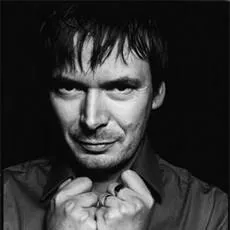

Blood and Beer – A Pint With Ian Rankin

A charcoal Monday in Edinburgh. January. Lunchtime. Rain. The Oxford Bar. Ian Rankin is opening letters

“Look at this one,” he says, putting down his pint. He reads each line of the address aloud: “To Ian Rankin. Edinburgh. Scotland. Try the Oxford Bar.” It has been many weeks since Rankin last collected his mail. A UK tour to promote his latest novel, Standing In Another Man’s Grave, has kept him from supping his favoured drink (Deuchars IPA for anyone who is buying) in his favoured haunt.

The scattergun missives from fans have built up. He opens another. As well as a letter to the crime writer, it contains an envelope for JK Rowling, Rankin’s friend and, until recently, neighbour. It never leaves the bar.

A gaggle of revellers who seem to have confused Monday afternoon for Saturday night burst in from the damp street outside. They are from Fife, Rankin’s home, across the Firth of Forth. He ducks his head, orders a round of drinks, and we retire to the sparse back room.

Rankin is the UK’s best-selling crime writer. His Edinburgh-set novels featuring the uncompromising and brilliant Inspector Rebus have gained him a worldwide following. Despite retiring Rebus in 2007’s Exit Music, the good inspector is back for an eighteenth outing in Standing In Another Man’s Grave.

Today, however, Rankin is catching his breath. One book finished, another due later this year. One book tour completed, another about to begin. Eleven US cities in 12 days.

His novels might be grounded in Scotland’s dark, loamy soil, but Rankin’s writing has transatlantic roots. Before he heads to the US to renew the relationship, he shares with Book Riot his love of American crime fiction, how the Brits do murder differently, how Isaac Hayes set him on his road to literary fame, and what happens when James Ellroy signs your book.

On why US crime fiction is better than its English counterpart

“Like a number of British crime writers of my generation I was influenced by American films, American TV and American writers rather than Agatha Christie and PD James, the classical English school of bloodless detective fiction. That is all about intelligent people up against other intelligent people, usually involving obscure poisons and blows to the back of the head rather than guns and femme fatales.

“Agatha Christie meant nothing to me. I tried when I was a kid but couldn’t get into it. It was all about a polite, gentile English village into which an act of violence would erupt, but clever middle-class and upper-middle class people would use their wits to bring stability back to the village. I just thought, what? I was living in a town with lots of skin heads in Doc Martins, football hooligans and unemployment.

“The American stuff was more glamorous. They were in a big city, driving fast cars, they carried guns. My dad and I were suckers for all the American cop shows, whether it was Ironside or Columbo. A lot of that seeped in.”

On how the sex machine to all chicks set him on his way

“The first crime fiction I ever read would have been Shaft. When I was 11 I bought the single, by Isaac Hayes. I thought it was fantastic. I didn’t realise it was the theme for a movie, which I couldn’t see anyway because it had an X certificate. I was 11. So I went and bought the book. They wouldn’t let you into the cinema to see it, but you were allowed to buy the book. So I bought the books of The Godfather and The French Connection. But the first was Shaft. It was years until I realised it was written by a white guy, Ernest Tidyman. But I love it. It was very exotic. I was living in a tiny coal mining town in Scotland and here was this whole other world.”

On writing crime novels before actually reading one

“I’d written the first Rebus novel before I started reading crime fiction. When the book came out it was classified as a crime novel by the media and book sellers. I thought I was updating Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, but because I’d written about a cop and crime it was a mystery novel. I thought I’d better start reading the company I was keeping.

Having grown up not having read the traditional English crime stories, when I started reading crime fiction, it was the Americans I started going to. My influences were the likes of Lawrence Block. I read all of them. They were the first American crime novels I got into.”

On why a private investigator in UK crime fiction is impossible

“There can’t be. We don’t believe in them as real people. We don’t know them. The private eye is an American archetype. He is like the lone gunman who comes into town and brings order. He is the outsider. We don’t have that in our psyche, in our tradition of writing.

“When I started writing the Rebus novels I was conscious this guy was operating almost like a private eye. He is a maverick. He is much more suited to the life of a PI than a cop. He likes to run his own investigation in his own way. I had to find a way of making that realistic in a police context.

“He shouldn’t be a cop because he doesn’t do the whole authority thing. He would have been kicked out on his arse long ago if he’d been a real cop.”

On how James Ellroy changed everything

“The first Ellroy I read was Blood On The Moon, which was turned into a film called Cop with James Woods. It was an early Ellory. I had a film tie-in version, so it had a picture of James Woods on the cover with a shotgun. I remember going up to Ellory, first time I met him, and asked him to sign it for me. He just drew a swastika on James Wood’s forehead and put a little speech bubble coming out of his mouth saying ‘I’m a weenie wagger’. I thought great, thanks man.

“But he influenced me big time. The language and the staccato rhythms. And the slang. That changed the way I wrote. Black and Blue [the eighth Rebus novel] was written in a completely different way. That was down to his influence.

“He wrote about real crimes and real criminals. When I realised I could do that that changed the Rebus novels. Before I thought if I’m writing fiction it has to be fictional. But Black and Blue was about a real crime, about Bible John. It was the first time I’d done that.”

On the Arthurian beauty of Raymond Chandler

“The opening of The Big Sleep is perfect. It is beautifully written. It gives you a lot of info about the psychology of the character. You don’t know who he is yet, but he is taking such care over getting dressed for a big meeting. And then at the end there is a slight joke that deflates it: “I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.” So you know he’s going to meet someone with a lot of money, you know he’s a PI, you know he’s quite successful as he has these good clothes that he wears.

“Chandler was a craftsman. He was a beautiful writer. He was educated at a good English school, at Dulwich College, at the same time as PG Woodhouse. He was brought up on the classics, speaking Latin. He knew what he was doing. He knew he was continuing the Grail Myth. Philip Marlowe was going to be a tarnished knight saving damsels in distress from dragons. He was going to be called Mallory originally, as in as in Sir Thomas Mallory [who popularised the Arthurian legends]. It’s all in there, which is lovely.

“The plot doesn’t make any sense though. But as soon as I read it, I loved it. The one-liners are great. And he was okay with having someone walk in with a gun if you’re stuck. It’s something British crime writers can’t do so much, but American crime writers can.”

On disagreeing with Dashiell Hammett

“I never really got on with Hammett. I loved The Thin Man. I just thought that was fantastic. But some of his plotting is just ludicrous. All the coincidences. All the stuff you also get in Conan Doyle. Come on. It needs to have some psychological realism. I get it in Chandler. I don’t get it so much in Hammett. I tried all of them. The Maltese Falcon is a great film. I wasn’t so enamoured with the book.”

On receiving writing advice from Elmore Leonard

“I met him once. I was in London to see him receive a Diamond Dagger award, a lifetime achievement, and this guy was walking towards me carrying one of my books. I told him, I wrote that. Turns out it was Elmore Leonard. It was hilarious. And weird.

“How was he? He tried to persuade me not to use adjectives and adverbs, but besides that, he was fine. He has these rules for writing, strip out as much as possible. But you can learn a lot about dialogue from him.”

On why James Lee Burke is the master

“The opening chapter of Black Cherry Blues, his first Dave Robicheaux novel, it is an absolute classic. If I was going to take a class on crime writing I would just give the students this chapter. It’s the perfect opening chapter of a book. Everything you need is in there – the characters, the situation, a suggestion of what might happen, what the theme might be – bang, in one short chapter.”

On finding success in the US

“It is difficult for British authors to break through in the States. Not many have done it. I’ve had meetings with agents and publishers who say, if you want to succeed in the States, set your book there, get an American hero. Like Lee Child or John Connolly. But I’m not interested in writing that kind of book. I want to write about the world that I know. When I’m writing I don’t think, what’s the lowest common denominator so I can sell to a worldwide audience. I’m writing for me. And for a circle of friends. If anyone gets it outside that circle, then great.

“The first people who bought them in the US were expat Scots, who wanted to read about the old country. Hopefully they then told their friends, who told their friends. A lot of my success has come about via word of mouth. People, librarians, saying check out this guy, he’ll tell you things about Scotland you never knew. If you’re expecting Greyfriar’s Bobby and Brigadoon, you’re in for a surprise.

“Scottish crime writing also comes from a different place. A lot of us have been influenced by American literature and movies, but also by Scottish ballads and quite dark Scottish texts, like The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and Jekyll and Hyde. A lot of gothic stuff. Just like Scandinavian crime fiction, it’s dark a lot of the year and it’s quite cold. You can imagine dark things happening here, behind thick stone walls.”

On the possibility of Rebus heading to the US

“Realistically? Not much chance. There might be opportunities only if a Scot was killed in America on holiday. Then someone from their local police force in Scotland might be sent across. Would you send Rebus? Probably not. He’s too much of a loose cannon.”

Ian Rankin will be appearing at the following events:

1/22: New York, NY- Barnes & Noble Upper East Side

1/24: Los Angeles, CA – Book Soup

1/25: Half Moon Bay, CA – Bay Book Company

1/26: Corte Madera, CA – Book Passage

1/27: Scottsdale, AZ – Poisoned Pen

1/28: Beaverton, OR – Powell’s

1/29: Seattle, WA – University Bookstore

1/30: Houston, TX – Murder By The Book

1/31: Chicago, IL – Anderson’s Bookshop Naperville

2/1: Milwaukee, WI – Boswell Books/Mystery One

2/2: Washington, DC – Politics & Prose