Reading Through Difficult Times: Books and Their Readers in 1918–1920

The human race has been dealing with violent outbreaks of contagious diseases for the entirety of its existence. Before there was COVID-19, there was the Influenza epidemic, sometimes known as the Spanish Flu (named so, ironically, because the Spanish media, unfettered by wartime censorship, actually reported the outbreak ), and before that there were several deadly plague outbreaks. The influenza epidemic, despite killing at least 50 million people worldwide, has been largely absent from collective memory. While the diseases themselves are very different, a foray into the history of this pandemic, in context of the overwhelming and unprecedented crisis that we are currently facing, reveals striking similarities in institutional and individual responses between then and now.

From fake news and conspiracy theories about the origin of the disease, miracle cures to resistance to mask wearing, the influenza outbreak had seen it all. But despite the far-reaching impact of the pandemic, personal and scholastic accounts of the outbreak are surprisingly few. In her essay On Being Ill, Virginia Woolf says about illness, and the reason for the dearth of its representation in literature:

To look these things squarely in the face would need the courage of a lion tamer; a robust philosophy; a reason rooted in the bowels of the earth. Short of these, this monster, the body, this miracle, its pain, will soon make us taper into mysticism, or rise, with rapid beats of the wings, into the raptures of transcendentalism.

Virginia Woolf, On Being Ill

This statement is probably most applicable to the influenza epidemic, a disease which struck at a time when great advances in medical sciences had made medical professionals confident about their ability to treat, or manage, the spread of infectious diseases. The outbreak was also contemporaneous with the last leg of the First World War, a conflict that had caused widespread devastation, shaken political and social institutions to their core and had already overwhelmed the public psyche with news, dread, nationalism, and calls for help.

While pandemic survivors were largely reticent about the flu once it was over, many of them maintained diaries, wrote letters and composed poetry and parodies during the pandemic. From these personal testimonies, a sense of acute loneliness and isolation emerges as people are deprived of the social spaces that were supporting them through already difficult times. Without digital connectivity that has helped people stay in touch through the recent lockdowns, many turned to books for comfort and occupation.

Libraries in the Pandemic

Most public libraries were closed during the outbreak, with provisions to return borrowed books. Fines were not charged for books that could not be returned within this period. Whether or not books that had come into contact with influenza patients needed to be destroyed was seriously considered. Some libraries even went as far as to destroy stacks of “infected” books. Libraries that remained open saw surges in circulation. As an article in the Los Angeles Times reports, there was a massive increase in the number of books that were borrowed from the public libraries. History books and books on war appear to have been most popular, and bookstores registered a rise in magazine sales. Columnists like Dolly Dalrymple of the Birmingham Age-Herald (problematic philosophy and assumed persona notwithstanding) recommended books for quarantine reading, much like book blogs and magazines today.

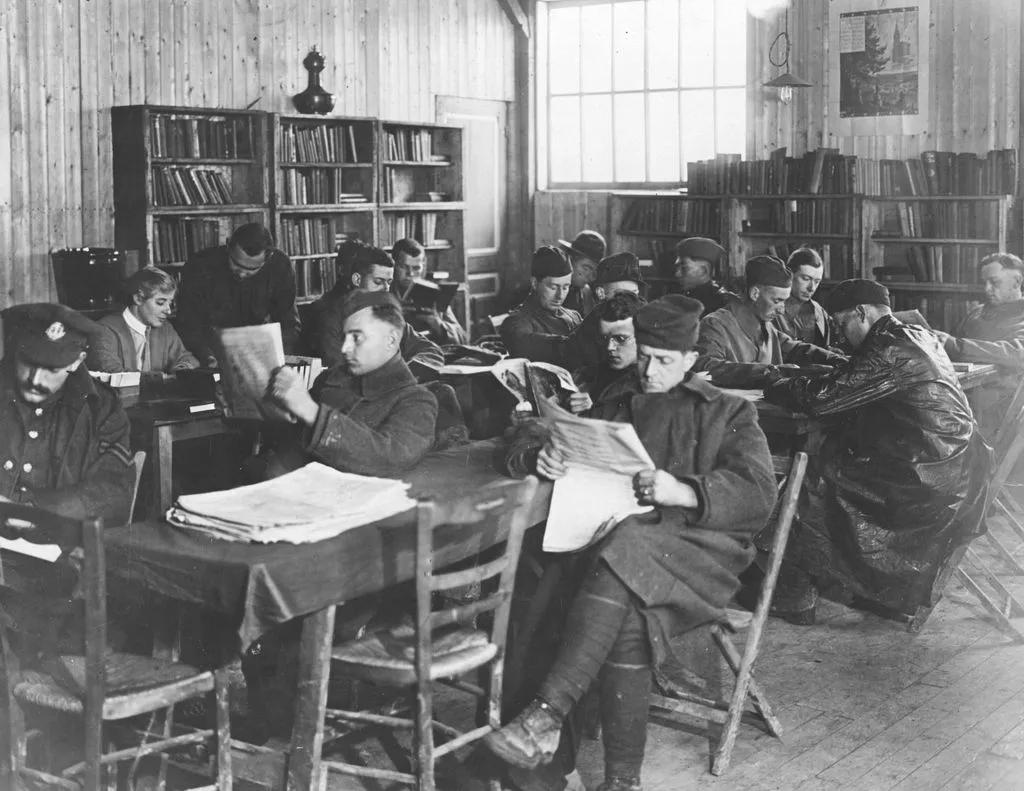

Wartime Reading

Discussion of any aspect of the history of the period without placing it in context of the conflict that singlehandedly shaped public discourse during the time – the First World War – is incomplete. It is somewhat of a landmark in the global history of reading, for scholars believe that the idea of caregiving through literature, started taking concrete shape with The Red Cross and Order of St John War Library, established in Britain, brainchild of Helen Mary Gaskell. Calls for donating books for soldiers were published in newspapers, and the public responded with ready enthusiasm. There was a tremendous demand from soldiers, which even this unexpected enthusiasm had trouble keeping up with. Cheaper editions of popular books were in high demand, keeping the publishing industry afloat through paper shortages and loss of staff to the war effort. The hospital libraries set up under this initiative provided crucial emotional support to both influenza patients and those wounded in war.

When America entered the war in 1917–1918, a similar project was undertaken by the American Library Association (ALA). The ALA archives are a tribute to the impact that camp and field libraries had on soldiers struggling with uncertainty and sickness. While the official ALA publications tried to highlight the esoteric, literary or technical titles requested by the productive American soldier, some heartbreakingly honest accounts snuck in. A librarian at an army camp in New Mexico reports how the young recruits, still in their teens, refuse to read anything but young adult literature that she calls “boys’ books,” and another war camp librarian recounts how a shy young soldier came in asking for books on how to write love letters. Civilians’ concerns for the young men fighting in the war were expressed through the handmade scrapbooks that British volunteers compiled to be sent to the men at the front, meant especially for those too weak to read, and American school children compiled joke books for soldiers.

Writers’ Reading

The post–World War I world saw a revolution in literature, with the ushering in of modernism through the writings of poets and authors who did not shy away from experimentation and honesty. Many of these writers were alive in 1918–1920, reading books that would later influence their writing.

Virginia Woolf suffered several influenza attacks, and muses about reading when sick in On Being Ill. She talks about the relationship between how we perceive the things that we read and the state of our health, in a perceptive discourse at a time when the nature of the relationship between the mind and the body had not been established in popular culture. Woolf’s personal experiences of reading through influenza can be found in her letters and diaries. In a 1918 letter, she writes about the joy of reading Shakespeare in the garden after a bout of influenza rendered her unable to read for a few days. Another encounter with the disease at the end of 1919 sees her ploughing through enormous tomes. She reads the memoirs of Charles Greville and two volumes of the biography of Samuel Butler by Henry Festing Jones, books that she considers “superbly fit for illness”.

Some of the most celebrated writing about the disillusionment of the war came from the English war poets Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. Owen relied heavily on poetry as he had to face the horrors of war. He read Keats, Yeats, Housman, Tagore, Shelly and Swinburne, carrying a volume of Swinburne in his kit when he was killed in the battlefields of France, mere days before the armistice. Owen’s friendship with Sassoon is one of the most iconic friendships in literary history, ignited at the Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh. The two poets influenced each other’s reading and writing till Owen’s death in 1918. At the hospital, Sassoon was reading Under Fire by Henri Barbusse, admiring it for its depiction of war. He later lent the book to Owen. Sassoon was an ardent admirer of Thomas Hardy, and introduced Owen to his poetry. They also read and critiqued each other’s poems. In a diary entry, Sassoon talks about a manuscript of poems by another famous war poet, Robert Graves.

In the United States, the poet E.E. Cummings was sitting out an influenza quarantine as a conscript at camp Denver, Massachusetts. He spent his days in an enclosure with several other enlisted men, passing his time reading the novels of James Joyce and articles on literary criticism.

Bestsellers and Classics

Publishers Weekly has been releasing bestsellers lists for fiction and nonfiction in the U.S. since the early 1900s. The lists were compiled using sales data for hardcover titles from bookstores in major cities (as opposed to publishers). This method has both pros and cons, and the accuracy of the lists can be questioned. However, we can safely assume that they provide a fair picture of the kind of books that were popular with the average American reader. In 1918–1920, works that are later recognized as classics often did not become bestsellers in their year of publication, and for each of the three years between 1918–1920, here is a round up of the general theme of the books on the bestseller list, as well as some of the titles written in that year that would later be established as literary classics.

1918: Bestsellers

The western appears to have been popular in this period, and Zane Grey, a master of the genre, appears in the fiction bestseller lists of all three years. The U.P. Trail, a classic western about the construction of the Union-Pacific railroad, tops the list for 1918. Books about the war are already popular – eight out of the ten fiction titles on the list have war-related themes. The books are plot driven, mostly romance, adventure, or humour, that would have provided readers some respite from the greater horrors of war by helping them immerse themselves in a specific, often heroic, story. Of the best-selling books from this year, The Tree of Heaven by May Sinclair and The Amazing Interlude by Mary Roberts Rinehart are remarkable for their plot and the spunky female protagonists.

1918: Classics

In 1918, Willa Cather wrote My Ántonia, an early masterpiece also set in the American West. The second Pulitzer prize for fiction in 1919 was awarded to The Magnificent Ambersons, Booth Tarkington’s 1918 novel about the decline of an old aristocratic family in the face of rapid social and economic change.

1919: Bestsellers

The 1919 bestseller list features two durable novels that also achieved critical acclaim – The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse by Spanish author Vicente Blasco Ibáñez and The Arrow of Gold by Joseph Conrad. War novels continue to dominate, and like the popular books from 1918, these are plot-driven stories that largely conform to the popular narrative and prejudices of the war.

1919: Classics

In 1919, Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson was published. Written as a series of interconnected short stories that are set in the same fictional small town in Ohio, the book is hailed as a precursor of later modernist works for its structure and style. The same year, Virginia Woolf published Night and Day, her incisive treatise on love, marriage and women’s independence. Another celebrated novel published this year is Somerset Maugham’s The Moon and Sixpence. It is interesting to note that while popular fiction abounded with war novels and the poignant poetry of the war poets was already being published, not many of the classic works of fiction written at this time deal directly with the war. It would appear that for an in-depth exploration of the complexities of the war (or the influenza pandemic for that matter) in the longer literary format, some distance was necessary.

1920: Bestsellers

The war fails to hold public interest much longer, and the bestseller list for 1920 sees a drastic drop in war novels, with none of the ten novels listed dealing directly with the war. Zane Grey tops the list again, with The Man from the Forest. The bestsellers are conventional thrillers, adventures or romances.

1920: Classics

In 1920, The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton and Main Street by Sinclair Lewis were published, both contenders for the Pulitzer prize in fiction, which ultimately went to Edith Wharton because of the political content of Main Street. Three Soldiers by John Doss Passos was published this year – one of the first realist war novels from the First World War. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s This Side of Paradise, published in 1920, is another well received and enduring classic. Despite being set during and after the First World War, the book does not explicitly discuss the experiences of war or the pandemic. Another important book published in 1920, a reference point for the study of sexuality in fiction, is D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love.

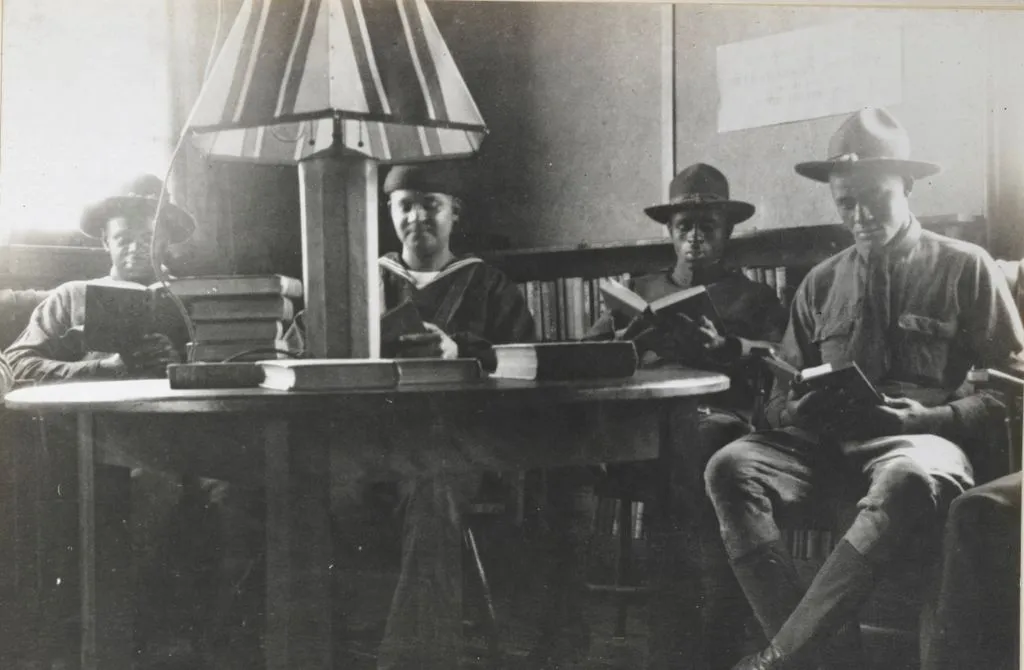

African American Literature

The armies of the First World War also comprised of people of color who participated in and were killed by the war, and they were disproportionately affected by the influenza epidemic, despite being subject to discrimination by governments at home. The contribution of these people and their experiences in these turbulent times – be it African Americans in the USA or the colonial subjects of the British Empire, are woefully under-represented in popular culture. From the discussion of mainstream bestsellers and classics, it is almost impossible to comment about their literary lives. But even a cursory study of the literature that these communities produced before and after the war and the pandemic would assure one that their reading lives were far from dormant.

By the late 19th century, African American poets like Paul Laurence Dunbar and Albery Allson Whitman were producing seminal works of poetry. Novelists like Frances Harper, Sutton E. Griggs, and Charles W. Chesnutt were using fiction to talk about racial injustice and providing a powerful counterpoint against the popular white rhetoric. 1919 saw a series of incidents of racial violence, later termed Red Summer. The worsening of the condition of African Americans in the years following the war gave rise to one of the most iconic literary movements of all times, the Harlem Renaissance of the first half of the twentieth century.

1918–1920 was a difficult time in human history. Yet the experiences of this time were soon overshadowed in public memory by the turbulence of the interwar years and eventually the Second World War. The limited evidence that we have of the history of reading from the period underscores the relationship between popular sentiment, literature, history, and socio-political changes. It goes to show how for years human beings have relied on the power of the written word for comfort as well as intellectual stimulation, and a more detailed analysis of what we liked to read as a society would reveal our worst vices and strongest virtues. In context of the current crisis, it is also a timely reminder for us to keep our reading diverse and our prejudices to a minimum.