Contemporary Native Literature: Looking Beyond the “Indian Du Jour”

This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

When a certain Native writer, who jokingly referred to himself as the “Indian du jour” for a “very long day,” admitted to sexual misconduct in 2018, the news sent shock waves through the literary world. His abominable actions compromised the lives and careers of at least ten women, some of whom were Native writers. Critics were quick to point out that this writer’s power and status stemmed from his lionization by the literary establishment. For nearly two decades, his works had been privileged and prized as the epitome of contemporary Native literature. And in response, he bought into his puffed-up role, harming many writers in the process.

The concept of the “Indian du jour,” has been a serious problem for contemporary Native literature. Tokenizing one author not only creates abusive power dynamics, but also skews the field. This longer post is a starting point for recognizing the diversity of contemporary Native literature. It is not meant to be authoritative, but rather a jumping off point for different genres, styles, and movements within present day Native writing.

In particular, N. Scott Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning House Made of Dawn changed the landscape of Native writing. Momaday’s novel influenced a younger generation of writers, providing a new aesthetic for detailing and describing facets of Native life. In the novel, the protagonist, Abel, returns to New Mexico after fighting in World War 2. Momaday explores Abel’s war trauma by showing his inability to reconnect with reservation life and ritual. Yet after leaving New Mexico, Abel also finds it impossible to cope with urban living and its social norms.

Abel’s profound sense of alienation and search for identity is a theme that carries through other Native American Renaissance–era works, such as Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, and Joy Harjo’s She Had Some Horses. Together these writers had an immense impact on the direction and popularity of Native writing.

However, the term “Native American Renaissance” is in itself problematic. As critics have pointed out, the phrase implies a dearth of Native writers and writings before the 1960s, which is simply not true. Also, many of the writers included in the Renaissance have continued working into the present day, shifting their styles and careers beyond their initial moment of fame. Despite the controversial terminology, the 1960s Renaissance marks a significant and powerful turning point in contemporary Native writing.

In particular, N. Scott Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning House Made of Dawn changed the landscape of Native writing. Momaday’s novel influenced a younger generation of writers, providing a new aesthetic for detailing and describing facets of Native life. In the novel, the protagonist, Abel, returns to New Mexico after fighting in World War 2. Momaday explores Abel’s war trauma by showing his inability to reconnect with reservation life and ritual. Yet after leaving New Mexico, Abel also finds it impossible to cope with urban living and its social norms.

Abel’s profound sense of alienation and search for identity is a theme that carries through other Native American Renaissance–era works, such as Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, and Joy Harjo’s She Had Some Horses. Together these writers had an immense impact on the direction and popularity of Native writing.

However, the term “Native American Renaissance” is in itself problematic. As critics have pointed out, the phrase implies a dearth of Native writers and writings before the 1960s, which is simply not true. Also, many of the writers included in the Renaissance have continued working into the present day, shifting their styles and careers beyond their initial moment of fame. Despite the controversial terminology, the 1960s Renaissance marks a significant and powerful turning point in contemporary Native writing.

In many ways, the authors associated with the IAIA challenge well-worn assumptions about what Native writing can be. For example, in her memoir Heart Berries, Terese Marie Mailhot gives a direct and unflinching account of her mental illness and institutionalization, a topic that is not frequently discussed in Native literature. Her prose rockets across the page, experimenting and pushing the bounds of the memoir genre. Likewise, Tommy Orange’s There There experiments with multiple narrative voices to show Native life in Oakland, California. Orange deliberately picked an urban setting for his debut novel, stating that “70 percent of Native people in the whole country are living in cities. And to not have had any representation of that story was pretty mind-blowing to me.”

Mailhot and Orange’s success have solidified the literary community and reputation of the IAIA. Undoubtedly, the Institute will continue to be a potent source for innovative and exciting Native writers.

In many ways, the authors associated with the IAIA challenge well-worn assumptions about what Native writing can be. For example, in her memoir Heart Berries, Terese Marie Mailhot gives a direct and unflinching account of her mental illness and institutionalization, a topic that is not frequently discussed in Native literature. Her prose rockets across the page, experimenting and pushing the bounds of the memoir genre. Likewise, Tommy Orange’s There There experiments with multiple narrative voices to show Native life in Oakland, California. Orange deliberately picked an urban setting for his debut novel, stating that “70 percent of Native people in the whole country are living in cities. And to not have had any representation of that story was pretty mind-blowing to me.”

Mailhot and Orange’s success have solidified the literary community and reputation of the IAIA. Undoubtedly, the Institute will continue to be a potent source for innovative and exciting Native writers.

One of the most powerful aspects of Native SFF is how its writers respond to historical exclusion. These writers often root the science and fantasy elements of their works in tribal culture and myth, thus creating worlds in which Native experience is central, rather than ancillary or non-existent. For example, in Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild, the main protagonist’s search for her husband gets bound up in the story of the rogarou—a werewolf-like creature that haunts Métis communities, according to tribal legend. Or, in Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse, members of the Osage Nation lead a counterattack against AI robots that have already wiped out most of humanity. In these works, the narratives work to amplify and promulgate worlds based on Native experience. Writers such as Dimaline and Wilson not only counteract the erasure of Native people in SFF, but also create futures based upon their experiences and cultures.

However, the use of Native cultures in SFF is not without controversy. Recently, Rebecca Roanhorse has received sharp criticism over her use of Navajo cultural and religious beliefs. In Trail of Lightning, protagonist Maggie Hoskie, a Navajo monster-slayer, tries to survive in a post-apocalyptic North American continent. Throughout the novel, Navajo spiritual practices factor heavily in the chaos and mayhem that ensue. Roanhorse, who is not Navajo, has been accused of appropriating cultural beliefs of which she is not a part. The controversy has spotlighted how an author should use cultural references, and when those references can be off-limits. Despite the controversy surrounding Roanhorse, Native SFF is certainly changing the genre itself in a variety of important ways.

One of the most powerful aspects of Native SFF is how its writers respond to historical exclusion. These writers often root the science and fantasy elements of their works in tribal culture and myth, thus creating worlds in which Native experience is central, rather than ancillary or non-existent. For example, in Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild, the main protagonist’s search for her husband gets bound up in the story of the rogarou—a werewolf-like creature that haunts Métis communities, according to tribal legend. Or, in Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse, members of the Osage Nation lead a counterattack against AI robots that have already wiped out most of humanity. In these works, the narratives work to amplify and promulgate worlds based on Native experience. Writers such as Dimaline and Wilson not only counteract the erasure of Native people in SFF, but also create futures based upon their experiences and cultures.

However, the use of Native cultures in SFF is not without controversy. Recently, Rebecca Roanhorse has received sharp criticism over her use of Navajo cultural and religious beliefs. In Trail of Lightning, protagonist Maggie Hoskie, a Navajo monster-slayer, tries to survive in a post-apocalyptic North American continent. Throughout the novel, Navajo spiritual practices factor heavily in the chaos and mayhem that ensue. Roanhorse, who is not Navajo, has been accused of appropriating cultural beliefs of which she is not a part. The controversy has spotlighted how an author should use cultural references, and when those references can be off-limits. Despite the controversy surrounding Roanhorse, Native SFF is certainly changing the genre itself in a variety of important ways.

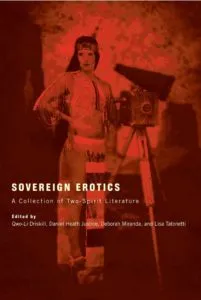

It is important to recognize that “Two-Spirit” is not a monolithic category. Different Native groups have a variety of understandings and social contexts under which to understand Two-Spirit, as well as LGBTQ+ identity. An excellent place to start reading is the anthology, Sovereign Erotics: A Collection of Two-Spirit Literature. This landmark collection of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, shows the diversity and brilliance of Native LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirit writing. It contains established writers such as Paula Gunn Allen and Maurice Kenny, as well as newer heavyweights including the poet and scholar Qwo-Li Driskell. Driskell’s poem, “Love Poem, After Arizona,” perfectly showcases the strong inclination towards decolonization in Two-Spirit literature. That, and hir lines are romantic, tender, and beautiful:

We are two mixed-blood boys

and know empires are never gentle

Take off your Mexica mask

so I can see your beloved

Nahua face

remove your wooden shield

so I can kiss your

Apache sternum

taste in your sweat

the iron of Spain

that never conquered us

I know, right?! After checking out Sovereign Erotics, I would recommend reading Ma-Nee Chacaby’s harrowing and moving memoir, A Two-Spirit Journey. If you are looking for fantasy that explores gender and sexuality in a Native context, take a look at Daniel Heath Justice’s epic trilogy, The Way of Thorn and Thunder: The Kynship Chronicles. Finally, if poetry is your thing, check out Gregory Scofield’s Love Medicine and One Song. In many ways, Two-Spirit writing captures the depth and diversity in contemporary Native literature. It celebrates and bears witness to what could not be erased.

It is important to recognize that “Two-Spirit” is not a monolithic category. Different Native groups have a variety of understandings and social contexts under which to understand Two-Spirit, as well as LGBTQ+ identity. An excellent place to start reading is the anthology, Sovereign Erotics: A Collection of Two-Spirit Literature. This landmark collection of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, shows the diversity and brilliance of Native LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirit writing. It contains established writers such as Paula Gunn Allen and Maurice Kenny, as well as newer heavyweights including the poet and scholar Qwo-Li Driskell. Driskell’s poem, “Love Poem, After Arizona,” perfectly showcases the strong inclination towards decolonization in Two-Spirit literature. That, and hir lines are romantic, tender, and beautiful:

We are two mixed-blood boys

and know empires are never gentle

Take off your Mexica mask

so I can see your beloved

Nahua face

remove your wooden shield

so I can kiss your

Apache sternum

taste in your sweat

the iron of Spain

that never conquered us

I know, right?! After checking out Sovereign Erotics, I would recommend reading Ma-Nee Chacaby’s harrowing and moving memoir, A Two-Spirit Journey. If you are looking for fantasy that explores gender and sexuality in a Native context, take a look at Daniel Heath Justice’s epic trilogy, The Way of Thorn and Thunder: The Kynship Chronicles. Finally, if poetry is your thing, check out Gregory Scofield’s Love Medicine and One Song. In many ways, Two-Spirit writing captures the depth and diversity in contemporary Native literature. It celebrates and bears witness to what could not be erased.

Want to continue reading about Native literature? Check out the excellent work done by my fellow Rioters here.

The “Native American Renaissance”

Coined in the mid-1980s by Kenneth Lincoln, the phrase “Native American Renaissance” refers to Native writers who gained a national audience starting in the 1960s. Many of these authors and poets are still active today, such as Leslie Marmon Silko, Louise Erdrich, Joy Harjo, and Simon Ortiz. According to Lincoln, Renaissance works share a number of things in common. They focus on ritual and reservation experience, as well as the difficulties of living outside of the reservation while holding onto tradition. In particular, N. Scott Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning House Made of Dawn changed the landscape of Native writing. Momaday’s novel influenced a younger generation of writers, providing a new aesthetic for detailing and describing facets of Native life. In the novel, the protagonist, Abel, returns to New Mexico after fighting in World War 2. Momaday explores Abel’s war trauma by showing his inability to reconnect with reservation life and ritual. Yet after leaving New Mexico, Abel also finds it impossible to cope with urban living and its social norms.

Abel’s profound sense of alienation and search for identity is a theme that carries through other Native American Renaissance–era works, such as Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, and Joy Harjo’s She Had Some Horses. Together these writers had an immense impact on the direction and popularity of Native writing.

However, the term “Native American Renaissance” is in itself problematic. As critics have pointed out, the phrase implies a dearth of Native writers and writings before the 1960s, which is simply not true. Also, many of the writers included in the Renaissance have continued working into the present day, shifting their styles and careers beyond their initial moment of fame. Despite the controversial terminology, the 1960s Renaissance marks a significant and powerful turning point in contemporary Native writing.

In particular, N. Scott Momaday’s Pulitzer Prize-winning House Made of Dawn changed the landscape of Native writing. Momaday’s novel influenced a younger generation of writers, providing a new aesthetic for detailing and describing facets of Native life. In the novel, the protagonist, Abel, returns to New Mexico after fighting in World War 2. Momaday explores Abel’s war trauma by showing his inability to reconnect with reservation life and ritual. Yet after leaving New Mexico, Abel also finds it impossible to cope with urban living and its social norms.

Abel’s profound sense of alienation and search for identity is a theme that carries through other Native American Renaissance–era works, such as Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Louise Erdrich’s Love Medicine, and Joy Harjo’s She Had Some Horses. Together these writers had an immense impact on the direction and popularity of Native writing.

However, the term “Native American Renaissance” is in itself problematic. As critics have pointed out, the phrase implies a dearth of Native writers and writings before the 1960s, which is simply not true. Also, many of the writers included in the Renaissance have continued working into the present day, shifting their styles and careers beyond their initial moment of fame. Despite the controversial terminology, the 1960s Renaissance marks a significant and powerful turning point in contemporary Native writing.

The Institute of American Indian Arts

Founded in 1962, the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) is a major cultural force in contemporary Native writing. As stated on its admissions page, it is the only fine arts school in the world to offer a 4-year program focused upon Native and First Nations art. Additionally, the IAIA has graduated writers and poets who are transforming the style and content of contemporary Native literature. Among these writers are Terese Marie Mailhot, Tommy Orange, Layli Long Soldier, and Jake Skeets. In many ways, the authors associated with the IAIA challenge well-worn assumptions about what Native writing can be. For example, in her memoir Heart Berries, Terese Marie Mailhot gives a direct and unflinching account of her mental illness and institutionalization, a topic that is not frequently discussed in Native literature. Her prose rockets across the page, experimenting and pushing the bounds of the memoir genre. Likewise, Tommy Orange’s There There experiments with multiple narrative voices to show Native life in Oakland, California. Orange deliberately picked an urban setting for his debut novel, stating that “70 percent of Native people in the whole country are living in cities. And to not have had any representation of that story was pretty mind-blowing to me.”

Mailhot and Orange’s success have solidified the literary community and reputation of the IAIA. Undoubtedly, the Institute will continue to be a potent source for innovative and exciting Native writers.

In many ways, the authors associated with the IAIA challenge well-worn assumptions about what Native writing can be. For example, in her memoir Heart Berries, Terese Marie Mailhot gives a direct and unflinching account of her mental illness and institutionalization, a topic that is not frequently discussed in Native literature. Her prose rockets across the page, experimenting and pushing the bounds of the memoir genre. Likewise, Tommy Orange’s There There experiments with multiple narrative voices to show Native life in Oakland, California. Orange deliberately picked an urban setting for his debut novel, stating that “70 percent of Native people in the whole country are living in cities. And to not have had any representation of that story was pretty mind-blowing to me.”

Mailhot and Orange’s success have solidified the literary community and reputation of the IAIA. Undoubtedly, the Institute will continue to be a potent source for innovative and exciting Native writers.

Native Science Fiction & Fantasy

Historically, mainstream science fiction and fantasy has had a big problem with diversity and representation of non-white characters. In her brilliant essay, “How Long ‘Til Black Future Month?”, N.K. Jemisin writes that the predominant whiteness lurking in SFF is due to “conscious choices on the part of the genre’s gatekeepers,” amounting to “deliberate, ahistorical, scientifically nonsensical, exclusion.” This exclusion of both writers and characters of color in the genre has been substantially challenged in the 21st century. Native SFF has been gaining a larger and more public readership, and consequently changing the perception of contemporary Native literature. One of the most powerful aspects of Native SFF is how its writers respond to historical exclusion. These writers often root the science and fantasy elements of their works in tribal culture and myth, thus creating worlds in which Native experience is central, rather than ancillary or non-existent. For example, in Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild, the main protagonist’s search for her husband gets bound up in the story of the rogarou—a werewolf-like creature that haunts Métis communities, according to tribal legend. Or, in Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse, members of the Osage Nation lead a counterattack against AI robots that have already wiped out most of humanity. In these works, the narratives work to amplify and promulgate worlds based on Native experience. Writers such as Dimaline and Wilson not only counteract the erasure of Native people in SFF, but also create futures based upon their experiences and cultures.

However, the use of Native cultures in SFF is not without controversy. Recently, Rebecca Roanhorse has received sharp criticism over her use of Navajo cultural and religious beliefs. In Trail of Lightning, protagonist Maggie Hoskie, a Navajo monster-slayer, tries to survive in a post-apocalyptic North American continent. Throughout the novel, Navajo spiritual practices factor heavily in the chaos and mayhem that ensue. Roanhorse, who is not Navajo, has been accused of appropriating cultural beliefs of which she is not a part. The controversy has spotlighted how an author should use cultural references, and when those references can be off-limits. Despite the controversy surrounding Roanhorse, Native SFF is certainly changing the genre itself in a variety of important ways.

One of the most powerful aspects of Native SFF is how its writers respond to historical exclusion. These writers often root the science and fantasy elements of their works in tribal culture and myth, thus creating worlds in which Native experience is central, rather than ancillary or non-existent. For example, in Cherie Dimaline’s Empire of Wild, the main protagonist’s search for her husband gets bound up in the story of the rogarou—a werewolf-like creature that haunts Métis communities, according to tribal legend. Or, in Daniel H. Wilson’s Robopocalypse, members of the Osage Nation lead a counterattack against AI robots that have already wiped out most of humanity. In these works, the narratives work to amplify and promulgate worlds based on Native experience. Writers such as Dimaline and Wilson not only counteract the erasure of Native people in SFF, but also create futures based upon their experiences and cultures.

However, the use of Native cultures in SFF is not without controversy. Recently, Rebecca Roanhorse has received sharp criticism over her use of Navajo cultural and religious beliefs. In Trail of Lightning, protagonist Maggie Hoskie, a Navajo monster-slayer, tries to survive in a post-apocalyptic North American continent. Throughout the novel, Navajo spiritual practices factor heavily in the chaos and mayhem that ensue. Roanhorse, who is not Navajo, has been accused of appropriating cultural beliefs of which she is not a part. The controversy has spotlighted how an author should use cultural references, and when those references can be off-limits. Despite the controversy surrounding Roanhorse, Native SFF is certainly changing the genre itself in a variety of important ways.

Two-Spirit & LGBtQ+ Native Writing

In the last few decades, Native literature by LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirit writers has gained more prominence and recognition. Well into the 20th century, Native writers who identified as LGBTQ+ or Two-Spirit were not only marginalized like their non-Native counterparts, but also suffered historical erasure through European colonization and attitudes towards sexual identity. Thus, identifying as Two-Spirit is often seen as an act of decolonization. Two-Spirit individuals frequently identify as third or fourth gender, thereby rejecting Western sexual mores and binary gender norms. It is important to recognize that “Two-Spirit” is not a monolithic category. Different Native groups have a variety of understandings and social contexts under which to understand Two-Spirit, as well as LGBTQ+ identity. An excellent place to start reading is the anthology, Sovereign Erotics: A Collection of Two-Spirit Literature. This landmark collection of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, shows the diversity and brilliance of Native LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirit writing. It contains established writers such as Paula Gunn Allen and Maurice Kenny, as well as newer heavyweights including the poet and scholar Qwo-Li Driskell. Driskell’s poem, “Love Poem, After Arizona,” perfectly showcases the strong inclination towards decolonization in Two-Spirit literature. That, and hir lines are romantic, tender, and beautiful:

We are two mixed-blood boys

and know empires are never gentle

Take off your Mexica mask

so I can see your beloved

Nahua face

remove your wooden shield

so I can kiss your

Apache sternum

taste in your sweat

the iron of Spain

that never conquered us

I know, right?! After checking out Sovereign Erotics, I would recommend reading Ma-Nee Chacaby’s harrowing and moving memoir, A Two-Spirit Journey. If you are looking for fantasy that explores gender and sexuality in a Native context, take a look at Daniel Heath Justice’s epic trilogy, The Way of Thorn and Thunder: The Kynship Chronicles. Finally, if poetry is your thing, check out Gregory Scofield’s Love Medicine and One Song. In many ways, Two-Spirit writing captures the depth and diversity in contemporary Native literature. It celebrates and bears witness to what could not be erased.

It is important to recognize that “Two-Spirit” is not a monolithic category. Different Native groups have a variety of understandings and social contexts under which to understand Two-Spirit, as well as LGBTQ+ identity. An excellent place to start reading is the anthology, Sovereign Erotics: A Collection of Two-Spirit Literature. This landmark collection of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, shows the diversity and brilliance of Native LGBTQ+ and Two-Spirit writing. It contains established writers such as Paula Gunn Allen and Maurice Kenny, as well as newer heavyweights including the poet and scholar Qwo-Li Driskell. Driskell’s poem, “Love Poem, After Arizona,” perfectly showcases the strong inclination towards decolonization in Two-Spirit literature. That, and hir lines are romantic, tender, and beautiful:

We are two mixed-blood boys

and know empires are never gentle

Take off your Mexica mask

so I can see your beloved

Nahua face

remove your wooden shield

so I can kiss your

Apache sternum

taste in your sweat

the iron of Spain

that never conquered us

I know, right?! After checking out Sovereign Erotics, I would recommend reading Ma-Nee Chacaby’s harrowing and moving memoir, A Two-Spirit Journey. If you are looking for fantasy that explores gender and sexuality in a Native context, take a look at Daniel Heath Justice’s epic trilogy, The Way of Thorn and Thunder: The Kynship Chronicles. Finally, if poetry is your thing, check out Gregory Scofield’s Love Medicine and One Song. In many ways, Two-Spirit writing captures the depth and diversity in contemporary Native literature. It celebrates and bears witness to what could not be erased.

Want to continue reading about Native literature? Check out the excellent work done by my fellow Rioters here.