all!

You Will Know Me is your latest release and it follows an Olympic hopeful gymnast. On the surface, it’s a story about ambition and the sacrifices a family will make to ensure success. Let’s start with the basics: what inspired the story?

I’ve always been fascinated by the families of prodigies. How power works, and ambition. How, or if, one can separate the child’s drive from the parents’. Then, during the London Olympics in 2012, I saw this viral video of the parents of American gymnast Aly Raisman watching their daughter’s routine and it kind of blew me away. They were so invested in it, so connected to her. They moved as she moved. They knew every beat of the performance. The online response to it was all over the place. Some people found it funny, others found it problematic, or worse. There’s never a simple answer to how invested parents should be in their children’s development, but with exceptionally talented children, these questions become trickier. Before long, the story was just unfurling for me and I started writing.

But this isn’t a book about superficiality. It’s about the things that lie in the shadows. You mine ambition and madness, both on the part of Devon, the Olympic hopeful, as well as her parents and her coaches. What draws you toward writing about these two meaty topics in a way that connects them to one another and yet also distances them from each other?

Thank you so much. And my difficulty in framing an answer tells you how intertwined they feel to me. I do think female ambition is viewed by the culture at large. It’s hard not to think about it all the time in this election year. So that tension—especially as a female writer with my own ambitions—fascinates me. It seems like ambition for the sake of female achievement—whether it’s the female herself or her family or significant other—is far more frequently treated as excessive, threatening, even pathological. Women are still, in general, taught to mask their drives, their desires, their goals. Or to find ways to soften them, prettify them. It’s only been in recent years—in particular, in female sports—that ambition has begun to be reframed as beautiful, powerful. So a lot of this thinking—murky though it is!—found its way into the book.

While Devon’s parents are heavily involved in her gymnastics career, she maintains a very private life all her own. This sort of “second life” is a hallmark of YA fiction, in that we see the teenager’s stories from their point of view, which often lacks the involvement of their parents. You bring the parents in, both in You Will Know Me and in your previous novel, The Fever. How do you successfully offer up what it is that we see through our adult lenses and, at the same time, offer up what the truth of things is as — if not more — sharply through the eyes of a teenager?

It is so interesting, isn’t it? I don’t have kids, but my friends who do talk about that weird transition—or even moment—when you realize you have no idea what’s going on in your child’s head. It’s such an important thing when you’re growing up—to develop an inner life, a secret life. But in the case of the Knox family, I think it’s particularly freighted because they are so much more involved with each other due to their shared efforts. Growing up, I was so close to my parents and it often felt like a betrayal when I began to keep “secrets” (however harmless) from them. I think that feeling informed a lot of You Will Know Me. In especially close families, it can be so much more surprising—the secrets teens keep from parents and, by the same token, the ones parents keep from teens.

Devon’s not just inherently talented; she’s driven to be the best she can be. She is ambitious. Ambition is, of course, a trait that can be lumped into the sweet little category of what makes a female character unlikable. Between that, rage that you explore in Dare Me, and hysteria in The Fever, you’ve set up a cast of teenage girls who are emotionally complex. What makes these traits so rich and raw to explore?

I think the rawness comes from how comparatively untrod this terrain has been. American novels are in some ways defined by the male coming of age story, the male hero. Male ambition and male conquest. Male doubt and male midlife crisis. There have always been writers who told just as strident, violent and rich female stories—from the Brontës to Sylvia Plath to Charles Portis and onward—but we still have a lot of ground to make up. And in recent years, in large part because of efforts made in YA and crime fiction, we’re staking new turf at a rapid rate, and it feels good.

In your last three books, there’s been a focus on an active, engaged, and intense use of the female body. Dare Me features fiercely competitive cheerleaders; The Fever follows girls who become ill with a tic disorder; and You Will Know Me puts a powerhouse gymnast’s body into the spotlight. In these portrayals, the girls have complete control over their bodies. These aren’t the dead girls of thrillers and in fact, your books don’t feature the ever-popular “Girl” title trend. They aren’t passive, yet there’s still an outsider spotlight put upon them — from spectators to fearful parents. Can you talk a bit about the adolescent female body, why it takes on the roles it does in your stories, and what you think it means that it is such an object of fascination, of horror, and ultimately, of literary power?

This is an area I don’t think I’ll ever lose my fascination with. The female body, especially the young one, has always been a spectacle in our culture. I guess one could argue it’s about fertility, survival of the species depends on it, which makes it dangerously powerful. So when we make it object of the gaze, we exert some control over it. The body is to be looked at but never to return that look. Instead, it’s static, site of fantasy. And in my books (and I’m far from the only author doing this), I’ve tried to reverse the lens. What happens when the female body looks back? Or when the female body as subject—and a subject so powerful that not even the owner itself can always control it? In You Will Know Me, it is Devon’s gift and curse. It can turn on her at any moment. I became fixated in particular on the way some gymnasts hope to forestall puberty because it will disrupt the physics of their routines. It will weight them down. Girlhood as a kind of freedom, womanhood as a kind of burden. It’s such complicated stuff.

Female friendship has been a pretty hot topic in the last year or so. We’ve seen pieces discussing great fiction with tough female friendships, as well as pieces by writers and critics that attempt to color all female friendships as one thing. What sort of aspects do you think play a role in the most authentic and successful depictions in fiction?

I feel like I’ve read some superb books in this area just in the last few months, like Girls on Fire by Robin Wasserman, Rich and Pretty by Rumaan Alam, Under the Influence by Joyce Maynard. I think as long as the relationship is complicated, and changeable, it’s going to feel real. It isn’t always—but often is!—about power and intensity. It doesn’t always center on a deeper rivalry—but often does! Sometimes, especially in one’s early teens, it can feel like the most dramatic of romances. The thing it isn’t, I think, is some watered-down version of Sex in the City (which itself was much more clever about the prickly nature of friendships than the copycats to follow). Just like you can never know what goes on in another person’s marriage, friendships are tangled things, and that is also the source of their great beauty.

In your writing, you flirt with how complicated female relationships can be — they can sway from utterly platonic to being fiercely sensual…even somewhat sexualized. What is it that makes female relationships such a ripe area of fictional exploration–and are there any particular aspects in your mind that separate teen girls, specifically?

I will always be drawn to the intensity of teen girl duos, how they can become almost a merging of identities. I think these kinds of friendships are the ways we find ourselves, build ourselves, create ourselves. And they’re rehearsals for all the relationships to come. Whether it’s two outsiders, or two opposites, or two girls brought together my circumstance or chemistry—it’s so important to our notions of womanhood going forward. Who we’re going to be, how we’re going to choose to be treated, and to treat others. And it’s all happening during this time of firsts—these tester runs into adulthood. And now, with social media and everything it’s wrought, it’s even more complicated, more a dense thicket of feeling and intimacy. Or maybe I’m just writing about them all the time to figure out my own relationships with other women. Sometimes I still find I’m a different person with all of them.

Playing off that and the previous question, why do you tackle the sexuality of teen girls in your work? Because it’s not just about their own experiences of becoming sexual beings. You delve into the ways the world puts expectations of their sexual awakening (and purity and socially-demanded ignorance) upon them.

I think we’re still deeply frightened, as a culture, of teen girl desire—and female desire in general. My book The End of Everything is the one that still tends to elicit upset responses from readers. The notion that a thirteen-year-old girl might long for the father of a friend was so disturbing to so many readers—in part, because they’re viewing it from cautious adult eyes. But when you’re thirteen, you’re just feeling what you’re feeling. When young teen boys express desire for adult women, it’s routine, or funny. But when girls do…

Madness — or perhaps it could be labeled hysteria – is an undercurrent in your contemporary thrillers, from the way that girls aren’t allowed to be ambitious and become powderkegs because of it, to the ways that parents will go all out in order to protect the purity of their girls. This begs the question: in what ways does madness stem from social expectations and in what ways is it simply part of being an adolescent hormonal cocktail?

I admit, in my books, at least, I don’t consider it madness at all! “Madness,” like “hysteria,” often becomes a word we use to diminish or control or separate ourselves from that which we find uncomfortable, troubling. I think, in some ways, desire or anger or any of the primal feelings can make us feel crazy, they unsettle us, especially when those feelings come from a young woman. We want to make a joke of it, or dismiss it, or contain or stigmatize it because it makes us so uncomfortable. And that strenuous effort—isn’t that, by some measure, the real “madness”?

Your work, especially your teen-centered novels of late, have tremendous teen appeal but are packaged for adult readers. Where do you think the line between adult fiction and YA fiction falls? What makes your work adult fiction, rather than YA fiction?

Boy, I have no idea! I suppose I think of them as adult fiction because adult characters are so central in all them, including adult POVs. But I’m not sure where one draws the line or if one should. I don’t really understand the notion that adults shouldn’t read books about teenagers and vice versa. We read what we connect to, right?

Everyone loves to ask if an author’s work is feminist, and it’s a question that’s been asked of you in plenty of previous interviews (to which you’ve answered you don’t write with a message in mind — a perfect response!). But rather than ask that, what I’d like to know is this: what do you think makes a work of fiction feminist?

I should clarify that I definitely am a feminist, but if I approached writing a novel with a specific agenda, I’d be afraid the story and characters wouldn’t be organic. That said, I think my view of the world, of equality, of sexual violence and the burden of sexual and gender stereotypes, is still present in my books. I think if you refuse to accept traditional, oppressive ideas of female characters or male ones, if you refuse to force your characters into rigid structures or stereotypes or make them be role models, if you instead let them behave messily, think bad thoughts, do what they want…well, that’s what I want in a book. And, to me, that’s what makes a book feminist.

The idea readers need to come away with a message from a book is off-putting and reductive of the reading experience. That said, knowing how much of your fiction is centered on teen girls, it’s impossible not to wonder: what do you hope teen girls who read your work take away from it? What about adults? What, if anything, makes the hopeful takeaways differ?

Ultimately, I want the reader, any reader, to enjoy the book. To connect to the characters. I love hearing that, say, an adult male reader identified with, say, Addy in Dare Me (which I’ve heard a surprising amount). And I’ve loved hearing teen readers say they thought about their parents differently after reading Tom’s (the dad’s) perspective in The Fever. If an adult reader thinks more expansively about teenage girls after reading the book, or if a teen reader thinks one of the books speaks to her experience, I’m thrilled.

What is some of your favorite teen fiction? I’d love to know three of your favorite reads when you were a teenager and three YA novels you’ve read and loved as an adult.

Growing up, I adored S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders, which I read over and over again, Judy Blume’s Deenie and all the Lois Duncan teen suspense novels, but if I had to pick one, I’ll go with Daughters of Eve. In the last few years, my favorites are E. Lockhar’s We Were Liars, and I know it’s a cliché, but I did love Hunger Games. And I just re-read all my beloved V.C. Andrews novels and the one that looms largest for me now is My Sweet Audrina, doubtless the craziest book I’ve ever read (that’s a compliment, of course!). I’m also catching up on all the Courtney Summers and Nova Ren Suma books.